About Ben Graham

“My natural inclination, I believe, was always away from the material and towards the intellectual and even the spiritual side of life. But the difficult conditions of my childhood existence affected me…I became too conscious and respectful of money. I took it for granted that the primary mark of success in life lay in large earning and large spending.”

— Benjamin Graham

How Benjamin Graham Became a Wall Street Icon

“Buy not on optimism, but on arithmetic.”

—Benjamin Graham

Starting in 1928, Ben Graham and David Dodd taught value investing and security analysis at Columbia Business School. The class became hugely popular with investment professionals, in part because some bright students made profits by investing in the companies Ben Graham used to illustrate his points. In 1934, Benjamin Graham and his co-teacher David Dodd, published the 750-page tome titled Security Analysis, still considered a Wall Street Bible. Security analysis became a profession in its own right; today we call specialists in this field “financial analysts.” They carry on the Ben Graham method of using metrics to make smart investment decisions. Ben Graham’s innovations revolutionized stock valuation and banished the speculation of the early 20th century in favor of sound investing.

Security analysis enabled Ben Graham to use mathematical models to determine which stocks were likely to give the best returns with the least risk. He looked for stocks that were undervalued, that is, priced below what his calculations showed they were worth. He called this strategy “value investing.” To say that his strategy has caught on is a titanic understatement. Countless investors around the world call themselves value investors. They read Benjamin Graham’s books, calculate the intrinsic value of stocks, write blogs, and keep his ideas at the forefront of investment discourse.

As a finance professor, Ben Graham taught and mentored famed investors Warren Buffet, Sir John Templeton, Walter Schloss and Irving Kahn. His influence on business education persists to this day. The Columbia Business School offers courses in value investing at the Heilbrunn Center for Graham & Dodd Investing. Starting in 1956, Ben Graham taught security analysis, without pay, at UCLA’s Graduate School of Business Administration. Currently, the UCLA Economics Department offers a focus on investing and finance in the Benjamin Graham Value Investing Program.

“The most brilliant financial strategy consists of living well within one’s means.”

—Benjamin Graham

How Benjamin Graham Became an Inspirational Figure

Born in England in 1894, Benjamin Grossbaum (later named Benjamin Graham) came to America on a boat as a Jewish immigrant. After his father’s death left his family in financial hardship, Ben devoted himself to getting an excellent education in New York’s stellar public schools while taking after-school jobs to help his widowed mother make ends meet. He continued to work numerous jobs to help support his family while putting himself through college. His exceptional intelligence garnered notice at Columbia University: a dean recommended him for a position at the Wall Street firm where Ben launched his investment career in 1914. That same year, the family changed its name from Grossbaum to Graham to avoid anti-German sentiment and anti-Semitism. Starting in 1919, his “upward progress in Wall Street was rapid, even spectacular.” After growing up poor, Benjamin Graham not only achieved the American dream, but also joined the legions of immigrants who introduced groundbreaking ideas and made lasting contributions to American thought and culture.

The Limits of Wealth

No sooner had Ben Graham begun acquire to wealth than he discovered its limits. Money didn’t protect him from painful loss. Money didn’t make him happy. Having wealth didn’t help him to have a good marriage with his first wife Hazel, or to forge caring relationships with family members and friends.

“Through chances various, through all vicissitudes, we make our way… Aeneid”

— Epigraph of The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham

The reduced circumstances of his youth had crystallized Ben Graham’s conviction that he could only prove his worth by getting rich. He wrote in his Memoirs that he considered it discreditable when his wealthy colleague Bernard Baruch decided “to dedicate himself formally to making a lot more money, all for himself.” Unquestionably, Ben Graham had the skills to do the same. However, while he did go about building his own assets, he also gravitated toward the meaningful work of helping others find financial security: as a money manager and investment advisor, a teacher, and a writer.

Tragedy and its Aftermath

In 1954, shortly after he turned sixty, Ben Graham suffered a family tragedy. Never before must the limitations of amassing wealth for its own sake have seemed more glaring. Although he did not document his inner life in the aftermath of this loss, his subsequent actions suggest that its shock waves triggered deep introspection.

In 1956, when he was sixty-two, Ben Graham shuttered his Wall Street office. This marks the end of the legendary run that put him on the list of Forbes’ Top Five All-Time Fund Managers—a twenty year period where the fund he managed with partner Jerome Newman earned an estimated return of 21% annually. His retirement from investing at the peak of his powers demonstrated that he no longer believed that the mark of success lay in “large earning and large spending”—a stunning turnaround for a man of finance.

Key Insights

In one of the 1957 autobiographical vignettes noted in his Memoirs’ “Chronology,” Ben Graham set down some key insights, including the perception that he was “remote and inaccessible to others.”

“Why, since the end of his college years, had he admitted no one—man or woman—into a true intellectual and emotional intimacy? Why had he no pals, no chums?”

— Benjamin Graham

Many people, especially brilliant achievers like Ben, prefer not to see their own wounds. Ben Graham had the courage “to do hard things”—to acknowledge his pain, to identify his defenses against it, and to begin opening his heart.

Both this new self-awareness and the woman “from outre mer…entering his life and profoundly moving it” likely propelled him to make major changes in his life. However life-affirming these changes proved to be for Ben, there’s no denying that he hurt those he left behind.

Ben Graham’s Last Twenty Years

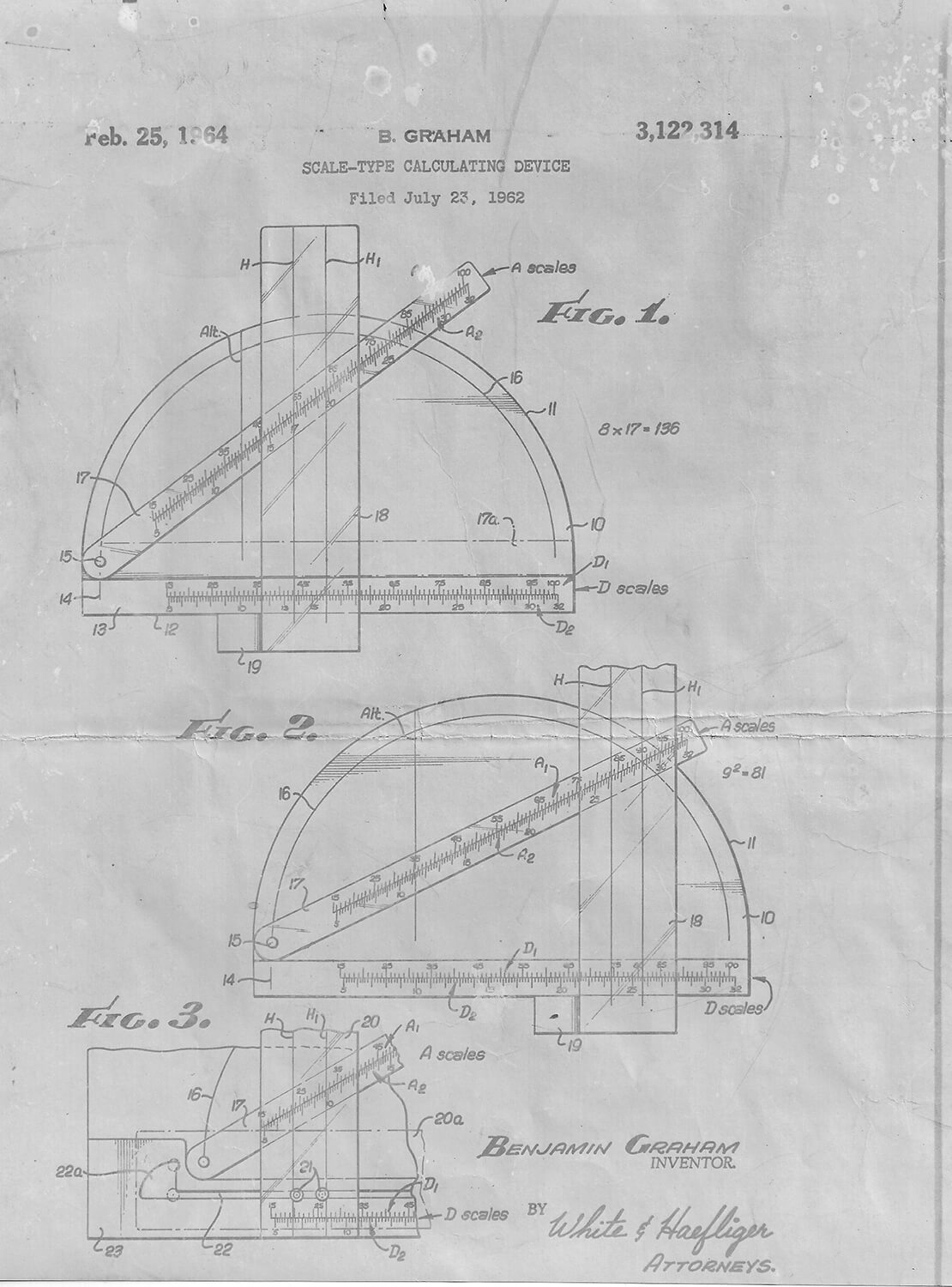

For the final twenty years of his life, Ben sought and found contentment in new ways. At last, he formed a stable and enduring relationship with a loving woman. He lived with “his precious Malou” in two small homes (modest places in upscale locales), spent sparingly, and translated the Iliad from the ancient Greek, his bobbing pen irresistible to his cat Minet. He tackled projects as various as designing a “Scale-Type Calculating Device” (which resembles a semi-circular slide rule) and, with his brother Victor, funding a memorial for their mother—a rebuilt church for a Black congregation in Bridgeport, Connecticut that had lost its place of worship in a fire.

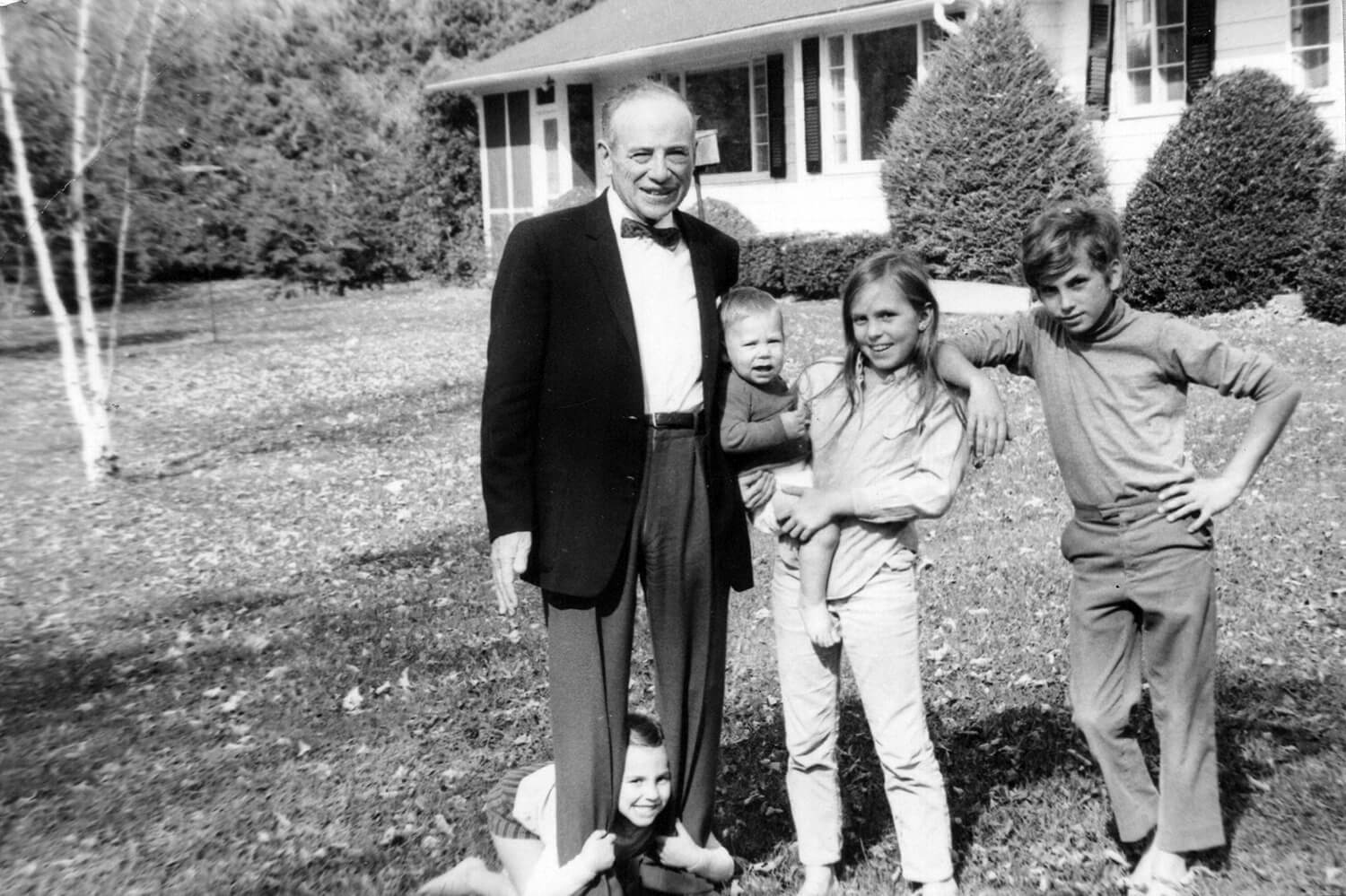

Ben Graham did not record for posterity how he came to terms with the loss he suffered in 1954, or, after some years, how he found acceptance and moved forward with changed priorities. As a child and young adult, I was privileged to witness his evolution. In the late ’50s and early ’60s, when my parents and I stayed with him and his wife Estelle in their stately Beverly Hills home, my gracious and lively Grandma Estey sat talking with us on their white shiny plastic-wrapped couch while Grandpa Ben retreated to a back room. By the late ’60s, my smiling Grandpa Ben was the one sitting beside me on his soft honey-yellow striped couch, engaging me in conversation.

Ben Graham didn’t just live differently than he had before; he was different. Friends quoted in Joe Carlen’s biography The Einstein of Money: The Life and Timeless Financial Wisdom of Benjamin Graham, agree that Ben changed: “Malou really helped him open up.” While his relationship with Malou was a big part of his transformation, it was his private soul-searching that enabled him to recognize what brought him joy and begin to heal the wounds he had carried since boyhood.

Grandparenting Years

Few would expect an inaccessible man, with a wall around his heart and three marital breakups behind him, to be amiable and welcoming toward family members in his “grandparenting” years. Certainly not this failed husband and often absent father, whom his third wife Estelle (as he quotes her in his Memoirs) called “humane, but not human.” I find it extraordinary that, late in life, Benjamin Graham forged a relationship so palpably affectionate that he and Malou shared their sparkling moments with others.

Fulfillment

This once remote man became present with those around him. He radiated friendliness and taught the art of happiness by example. He conveyed kindhearted acceptance to me, one of his grandchildren, and perhaps to other young family members. Rock by log by brick, he had dismantled the “breastwork” that once closed off his heart.

Ben Graham’s story offers wisdom about moving through loss and grief, staying hopeful, and never giving up the quest for fulfillment. When he set out to heal his wounded heart, he lit the way for others to heal. His example inspires us, not only to foster our own flourishing, but also the flourishing of future generations.