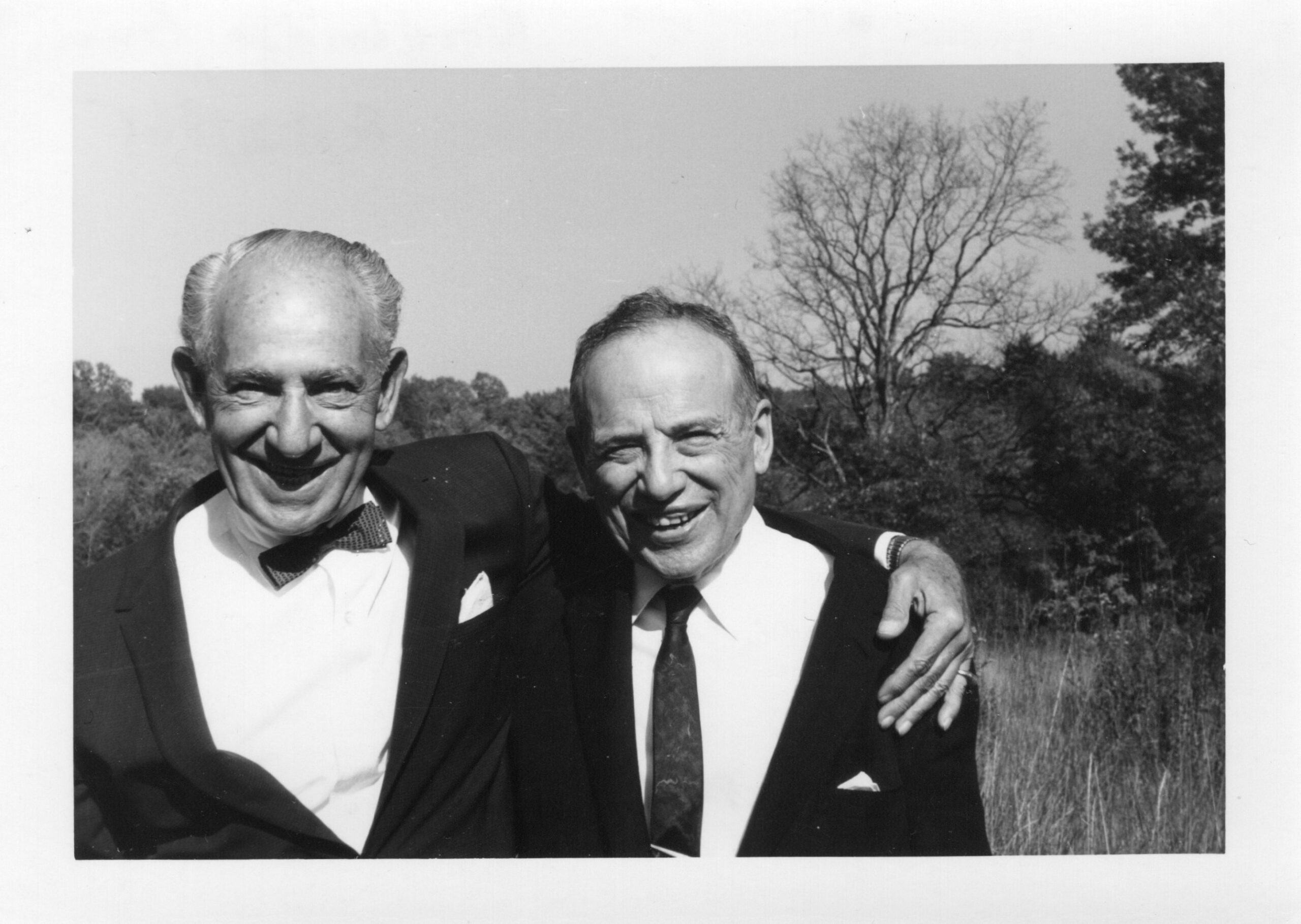

I never thought I’d be saying this, but I was wrong about Ben Graham’s mother. In my last post, I sat in judgement on my great-grandmother Dorothy Gesundheit Graham. I focused on the ways she was one of “those who loved him dearly [who] would so often wound him, with nonchalance.” Nonchalant—casually unconcerned, not going to the trouble to give comfort, or get up in time to see him off to school—summed up her mothering style. Even when I came to appreciate her for toughening his shell and teaching him how to survive hardship, I missed the point.

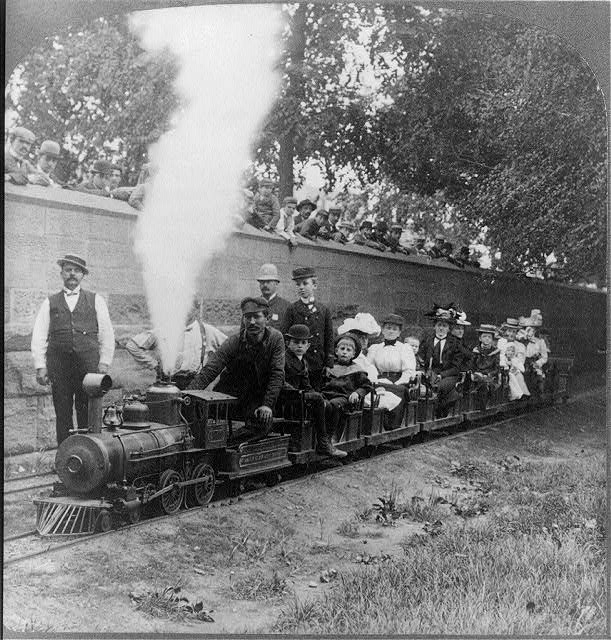

Dorothy gave Ben Graham a key motivating message that fueled his spectacular rise on Wall Street. Before I discovered that message, I joined Ben, age seven, and his brothers on an expedition to visit a miniature train.

The Joys of a Turn of the Century New York Childhood

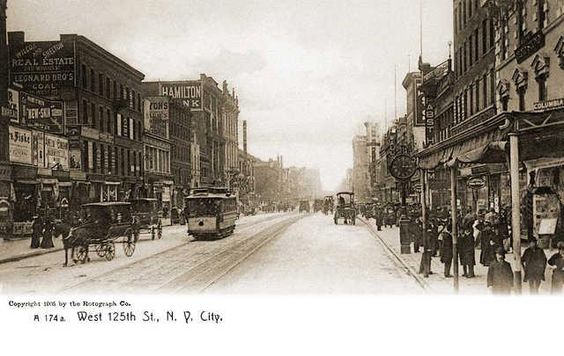

World’s first streetcar began operation in lower Manhattan on November 14, 1832, from 6sqft.com

I view the story Ben is about to tell as epitomizing Dorothy’s pattern of nonchalant neglect. Ben, by contrast, tells it in the same breath as he recounts one of the joys of a New York childhood: his walks to and from his first school, No. 157, “enlivened by the appearance of a St. Nicholas Avenue streetcar drawn by two horses. Our St. Nicholas horsecars were actually the final survivors of that ancient institution.”

Let me set the scene. The year is 1901: Ben is seven, his brother Victor eight, his brother Leon nine. Their father Isaac’s New York branch of the family china shop, Grossbaum & Sons, is thriving. They live in a four-story brownstone in fashionable Harlem. Six days a week, the French governess whom Ben affectionately calls “his Mademoiselle” takes care of the boys. One day a week, their governess takes the day off and the three boys fend for themselves.

“On our mademoiselle’s day off, we three boys were on our own. Once we decided to pay a visit to the little locomotive that pulled the train for kiddies at 65th Street and Fifth Avenue, just inside Central Park. Naturally, we covered the three miles plus on foot. It was a delicious and languid hour or two watching the puffing engine and the little cars make innumerable round-trips. We couldn’t be passengers, of course, since we had no money; but that didn’t seem to make us too unhappy. Then came the long walk home.”

Seven years old is a tender age for a child to spend the day footloose in New York City, in the charge of his scarcely older brothers. I type their address—2019 Fifth Avenue, near 125th Street—into Google Maps, and confirm that it’s a 3.1 mile walk to Central Park at 65th Street. The boys made the 6.2 mile trek and visited the park with no adult, no water (or was there was a drinking fountain?) and no food. Ben Graham’s report makes the adventure sound fun, if you’re a boy Pollyanna. He does admit to feeling tired at journey’s end, but downplays his disappointment at missing out on riding the train. I suspect that at some point, the boys felt hungry and maybe scared.

“It was quite dark when, exhausted, we reached the brownstone house. We paused briefly to decide on strategy, for we suspected that we had committed a major misdemeanor [by coming home after dark] and that severe punishment was in store for us. Leon, as the eldest—all of nine years old—and nominally the responsible head of the undertaking, bravely volunteered to go in first, while Victor and I cowered behind in the protecting shadows. It was indeed a frantic household which greeted its prodigal sons. The police had been notified sometime before, and horrible prospects of kidnappings or accidents were frightening Mother and the help out of their wits.”

My recollection is that Leon and Victor both received sound thrashings, while I—as the youngest and presumably a pliable tool of my brothers—got off virtually scot-free.”

My heart aches for Ben. He explicitly states that this was not an isolated occurrence. Once a week, the three boys were on their own on their governess’ day off. Their father was still alive, earning a good living, but he is either off on one of his business trips, or not mentioned, not even as the giver of thrashings to Ben’s brothers. Vases “of mountainous height,” each worth a thousand dollars, graced their home showroom. Their parents employed three full-time servants. Surely, they could have spared some change to allow the boys to take a toy train ride in Central Park, with enough to cover trolley fare for the return home. Yet neither Dorothy nor “the help” offered or suggested that boys take along some money. No one asked where they were going, nor had any idea where to look for them when they failed to return. I get the impression that the boys often set out on their own on Mademoiselle’s day off, destination unknown. Apparently, they always got home before dark except on this one occasion.

Dorothy Didn’t Go with Them. Why not?

“Limited Express” Railway in Central Park, New York City, 1904, The Library of Congress

Scrutinizing this photo, I notice that women—mothers, governesses—sit with children in the train cars. Well-dressed men, likely fathers, look on. Most children have adults accompanying them. Why not Ben, Victor and Leon? Dorothy’s servants relieved her of most household responsibilities. She sometimes shopped for food, but did not need to cook, wash dishes, launder clothes, or clean the house. If she wished to, she could take her sons on an excursion. You might object, saying she had something pressing to do. Perhaps, but not on every day her children were without a governess and on their own. She never chose to accompany them.

Shopping on 125th Street, New York City

The outings Ben reports taking with his mother entailed shopping on 125th Street, “a fairly fashionable center for upper-class trade,” for shoes, meat, and groceries. For other items, Dorothy shopped at Koch and Co., or on rare occasions, took a trolley to Bloomingdales. On this day, school was closed. If was a Sunday, shops were closed too. Dorothy eschewed recreational jaunts. She only took her boys along—infrequently—when she had errands to run.

Dorothy, who was likely raised by round-the-clock governesses in her well-to-do Warsaw home, may have never experienced the kind of stress-free excitement that an excursion with a parent can engender. Like many parents, she didn’t give her children what her own mother didn’t give her. Ben Graham met his maternal grandmother once, at age seven, on a trip to England. He describes his Grandmother Gesundheit as “a stout, emotional, and domineering lady, just returned from Paris with a glass bottle full of hard candy for us.” Hard candy, but no soft words or hugs.

My tendency to judge others (and myself) rears its disapproving head. A squall of fury swamps me. My great-grandmother Dorothy was in charge that day, and she never bothered to ask where her boys were going. Nor did she weep with relief at her sons’ safe return. If she had, Ben would have said so.

In Her Darkest Hours

Something shifted in me when I found this passage Ben Graham wrote about his mother:

“Money was important to her…as the proof of worldly success. She was ambitious for her sons, and in her darkest hours she was buoyed up by the confidence that in due time we would restore the family fortunes. In fact, she had more confidence in us than we ourselves.”

Ben recalls a time when he was about to graduate high school, and his brothers—both high school graduates—held $10 per week jobs. A newspaper poll suggested that a worker would be happy if he could earn $30 per week for life. Mother asked her sons and they all replied that they would be content with $30 per week. Ben Graham continues: “Mother looked at us with a disdainful smile, and said she would be deeply disappointed if she thought that our ambitions were really as mediocre as all that.”

Dorothy’s Key Motivating Message

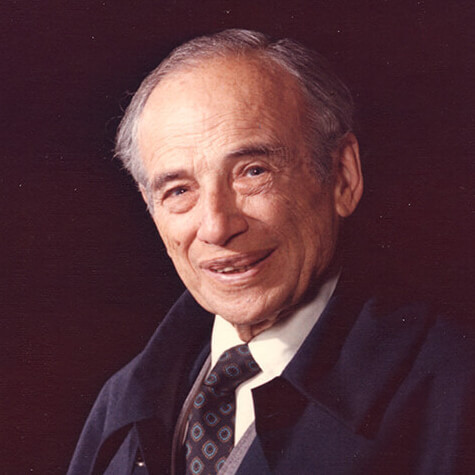

Dorothy’s view of her sons as highly capable brought to mind an article I’d read in which Warren Buffett disclosed that his dad truly believed in him. During my visit, Mr. Buffett reaffirmed that his father, Howard Buffett, was the most influential person in his life. My grandfather was the second most influential.

All at once, I understood. Warren Buffett’s father believed in him! Dorothy withheld comfort and affection from Ben. She told him, when he was young and vulnerable, that she had the impulse to throw his tiny newborn self out the window. She left her little Ben bereft of love.

And she believed in him. She gave him the gift of expecting him to succeed. To reprise Ben’s words: “She had more confidence in us than we ourselves.”

When a Parent Believes in You

Dorothy didn’t communicate and listen with love and respect nor did she encourage her children to ask for help when they needed it. Quite the opposite. She did impart her belief that Ben would succeed. Even a flawed parent can give a child the mettle to push against daunting resistance, to rebound and prevail, as Ben Graham did. To have your parent believe in you is not something to take for granted. I never experienced that. My parents both believed in my father’s superior brilliance, compelling my mother and I to dim our light under a bushel, our Ben Graham DNA notwithstanding. I’m not alone. Millions of wives and daughters in patriarchal families experience diminished expectations, and subtle pressure to shine less than their husbands, fathers, and brothers.

Vitalie Katsenelsen, respected value investor in the Benjamin Graham tradition and author of “The Intellectual Investor” blog, elucidates this issue in his book titled Soul in the Game: The Art of a Meaningful Life. An award-winning writer and CEO of an investment firm, he often prioritizes spending time with his children. Vitalie’s writings offer lovely moments when a parent shows children that their presence brings delight. Dorothy, by contrast, never took delight in Ben. He would have recorded such a marvel in his Memoirs. (I discuss how parents and grandparents can show a child they are valued in this Reflection.) In the chapter “Parents of La Mancha” in Soul in the Game, Vitalie recounts that, as a C student growing up in Russia, his teachers discounted him. “But my parents were like Don Quixote,” he writes. “They always saw a much greater person in me, though I rarely deserved it.” His mother died when he was eleven, but over three decades later, he writes: “I still remember how my mother had this incredible belief in me.” A year after the family emigrated to America, Vitalie’s father told a neighbor within earshot of his teenage son: “VItalie, he’ll achieve anything he puts his mind to.”

Vasilie adds: “Now that I’m the father of three wonderful kids, I try to do the same for them.”

Ben Graham Strove to Prove His Worth

Fortified with his mother’s conviction that he would succeed, Ben Graham graduated college in 1914 and took a $12 per week position at an investment firm. He thirsted to meet—no, to surpass—his mother’s expectations. He put his powerful mind to work on investing in the stock market, and invented security analysis and value investing. He kept on striving—striving to excel at investing, teaching, and writing. Two decades and two years later, he began the legendary run that put him on Forbes’ list of Top Five All-Time Fund Managers—a twenty year period where the fund Ben Graham managed with his partner Jerome Newman earned an estimated return of 21% annually. Ben longed to show his mother that her confidence in him was justified. He longed to prove his worth. And he did.

If you’ve read About Ben Graham on my website, you know that the spectacular success that followed his inventions of security analysis and value investing didn’t make him happy.

Deeming himself worthy of love, healing his wounds, dismantling the “breastwork” around his heart, opening to feelings, opening to love—for that Ben Graham would have to wait until he reached his sixties.

Love was never Dorothy’s strong suit, but I don’t discount the possibility that Dorothy’s belief in him helped make it possible for Ben, late in life, to heal and find enduring love.

My great-grandmother Dorothy Gesundheit Graham was herself a wounded person who had built her own wall around her heart. At last, I feel compassion for her. She was emotionally unavailable, incapable of connecting deeply with her children. She probably grew up not knowing if she was loveable. Ben describes her as “pretty enough to excite admiration everywhere” yet after her husband died, she chose to live alone for the rest of her life. It’s likely that no parent believed in her. Yet she conveyed to her youngest son, Ben Graham, that she believed in him. For that, I love her.