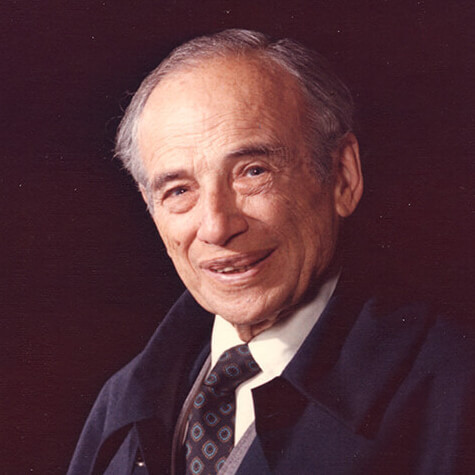

I’m not exaggerating when I tell you that Ben Graham witnessed worldwide panic in his first summer on Wall Street. My twenty-year-old grandfather was no seasoned investor. In July 1914, he must have noted with alarm that Britain was suffering a bank panic due to an excess of customers losing confidence and demanding withdrawals. According to the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA), England was enduring “the most severe systemic financial crisis that London has ever experienced. And not just London. Some fifty countries around the world had financial crises.” What about New York? The Saturday Evening Post asserts that “Wall Street was confronting a massive sell-off of U.S. securities by other countries, potentially leading to a financial disaster.” Why? Because when World War I erupted, foreign investors sold off about $3 billion in U.S. stocks. This sell-off was depleting American gold reserves and threatened to devalue the dollar.

How did Benjamin Graham Fare During This Great Financial Crisis of 1914?

Two months earlier, all Benjamin Graham wanted was to find a good job. He was about to graduate second in his class from Columbia College, a mathematics major with a bent for the humanities, selected for the honor of Phi Beta Kappa. Ben’s father had died fourteen years before, leaving the family penniless. Ben wanted to earn money, enough to support his widowed mother and, he hoped, to marry my grandmother. Yet this brilliant young college man had no idea what kind of job he wanted. He was eager to grab the first prospect that came along.

Missed Opportunity

One day, Dean Keppel—the dean of Columbia who had offered Ben the Alumni Scholarship three years before—told Ben that he had missed a “most interesting opportunity” because the dean had been unable to reach him by telephone the day before. Likely Ben and his brothers were working and Ben’s mother had been out. The dean had recommended Ben to be the assistant to a future Nobel Peace Prize winner, Sir Norman Angell, who had set off for Europe that very day on a mission to spread peace. (World War I would break out two months later.) If Ben had been home to take the dean’s call, he might have found himself in England when war was declared. A British subject who’d been born in London, Benjamin Graham might have been drafted into the British military and shipped off to fight in Flanders Fields.

Benjamin Graham, Mad Man?

In his autobiography, Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street, Ben recounts the next job offer that came his way. A friend named Freddy, who ran a small advertising agency, asked Ben to write some copy for his chief account, Carbona, “the well-known non-flammable cleaning liquid.”

“Since I had some time between the end of classes and Graduation Day, I was happy to take a fling at it. After a few [tries], I produced my masterpiece:

‘There was a young girl from Winona

Who never had heard of Carbona

She started to clean

With a can of benzene

And now her poor parents bemoan her.’”

The president of Freddy’s company “nearly died laughing” over Ben’s limerick. But their client wanted to scare people into buying Carbona—scare them about other products catching fire. Humor “wouldn’t do.” I smile to think what path my grandfather might have followed if that president had invited Ben to join his advertising team.

Academia Beckons

In the interim before his college commencement, a dizzying flurry of offers flew Ben’s way.

“First came an invitation from Professor Woodbridge, Chairman of the Philosophy Department, to lunch with him at the faculty club. He suggested I stay on at Columbia as a member of the Department of Philosophy.”

What an extraordinary job offer. Ben Graham wasn’t a philosophy major. While pursuing his undergraduate studies in mathematics, Ben had taken a course or two in Professor Woodridge’s department. I don’t know how the finest universities in America recruited new faculty members in the 1910s, but I’m certain that department chairs didn’t often take undergraduates to lunch and proceed to offer them teaching posts.

“Soon thereafter came a corresponding offer from Professor Hawkes on behalf of the Mathematics Department. Then, to my surprise, the great Professor Erskine invited me to his office for a chat. He felt that I would make a valuable addition to the Department of English and that I would find a university career most congenial.”

Benjamin Graham, Polymath

Ben might well have found a university career congenial. His professors had noted that the wide-ranging mind of Benjamin Graham shone in these three diverse subjects: Greek and Latin philosophy, English, and mathematics. Like one of the preeminent polymaths in history, Benjamin Franklin, whom Ben admired, my grandfather devoured knowledge on many subjects and used his gifts to solve problems and to innovate.

“True, the starting salary was low and advancement less than rapid.”

Ben “felt both complimented and bewildered by this wealth of offers.” He talked them over with his mentor, Dean Keppel, who advised him to wait.

“[The dean] had a strong predilection for sending bright college graduates into business, instead of shutting them up in the ivory tower of academic life. Perhaps he would be able to steer something interesting my way.”

I put myself in Ben’s shoes and sense how unsettled he must have felt. He had pinned his hopes on Columbia College becoming his stepping stone to a lucrative job. With commencement day fast approaching, Benjamin Graham had no job. He had no idea where he would find employment, much less a niche where his keen intellect and abundant talents could blossom.

A Summons to Dean Keppel’s Office

Right before his graduation, Ben received a summons to see the dean. Mr. Samuel Newburger, a member of the New York Stock Exchange, had visited the dean “about his son’s rather woeful grades.” This visitor then asked the dean to recommend an outstanding student for a starting position in his investment firm.

“Keppel had given this Mr. Newburger my name, with a rousing recommendation. [The dean] was convinced that Wall Street presented fine opportunities for college men and that I ought seriously to consider this career rather than college teaching.”

The next day, my grandfather arrived early for his appointment with Mr. Newburger.

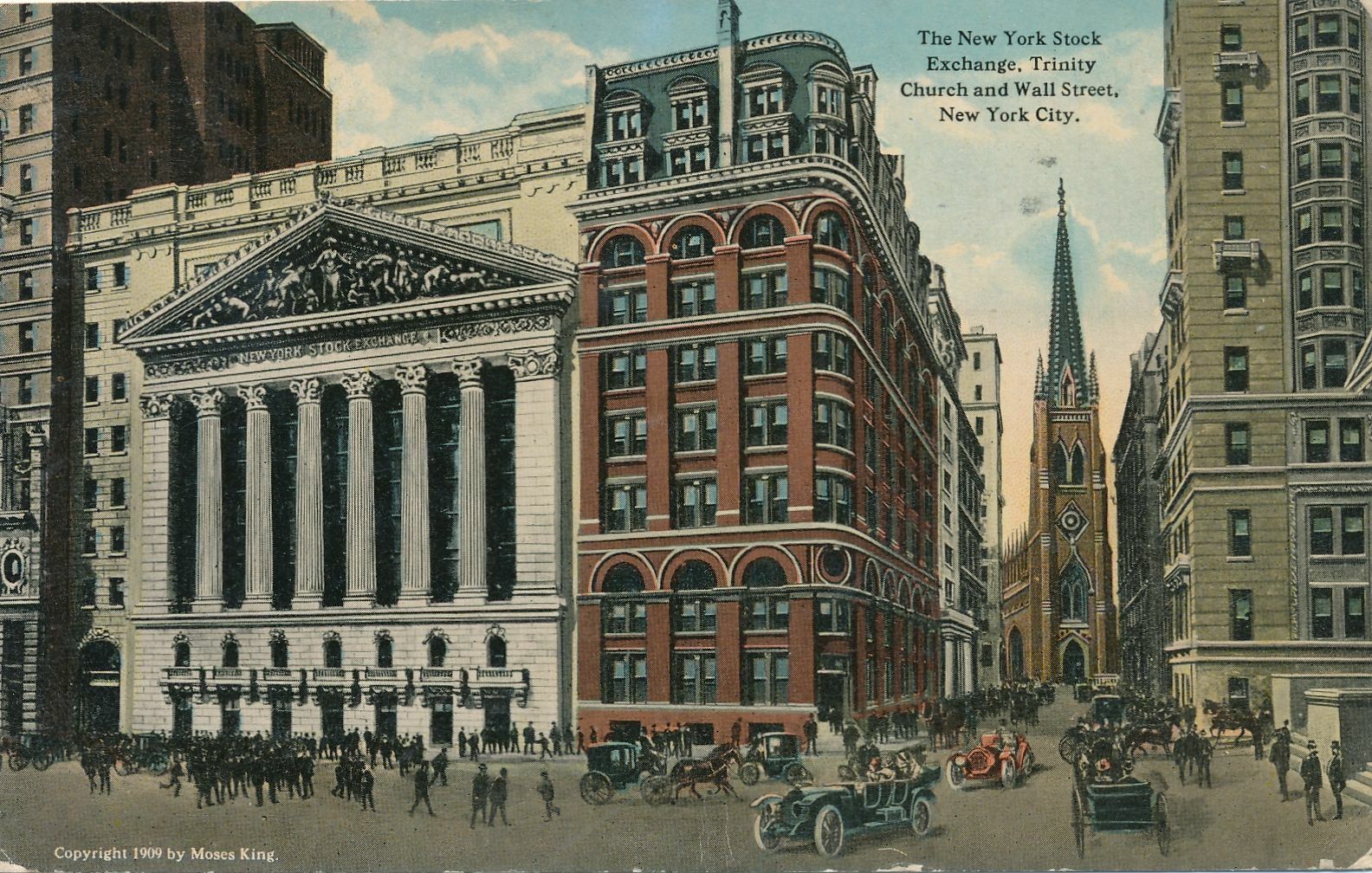

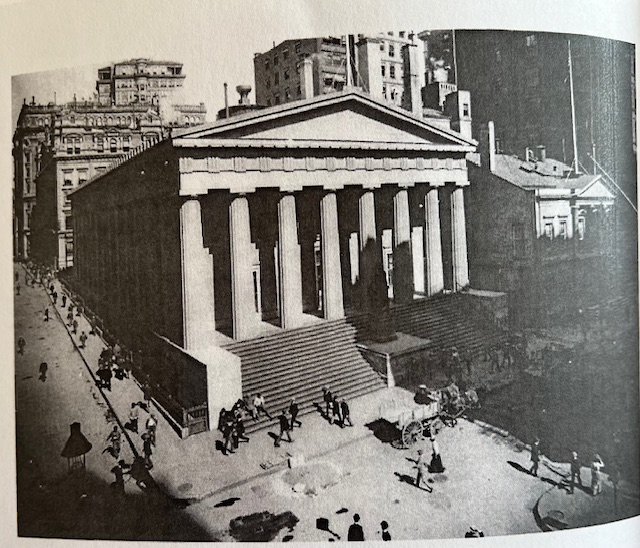

“I well remember…walking up and down in front of Trinity Church clock, waiting for the hands to reach 3:10.”

You can see the location where Ben Graham paced in the postcard featured atop this post. I imagine he felt a frisson of anticipation, sensing his future was at stake. He soon found himself in the office of Mr. Samuel Newburger, who passed him along to his brother Alfred “for my real interview.” Mr. Alfred Newburger turned out to be the “senior member and guiding spirit” of Newburger, Henderson, and Loeb (N.H.&L.), a brokerage firm located at 100 Broadway in New York’s financial district.

Ben Graham Almost Failed His Wall Street Job Interview

“[Mr. Newburger] asked me about my studies in economics, and I had to admit that I had skipped the subject entirely—largely because of my job with U.S. Express. However, I satisfied him that I knew the difference between a stock and a bond. He said that despite my lack of specific training, he would take me on because of Dean Keppel’s sponsorship.”

Dean Keppel had apologized for a clerical error that denied Ben the Pulitzer scholarship in 1910, and he had offered Ben an Alumni Scholarship in 1911. Now the dean had become the benefactor who spoke highly of Ben and opened the door to a Wall Street career. Ben must have felt a mix of relief and elation, now that he had realized his dream of landing a promising job.

Ben proceeded to negotiate a salary of $12 per week, two dollars higher than N.H.&L’s typical starting salary but much less than he’d earned while moonlighting as a college student. Today’s top finance graduates may command substantial salaries in New York but Ben Graham would not be able to make ends meet without tutoring the children of army officers on Governors Island after working his long day on Wall Street.

Drama, Excitement, and a Half-Million-Dollar Check

“[Mr. Newburger] spoke of the great opportunities in Wall Street for the right kind of man. I knew it only by hearsay and in novels as a place of drama and excitement. I felt the urge to participate in its mysterious rites and momentous events. I accepted the terms and agreed to start next week.”

Mr. Newburger closed the interview with these daunting words:

“‘One last warning, young man. If you speculate, you’ll lose your money. Always remember that.’”

By “speculate,” Mr. Newburger meant trading in high risk, volatile stocks and bonds. Benjamin Graham not only heeded his new boss’s warning but also became the father of speculation’s opposite—value investing.

In order to learn the business, Ben started out performing humble duties. He worked as a runner, delivery man, order clerk, and bookkeeping assistant. Right off the bat, he couldn’t believe the laxness he observed. His mother valued every penny and had taught him to take great care with money.

“I was astonished at the financial industry’s easygoing ways of dealing with large sums.”

While working as a runner, Ben would go up to a window, and a check “for maybe half a million dollars would be handed to him with no identification asked.” If Ben was headed to a certain destination, another runner “would thrust a sheaf of stock certificates into my hands and run off.” Ben was amazed that checks and certificates found their way to their rightful owners.

“After about four weeks as a runner, I moved into the bond department, lodged in a single exposed room separated by a narrow corridor from the customers’ room and its quotation board.”

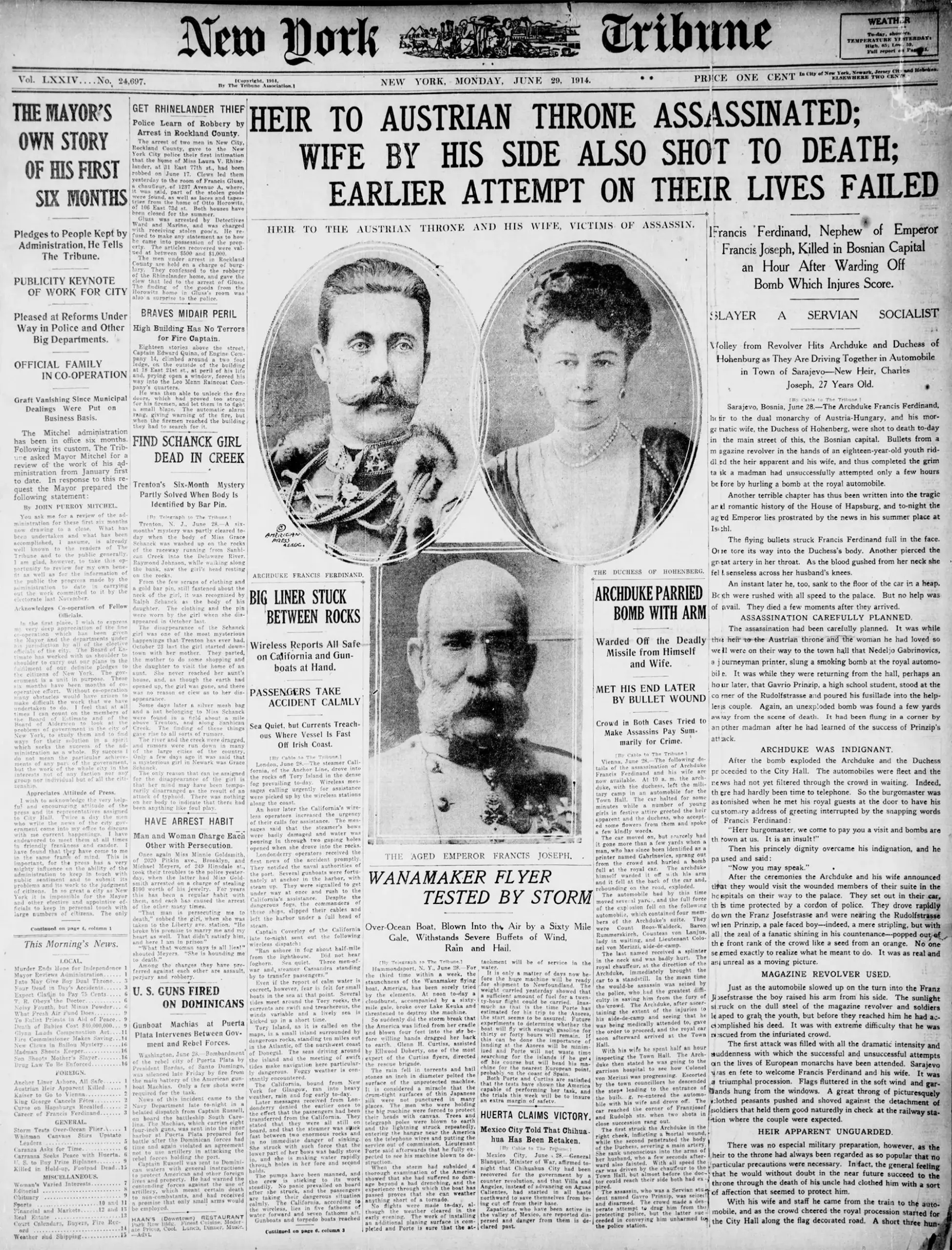

Fatal Shooting Triggers Tension

Then, on June 29, 1914, a calamitous event shook Western Europe.

“The heir-apparent to the throne of Austria was assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia, leading to sharp exchanges between Bosnia and little Serbia. The New York stock exchange paid only slight attention to this European tension; it would probably blow over.”

Ben looks back at the summer of 1914—his first on Wall Street—as “that quiet period, just before the Victorian world was to disappear in flames, and the nineteenth century…was to come to its equally belated close.”

During that calm before the storm, Ben was assigned to write the market letter for the firm’s Philadelphia clients, to give them a daily report of market doings. He called this his “silliest job”—silly in the sense that he considered himself unqualified. I understand his misgivings about writing as “the new expert, who could boast all of six weeks’ acquaintance with finance.”

World War Erupts

Early in August of 1914, World War I broke out.

“Would it lead to the disappearance of Western civilization? …Or was it simply another in the endless series of wars among nations, which ultimately seem to leave no major historical scars but are catastrophic to those who fight them and portentous for those who survive? …I shall write now only from the narrow viewpoint of a young New Yorker who, as the early stages of the drama unfolded, experienced the same bewilderment and excitement as his neighbors.”

My grandfather could not have chosen a more distressing time to launch his finance career. Ben reports that before August 3, the stock market “was showing considerable nervousness but nothing approaching panic.” Then suddenly, foreign investors rushed to liquidate their Wall Street holdings and siphon off American gold to Europe.

Washington Shuts Down Wall Street

“The actual outbreak of hostilities caught the financial community by surprise, both here and in Europe. Our market was swamped by a terrific wave of selling, and very quickly the governors decided to close the New York Stock Exchange.”

To stop the panic selling, Treasury Secretary William McAdoo took the drastic step of closing the stock market on July 31, 1914. The suspension of trading on the New York Stock Exchange lasted until December 12, 1914. According to William Silber, a professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business, shutting down Wall Street for more than four months was just as “unthinkable” in 1914 as it would be today. Yet William McAdoo effectively stopped foreign investors from accessing U.S. gold, enabling America to maintain the gold standard. Silber posits that McAdoo’s skillful handling of the Great Financial Crisis of 1914 empowered America to win out over Britain for financial supremacy.

Monetary triumph never entered Ben’s head. I picture my twenty-year-old grandfather making his start just when Wall Street shuttered its doors. He must have felt like a young player called up to the big leagues, only to see Major League Baseball go on strike.

Insecurity and Instability

“In my mind’s eye, I still see the glaring headlines: Austria declares war on Serbia; Russia declares war on Austria; Germany on Russia; France on Germany; England on Germany. It was all so hard to believe, and yet so dreadfully true.”

War provoked insecurity for many Americans, including Ben. No doubt he hoped that the United States would avoid being drawn into the conflict. If America entered the war, Ben would face the military draft.

“How quickly we all accustomed ourselves to this world catastrophe; how soon we transferred our major interest to its effect on us.”

Ben lived in a small apartment with his mother and two brothers, contributing most of his earnings to his mother’s support. He must have been fearful that World War I, the financial crisis, and suspension of trade on the NYSE would leave him unemployed.

What Happened to Ben?

Relative quiet on Wall Street after the New York Stock Exchange closed its doors, from July 31 to December 12, 1914. Courtesy of the New York Historical Society.

“There was really nothing going on in Wall Street, but all the firms retained their staffs on a reduced-salary basis. I was glad I still had a job.”

Ben’s bosses lowered his salary from $12 to $10 per week. His pay seemed awfully low to begin with, and I’m sure the $2 per week reduction created a hardship. Thankfully, N.H.&L. kept him on the payroll.

Gloom to Boom

“Before long, war orders started coming in from the French and British, and the economic picture changed quickly from gloom to boom.”

When the Stock Exchange reopened, the subsequent war boom gave Ben Graham a shot at trying out different roles.

“We were caught rather shorthanded by this sudden reversal, since a number of our employees had drifted away. As a result, I was called into service on many fronts.”

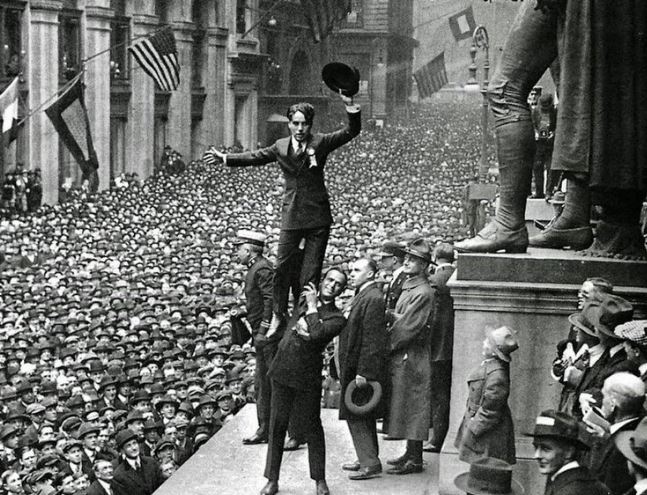

Benjamin Graham wore a “heavy leather belt” that held “fractions from 1/8 to 7/8” on the days he worked as a board boy, putting up stock quotations in the customer room. He operated the telephone switchboard or hustled to deliver securities. He put in time in the bond department, where he called upon businessmen and attempted to sell them bonds. He tells us that their “‘No’ was invariably polite.” Ben makes it sound as if he never sold a single bond. Were he to try to sell bonds on Wall Street today, Benjamin Graham might attract a crowd. In the photo below, Charlie Chaplin shows us how it was done, albeit in 1918, when the government enlisted celebrities to urge Americans to help finance the war effort by purchasing Liberty Bonds.

Silent movie star Charlie Chaplin drew a crowd of twenty thousand people on Wall Street, who heard his voice for the first time. In 1918, he aimed to sell Liberty Bonds to help America win World War I.

Failed Bond Salesman, Born “Statistician”

Ben’s assignment to the bond department gave him the leeway to pursue avenues of inquiry that interested him. He “diligently read…the standard textbook on the subject,” The Principles of Bond Investment by Lawrence Chamberlain. As a sideline, he studied railroad reports.

“On the basis of these studies, I conceived the idea of writing an analysis of the Missouri Pacific Railroad. Its report for the year ending June 1914 had convinced me that it was in poor physical and financially dangerous condition and that its bonds should not be held by investors.”

Ben showed his Missouri Pacific Railroad report to a friend, who passed it along to a partner at J.S. Bache and Company. Bache’s top brass were so impressed, they offered Ben a job as a “statistician” at a salary of $18 per week. Ben Graham realized that his razor-sharp analytical brain was uniquely suited to this kind of work. The rookie who struck out at bond sales hit his first bond analysis out of the park.

“This was all very wonderful!”

“Wonderful!” That’s how my grandfather expresses his exhilaration when, in his Memoirs, he leaps back fifty years to this pivotal moment. Benjamin Graham not only survived world panic, but also thrived in its aftermath. Ben’s first effort as a “statistician” would spark a pyrotechnic display of innovation, including the invention of security analysis. Stay tuned for the story of how Benjamin Graham effected his first arbitrage operation—and married my grandmother.