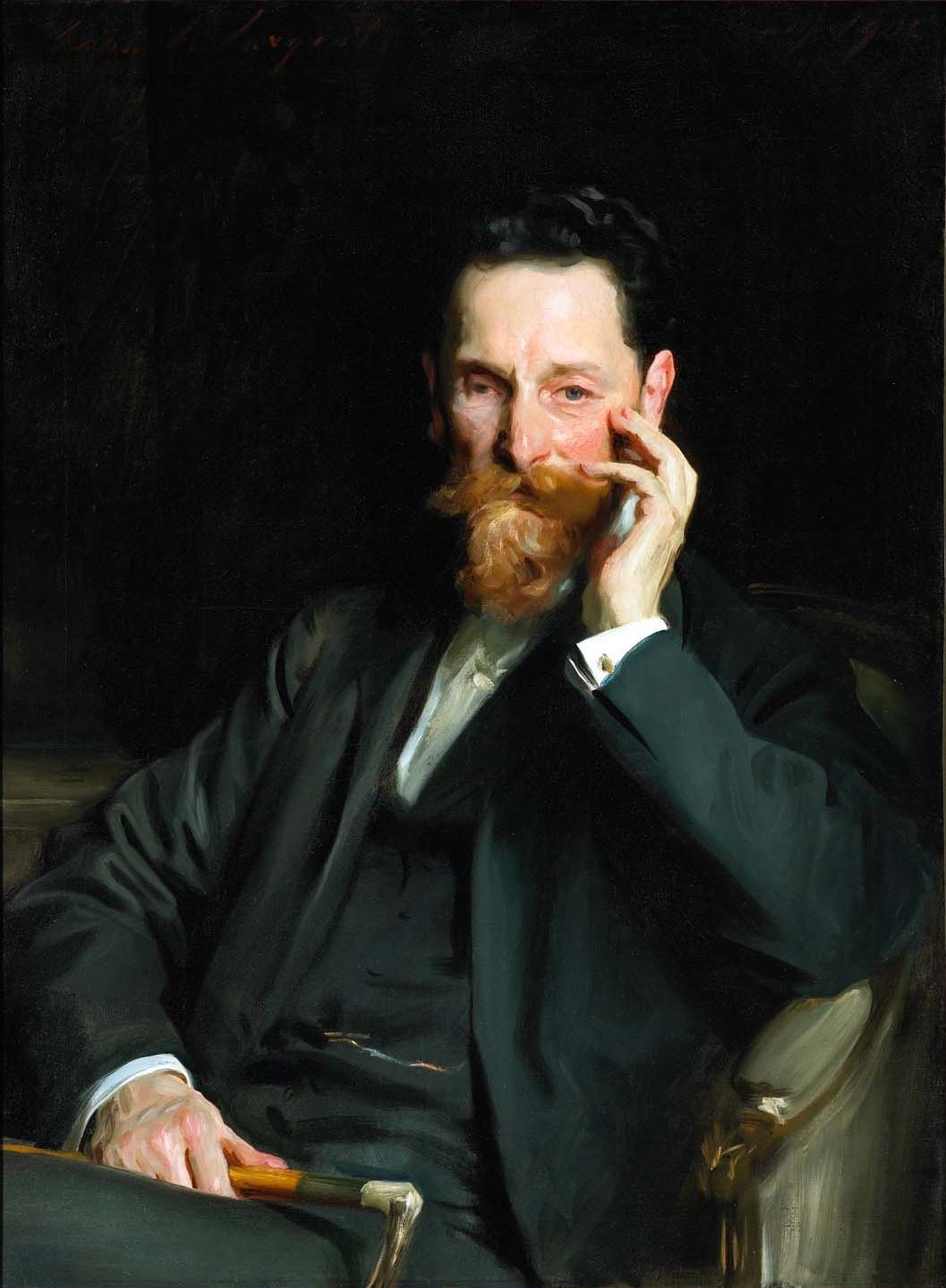

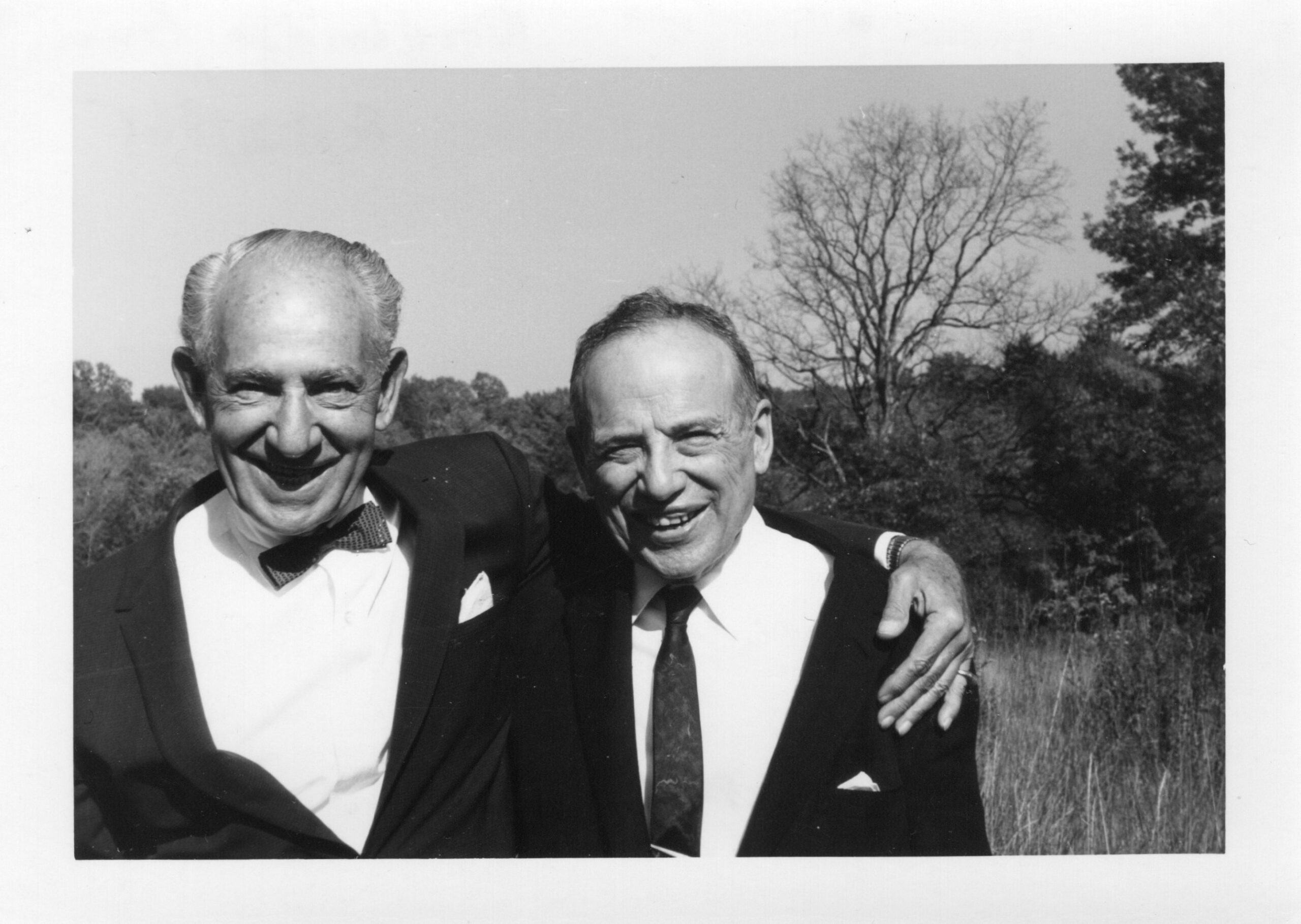

I didn’t understand Ben Graham when I was a little girl and he was my “Grandpa Ben.” He was rich, so I thought his life was perfect. At age sixteen, I didn’t understand him when he took me on a cruise to the Black Sea; nor did I see him clearly the summer he welcomed me to his Aix-en-Provence cottage when I was twenty-one. I still didn’t fathom him in my forties when, two decades after his death, I began to pore over his book, Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street. Reading his account of his boyhood felt like playing hide-and-seek. I sought, he hid; he revealed, he concealed; until at book’s end, he divulged his secrets—partially but significantly.

After my second reading—or was it my third?—I thought I’d gleaned what happened to Grandpa when he was a boy. I knew about some of the hard experiences that shaped him. I knew him to be my grandfather, related to me not only by blood but also by a shared thirst for inner truths that empower a person to heal and grow.

My breakthrough came when, nearing the end of the Memoirs, I read the chapter titled “Epilogue: Benjamin Graham’s Self-Portrait at Sixty-Three, May 1957.” Here, Grandpa Ben hides a newfound understanding of his early emotional trauma in plain sight. Because he does not spell out the nature of this trauma, I combed the early chapters of the Memoirs for what I call his “worst memories.” These memories detail the cutting words and actions that were directed at Ben, the boy.

Studying the “Epilogue,” one might easily miss his insights among the plentiful comments about his own character, some of them unflattering. His two most crucial insights may not immediately strike you as important. You might find them unsettling. I invite you to give them a chance to grow in meaning for you, as they did for me.

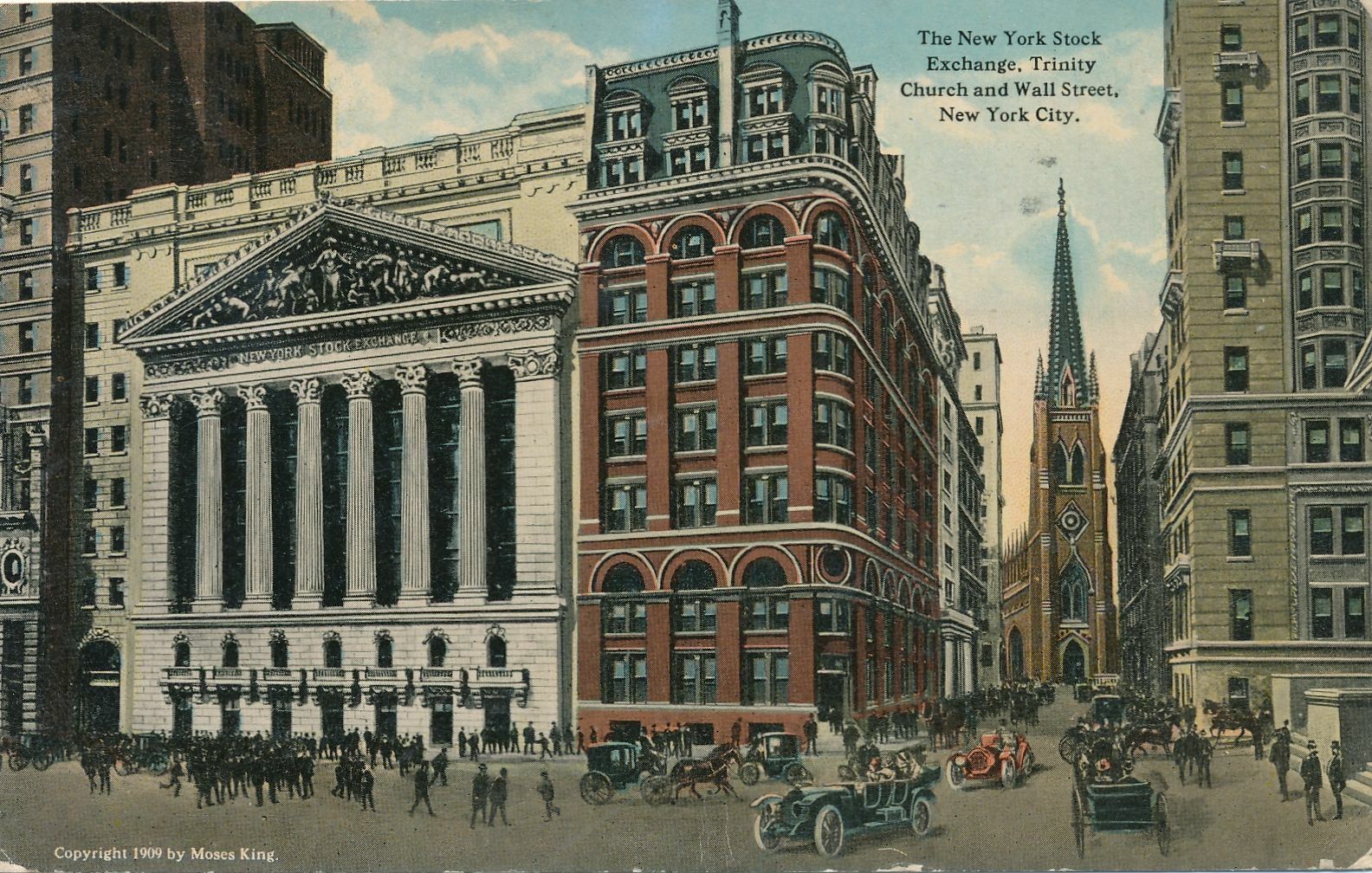

Benjamin Graham wrote his “Self-Portrait” a year after he made a decision that stunned everyone who knew him. At the peak of his success, he closed the Wall Street office where he managed the Graham-Newman mutual fund, retired from the investment business, and moved to Beverly Hills. A year after his relocation, he began to write autobiographical vignettes.

At first, I found it hard to get accustomed to his use of the third person in the “Self-Portrait”: “As a boy, he was bright, winsome, awkward, impractical, and morbidly sensitive.” Perhaps the only way Ben Graham could give himself compassionate understanding was by referring to himself as “he.” If he saw himself as a character in his own life story—just as Odysseus is a character in the Odyssey—then that might also incline him to refer to himself in the third person. (The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines “winsome” as “winning or innocently appealing in appearance, character or manners.” The studio photograph of Ben at age two, posing with his two older brothers, certainly displays Ben’s endearing innocence and charm.)

Ben Graham’s first key insight:

“As a boy… he was careful never to wound anyone, and he could not understand how others, including those who loved him dearly, would so often wound him, with nonchalance or even with malice.”

Ben’s statement strikes me as rich with meaning and mystery. I wonder why he didn’t reverse its logic, and say that his experience of being wounded caused him to take care not to hurt other people’s feelings. Another conumdrum: who are the people who wounded him? Those who loved him dearly. He’s not talking about mean kids at school, or the anti-Semitic bullies who taunted him in the street, though he experienced that, too. Those who loved him dearly can only mean the people closest to him: his father, his mother, and his brothers Leon and Victor. There was no one else who loved him when he was a boy. I add his first wife Hazel, my maternal grandmother, to this list because Ben was young and vulnerable—eighteen when they met, twenty-three when they married—when she entered his life.

So who “would so often wound him, with nonchalance or even with malice?” His five closest family members.

Bear in mind that when writing his “Self-Portrait” in 1957, Grandpa Ben neither named who wounded him nor disclosed the nature of the wounds they inflicted. It wasn’t until he sat down to write “Things I Remember,” five or ten years later, that he recounted those “worst memories” I previously mentioned. These telling memories—buried in the Memoirs among plucky anecdotes about his youth—offer clues and sometimes explicit evidence of painful interactions with his close family members. Taken in their totality, they show me that he suffered cumulative emotional trauma as a result of repeated incidents where one of his parents or older brothers said or did something hurtful, or withheld essential caring, at a time when he depended on them.

The hurts he experienced included verbal cruelty; witnessing frightening threats; neglect; failure to give comfort and protection; lack of sympathy for his injuries; leaving him to fend for himself at an early age; and probably beatings and/or humiliation at the hands of his older brothers. I imagine my Grandpa Ben would throw up his hands in protest, if he heard me sum up his experiences this way. Nevertheless, he’s the one who wrote them down. I will discuss the evidence he provided in subsequent blog posts that explore his relationships with each of his family members.

Given the troubling nature of this material, it’s not surprising that he struggled with inner conflict while writing “Things I Remember.” The sense of hide-and-seek I detected when reading the Memoirs may have stemmed from Ben Graham’s dueling desires: to express his woe at the painful experiences he endured as a boy and young man, and at the same time to avoid admitting that the people he relied upon hurt him deeply. Grandpa Ben tended to regard his family members through an uncriticial lens. He may have felt shame for whatever he thought he’d done to deserve unkind treatment. Judging himself as not good enough may have allowed him to see his family members as trustworthy and devoted. He believed they “loved him dearly” despite their (at times) unloving actions and words.

The episode described in Blog Post #2 reveals this inner conflict. In Chapter One of the Memoirs, he relates how his mother told him—when he was a little boy—that she had wanted a daughter and that, when he was born, “her first impulse was to ‘throw [him] out of the window.’” He simply recounts this emotionally charged story without commenting on it. He neither considers how her wounding statements affected him, nor examines how they might have challenged his view of his mother as a “lily” (as he declares her to be in Chapter Two). He excuses her verbal blow by saying “to spare my feelings, she always added that she was happy she hadn’t” (thrown him out the window.) Without pausing for introspection, he launches into a digression about his namesake in the Bible. His waxing on about how the Old Testament Benjamin produced more children than any of his brothers strikes me as an avoidance strategy, to gain him emotional distance from a painful memory.

Let’s circle back to the first phrase of Ben’s insight: “He was careful never to wound anyone.” In the “Self-Portrait,” he also deems his boyhood self “morbidly sensitive.” So he was sensitive both to injury and to other people’s feelings. Did he also have an innate capacity for empathy? That’s harder to discern. I think it likely that his boyhood modus operandi–taking after-school jobs and bringing home his earnings to his mother—arose out of sympathy, not empathy, for his mother. While sympathy isn’t indentical to empathy—one who sympathesizes doesn’t vicariously experience the thoughts and feelings of another—it is a form of caring. I appreciate this quality in him, because no parent or sibling acted as a role model of caring behavior for Ben. After his father died when Ben was eight, his mother struggled to feed, clothe, and house him and his two brothers. He did everything he could to relieve her distress.

Ben’s second key insight explains how his sensitivity and sympathetic impulses became blunted. In my discussion of his first key insight, I have focused on one example—“throw (him) out the window”—but I plan to demonstrate in successive blog posts how all his close family members, including his first wife, wounded him with words and deeds.

Ben Graham’s second key insight:

“Very early in life, he set to work like a beaver, to build a breastwork around his heart.”

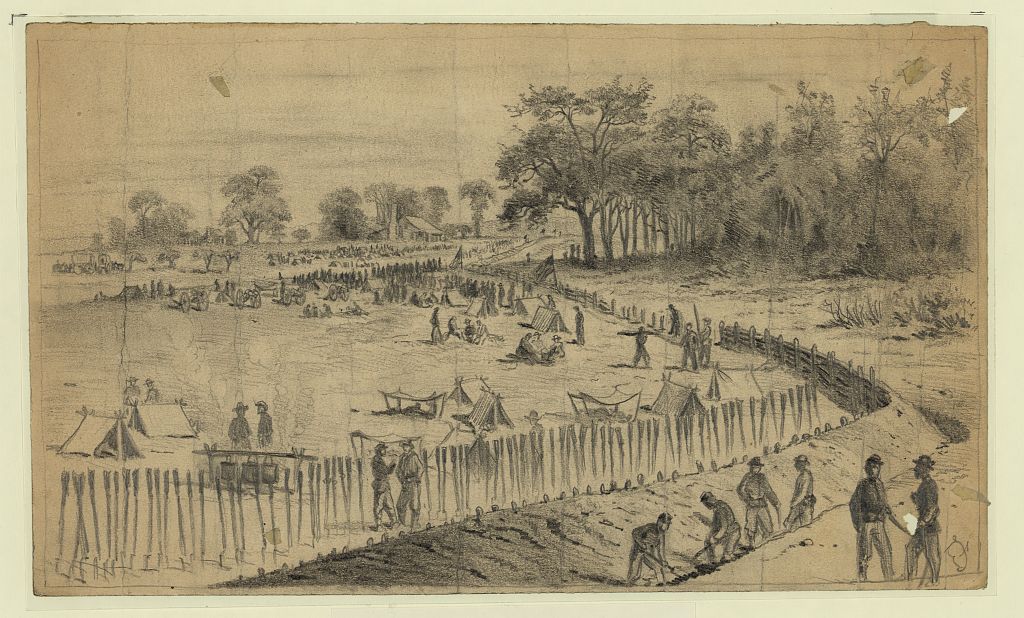

An archaic word, “breastwork” means a defensive wall that soldiers build when under attack.

Battle of Cold Harbor, Virginia, 1864: throwing up breastwork

The word “breastwork” was not in common usage in 1957 when he wrote his “Self-Portrait.” “Breastwork” does, however, appear in Homer’s Illiad as well as Virgil’s Aeneid, Greek and Latin classics admired and oft-read by Ben from his boyhood on. Here’s one example, from Theodore C. Williams’s 1910 translation of the Aeneid:

While on this errand their swift steps are sped

Aeneas, by a shallow moat and small,

his future city shows, breaks ground, and girds

with mound and breastwork like a camp of war

the Trojans’ first abode.

I picture the hero Aeneas wielding a pick to break ground. He forms a dirt mound that he proceeds to fortify into a chest-high breastwork to protect his men, using materials at hand—logs, stones—until the Trojans’ abode has been transformed into a “camp of war.”

Ben labored to build a breastwork inside himself. Like a beaver, he constantly shored up this protective barrier. He needed an inner wall to fortify his heart against the wounding he suffered at the hands of “those who loved him dearly.” How fascinating that he saw his emotional life in both literary and military terms.

The price? His defensive wall blocked him from feeling a deep connection to other human beings. This “breastwork” sheds light on why Ben—an amiable man with an affable smile—had many friends but no close friends or “chums.” The wall around his heart also helps to explain Ben Graham’s three failed marriages. It may explain why he wrote “those who loved him dearly” and not “those whom he loved dearly.” Until he underwent his transformation, he had difficulty sustaining feelings of love, especially toward those whose actions he found hurtful. His inner wall not only shielded him from heartache but also closed him to affection, love, and friendship

Broadcast journalist Anderson Cooper, in his podcast “All There Is with Anderson Cooper: Episode 1, Facing What’s Left Behind,” describes a similar phenonmenon in himself:

“I see now how much of a wall I created around myself after my dad died and after my brother, a wall so that I wouldn’t feel hurt again. And that works but it also means you don’t really feel anything else again either, ever.”

It doesn’t surprise me that jourmalist Anderson Cooper acknowledged his own protective wall in 2022. That Benjamin Graham discerned the wall around his heart—a wall that required constant effort to fortify it—in 1957 astonishes me. Here was this aloof and cerebral Wall Street financier who—after devoting his life to rational investment at the cost of emotional connection—took an unprecedented leap toward understanding his own psyche. He did so, at age sixty-three, without the benefit of psychotherapy.

Aeneas and his family fleeing Troy, by Agostino Carracci, 1595

However, he did have the help of classical literature. The Odyssey and the Aeneid familiarized Ben with the hero’s journey, as described by Joseph Campbell, in which the hero overcomes obstacles and gains knowledge that empowers him to return, transformed, to a safe haven. Even so, unlike those of us alive today, he lacked the cultural familiarity with inner growth that we may gain from partaking of the life lessons of Oprah, Brené Brown or Cheryl Strayed; watching Tony Soprano discuss his mother with his psychiatrist or Ted Lasso admit his darkest secret to the team therapist; or reading the work of childhood trauma pioneers such as John Bowlby, Bessel van der Kolk, and Richard Schwartz.

At sixty-three, Ben Graham understood what had happened to him as a boy. He realized that his close family members had hurt him. He saw that he was wounded. He no longer blamed himself for being “remote and inaccessible to others.” He saw that he had needed to close himself off to feelings, in order to survive. What evidence do I have that his two key insights enabled him to surmount those obstacles and open his heart to love? I have my own observations, from the time he and I spent together in his last decade of life. The man described by his third wife Estelle as “humane, but not human,” who a mentee characterized as a man who “always had a shell around him,” and who portayed himself as “wrapped in the insulation of confident superiority” became my welcoming Grandpa Ben.

I was a young child when Ben Graham began a new life with the woman he called his “priceless Malou.” My mother, Ben’s eldest daughter, never told me how they met, nor of the sadness caused by his marital breakup. Her keeping me in the dark freed me—as a teenager and young adult—to see them as that rarity in our family: a happy couple. Ben and Malou lit up in each other’s presence. Their gratitude at having found one another was palpable. Bruised by my own struggles, I took solace from their affectionate glow and their acceptance of me. My grandfather gave me hope that someday I might find a safe and loving relationship of my own. Now that I know how wounded he was, I find it extraordinary that my grandfather healed himself sufficiently to forge a tender and enduring relationship late in life.

By recognizing his own traumatic wounding, Ben Graham gained the strength and insight he needed to find ultimate fulfillment. In subsequent blog posts, I explore Benjamin Graham’s most difficult boyhood experiences in order to deepen our understanding of how he became an inspirational figure.

Next: Love Hurts: Ben Graham’s (Not So) “Marvelous” Father