Shortly after my husband and I settled ourselves in the conference room at Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett ambled through the door, dressed in a white mock turtleneck under a cornflower blue V-neck sweater. Belying the whiteness of his tousled hair, Mr. Buffett’s pale blue eyes shone with youthful eagerness as he remembered how my grandfather, Ben Graham, offered him a job in 1954. He and his wife Susie had recently had a baby, and were expecting their second, but that didn’t stop them from leaving Omaha for New York so that Mr. Buffett could fulfill his dream of working with his mentor from Columbia Business School. When their son Howard was born, Ben gave Mr. Buffett a movie camera as a gift, encouraging him to take film clips of his growing family. Warren Buffett told me he was struck, time and again, by Ben’s thoughtfulness and generosity, “never expecting anything in return.”

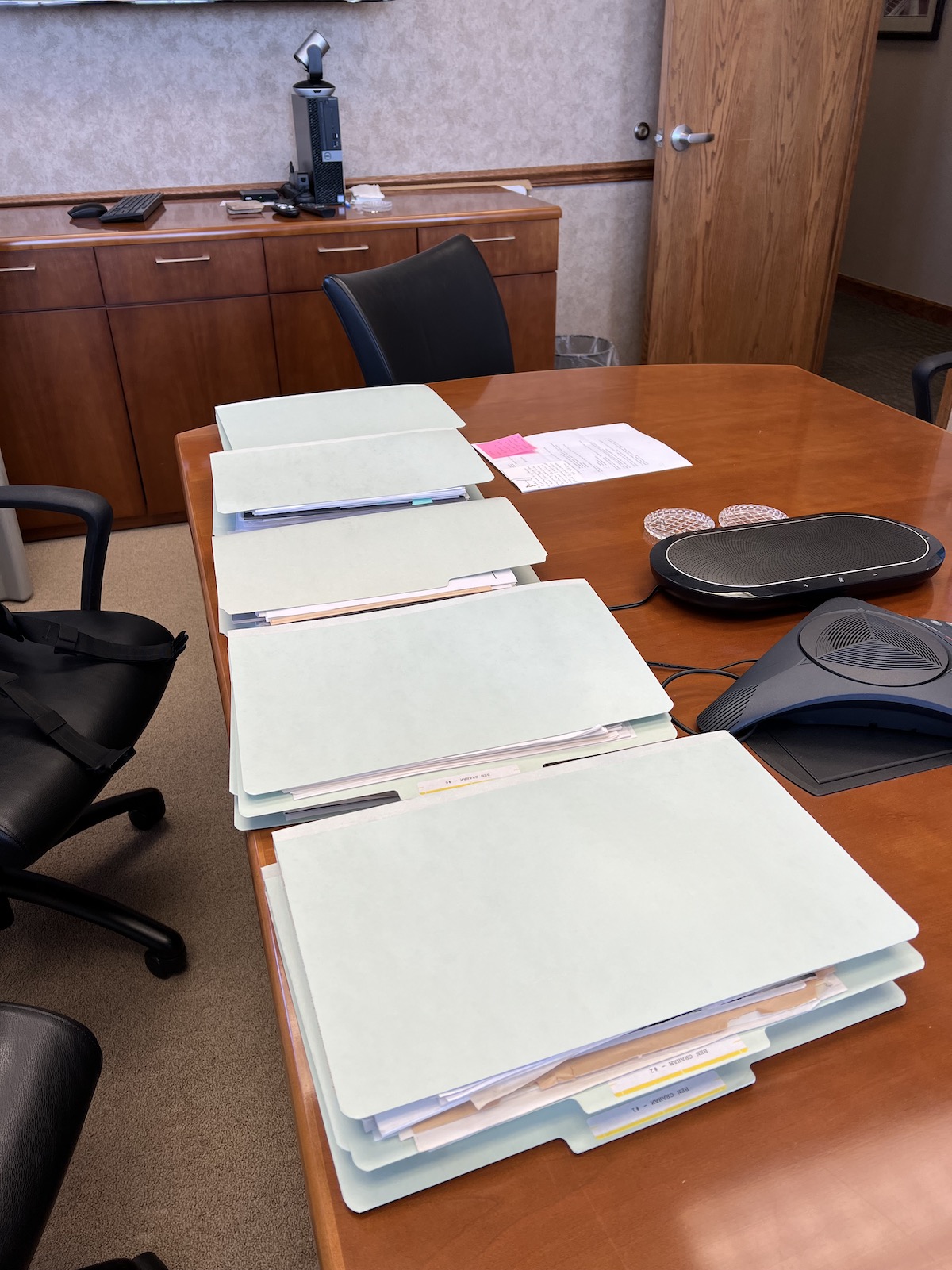

I’d flown to Omaha with my husband, at Mr. Buffett’s invitation, to go through six decades’ worth of Mr. Buffett’s personal papers and select documents for the Benjamin Graham Archive to be housed at Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. We’d just opened the first folder on a spacious wood table when Mr. Buffett, age ninety-two, entered to welcome us.

I wanted to be fully present for our conversations with him, and to remember every word Mr. Buffett spoke about the man I knew as “Grandpa Ben.” My pen flew across the page of my lined tablet while I made eye contact with him, registering the warm tone of his folksy voice and the smile that played poignantly on his lips as he recalled my grandfather:

“Ben did so much for me. I never saw him do an unkind thing.”

“When I worked with him,” Mr. Buffett continued, “Ben told me: ‘Don’t worry too much about making money. It will change how your wife lives but not how you live.’” Mr. Buffett laughed gleefully. With a jovial smile, he remembered Grandpa Ben’s advice to him: “‘You and I will still wear the same clothes and eat at the same cafeteria, so relax.‘”

In that same vein, he told us: “Money didn’t mean that much to Ben.” He continued, “Ben was never that interested in investing. He did it to make a living.” This comment reminded me of how much Ben wanted to ensure that his mother would never again be poor. He applied his powerful brain to the task of making a living—and ended up inventing security analysis and value investing.

“Ben made a huge difference in my life,” Warren recounted. His being on a first-name basis with my grandfather, coupled with his relaxed manner, had transformed him from “Mr. Buffett” to “Warren” for me.

I told him that my grandfather made a huge difference in my life, too. That was the reason I’d come to Omaha. “I want to preserve my grandfather’s legacy,” I proclaimed.

“Ben Graham will be long remembered,” he assured me. “You don’t need to worry about that.”

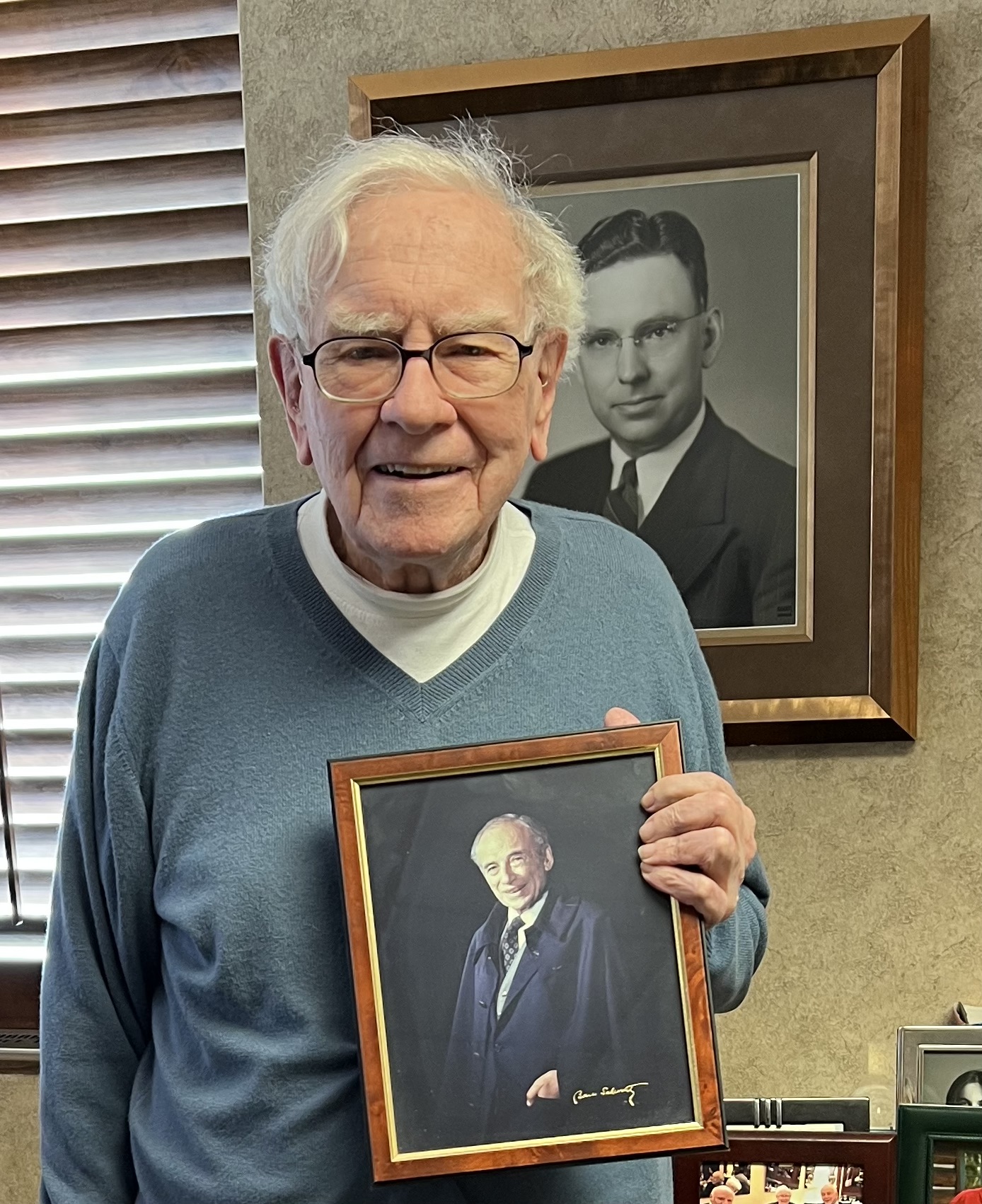

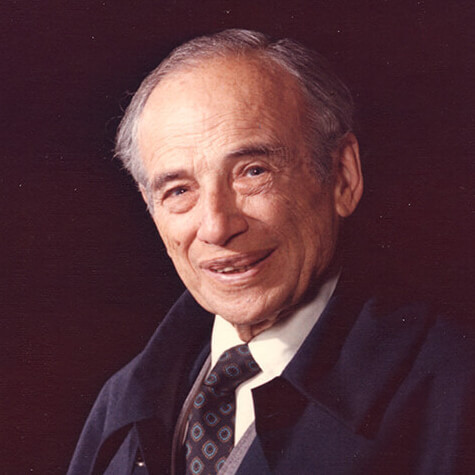

Upon entering Warren’s office, my eyes swept over his desk, with its hodgepodge of papers that had escaped the confines of their in-box and spread willy-nilly across its surface, sharing prime real estate with a rolled-up towel, a TV remote control, a pen, and a pair of rumpled surgical masks— the desk of a man who gives free reign to his wide-ranging mind’s creative impulses. A computer was conspicuously absent. Armchairs and a coffee table lent spaciousness to the room, and a dozen framed photographs graced a wooden credenza. A large, gold-framed portrait of Warren’s father, Howard Buffett, presided over the room from its commanding spot on the wall. Directly below this portrait, on the credenza, sat a smaller framed portrait of my grandfather in his eighties.

“Ben and my father were the major contributors to any success I may have achieved.”

Warren Buffett, in a letter to my mother dated March 22, 1982

Warren wanted me to know that he displayed not one but two photos of my grandfather. He pointed out a photograph, circa 1950, of a younger Ben with David Dodd, Ben’s co-teacher and co-author of Security Analysis. Then Mr. Buffett picked up the first portrait of Ben, and holding it to his heart, posed for a photo:

Warren Buffett stands in front of his father Howard Buffet’s portrait, holding a portrait of Benjamin Graham.

The following day, I showed Warren the photos I’d brought, including one of a vigorous swimsuit-clad Ben holding me (age three) on his shoulder, and one of Ben’s third wife Estelle (“Estey”) with me (age five) dressed in our finery at the wedding of Ben’s daughter Winnie.

“I admired Estey enormously,” he enthused. I told him I had often stayed with her in Beverly Hills, including after Ben and Estey split up. I knew her as my “Grandma Estey.”

“My wife Susie and Estey were fast friends,” he replied.

I handed him a snapshot from 1972 of Ben (age seventy-eight) with the soulmate of his later years, Malou, and me (age twenty-one), sitting on a stone wall overlooking Picasso’s Castle in Provence. Warren’s eyes crinkled with fondness. Unmistakably, this reserved man, considered to be the most successful investor of all time, felt affection for my grandfather.

I suspect that ours was an unusual encounter for Warren, with no talk of investments, stocks, earnings, companies, banks, and the economy. Instead, I asked him, “How did Ben treat you, when you went to work for him at Graham-Newman?” In 1954, Warren had been twenty-four years old.

“Kindly. Ben treated me kindly. Same as he treated everyone else in the office,” Warren asserted.

I pictured my grandfather, his ready smile, his benevolent presence, the way he had welcomed me to his Aix-en-Provence cottage when I arrived for an unannounced visit, scruffy from weeks of camping, my long hair in dire need of a wash, at the age of twenty-one.

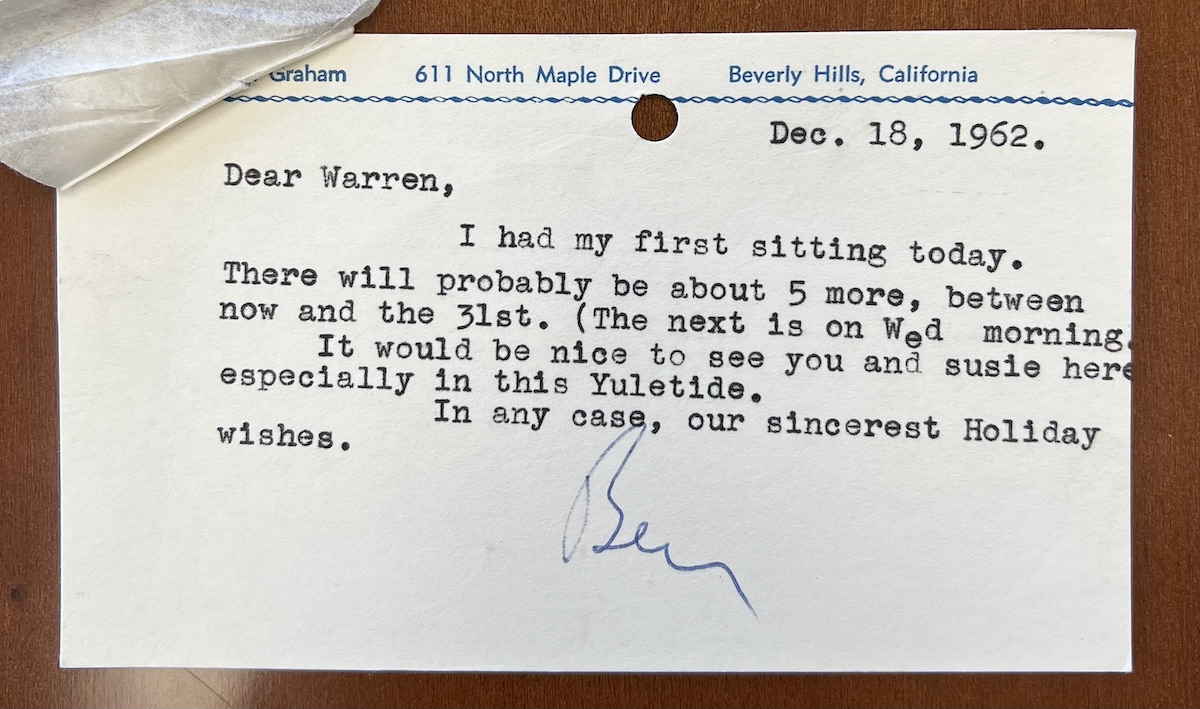

On our second visit with Warren, I asked him: “Would you say that you and Ben became friends?” When he didn’t answer right away, I continued: “In some of Ben’s letters and postcards in your files, he expressed a wish for you and Susie to visit him in California. That sounds like friendship to me.”

“Well, I think I wanted the friendship more than he did.” Warren paused, and when he spoke again, his voice cracked. “Ben was my hero and my friend.” His light blue eyes widened and his face took on a youthful, eager, and fierce expression. “It helps to have heroes who are better than you.”

I felt honored to be in the room. A deep, essential part of me perceived, from the tenor of Warren’s voice, his fervent gaze, that Warren loves my grandfather. Not just back in the ’50s when he venerated Ben as his most admired Columbia Business School professor and his dream boss. Not just in the late ’50s when he and his wife Susie stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel and joined Ben and Estey for dinner, or in 1968 when Warren organized a tribute to his mentor by convening a “select” group of twelve of mostly Ben’s former Columbia students (including himself, Walter Schloss and William Ruane; Charlie Munger was invited as an honorary mentee) on Coronado Island in San Diego to listen to Graham. Warren wrote them:”….[He (Ben) is the bee and we are the flowers!” Ben died in 1976, and Warren still finds meaning in his relationship with Ben. We humans have the capacity to feel love for a person who has passed—love that nourishes the soul and informs how we live. Warren’s heartfelt connection with Ben continues to sustain him.

Moments later, my own heart caught and turned over. I still love my grandfather! I feel his loss. Grandpa Ben is my hero, too. Here I was, learning how to access my feelings from the Oracle of Omaha who is known for being plain spoken about money, not love. Why is Ben my hero? He endured so many blows that could have broken him, rendering him selfish, mean-spirited, greed-addled, lonely, and unreachable. Sure, Ben made mistakes and some hurtful choices; yet to this day, he exemplifies kindness and generosity in the mind of his most prominent protégé.

The enduring bond between these two brilliant investors, Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett, turns out to be less about money and investment strategies and more about character, generosity, and magnanimity—qualities the world sorely needs to counter greed and strife and overconsumption—than I ever expected.

Ben Graham is one of Warren’s heroes. Who were Ben’s heroes? Grandpa Ben told those of us present for his 80th birthday speech (published in the Memoirs) that Benjamin Franklin was “the character after whom I have consciously modeled my life.” Ben Graham aspired to Ben Franklin’s “high intelligence, application, inventiveness, kindness, and tolerance of others’ faults.” Ben also paid homage to his literary idol, Ulysses, writing in the Memoirs that “the wiliness and the courage, the suffering and the triumphs…carried an appeal for me which I never could quite understand.” Unlike Warren, Ben never developed a deep personal attachment to a flesh and blood hero like the bond with my grandfather that Warren disclosed to us.

It would be fascinating to trace how Warren distilled elements of the heroes Benjamin Franklin, Ulysses, Benjamin Graham and his father Howard Buffett, who had “unlimited confidence in me, even when I screwed up” into Warren Buffett’s strong character and masterful leadership style. Warren, in turn, has become a hero to millions.

How was Ben “a hero who was better than him?” Here’s how Warren assessed Ben Graham in The Financial Analysts Journal in 1976:

“Certainly I have never met anyone with a mind of similar scope. Virtually total recall, unending fascination with new knowledge and an ability to recast it in a form applicable to seemingly unrelated problems made exposure to his thinking in any field a delight.

But his third imperative–generosity–was where he succeeded beyond all others. I knew Ben as my teacher, my employer and my friend. In each relationship–just as with all his students, employees and friends–there was an absolutely open-ended, no-scores-kept generosity of ideas, time and spirit.”

In his gracious treatment of me and my husband, Warren embodied the kindness and generosity he saw in Ben Graham. He treats the twenty-four staffers who work with him at the Omaha office considerately too. Investment manager Ted Weschler appeared relaxed and glad to be there. Each person we chatted with in the lunch room seemed at ease and content, in marked contrast to the stressed employees I have encountered in Bay Area tech firms.

Warren Buffett follows in Ben Graham’s footsteps by manifesting kindness in his treatment of shareholders, and compassion in his way of conducting business. For example, back in the ’70s, Warren Buffett stood up for Berkshire Hathaway textile workers the way Ben Graham advocated for ordinary investors when Ben compelled Standard Oil to distribute surplus cash to shareholders in the 1928 Northern Pipeline contest. From a business standpoint, Buffett knew he should close the failing Berkshire Hathaway textile mill and invest its assets in a profitable enterprise, but he chose to keep it open in order to give the workers a livelihood.

Inspired by his hero Ben Graham’s generosity, Warren Buffett has far surpassed Ben in giving to charity. In 2022, according to Forbes, Warren’s 17th annual summer gift brought his total lifetime giving to charitable foundations to a record $48 billion, “[solidifying] his place as the likely biggest philanthropist of all time.”

Warren evinced my grandfather’s “open-ended generosity of spirit” on the morning he strode into the conference room and sang the praises of the gift I’d brought for him and his wife, lauding its “style, workmanship, and care for detail” and proclaiming with persuasive vehemence that “we both very much appreciate it.” I felt he was the one giving me a gift—of his time, attention, and munificence. He reminded me of how my Grandpa Ben praised and appreciated everyone except himself. For instance, in one of Warren’s folders I found a note Ben wrote to “Adam Smith” about The Money Game, declaring “I read your book with a great deal of enjoyment and with admiration.”

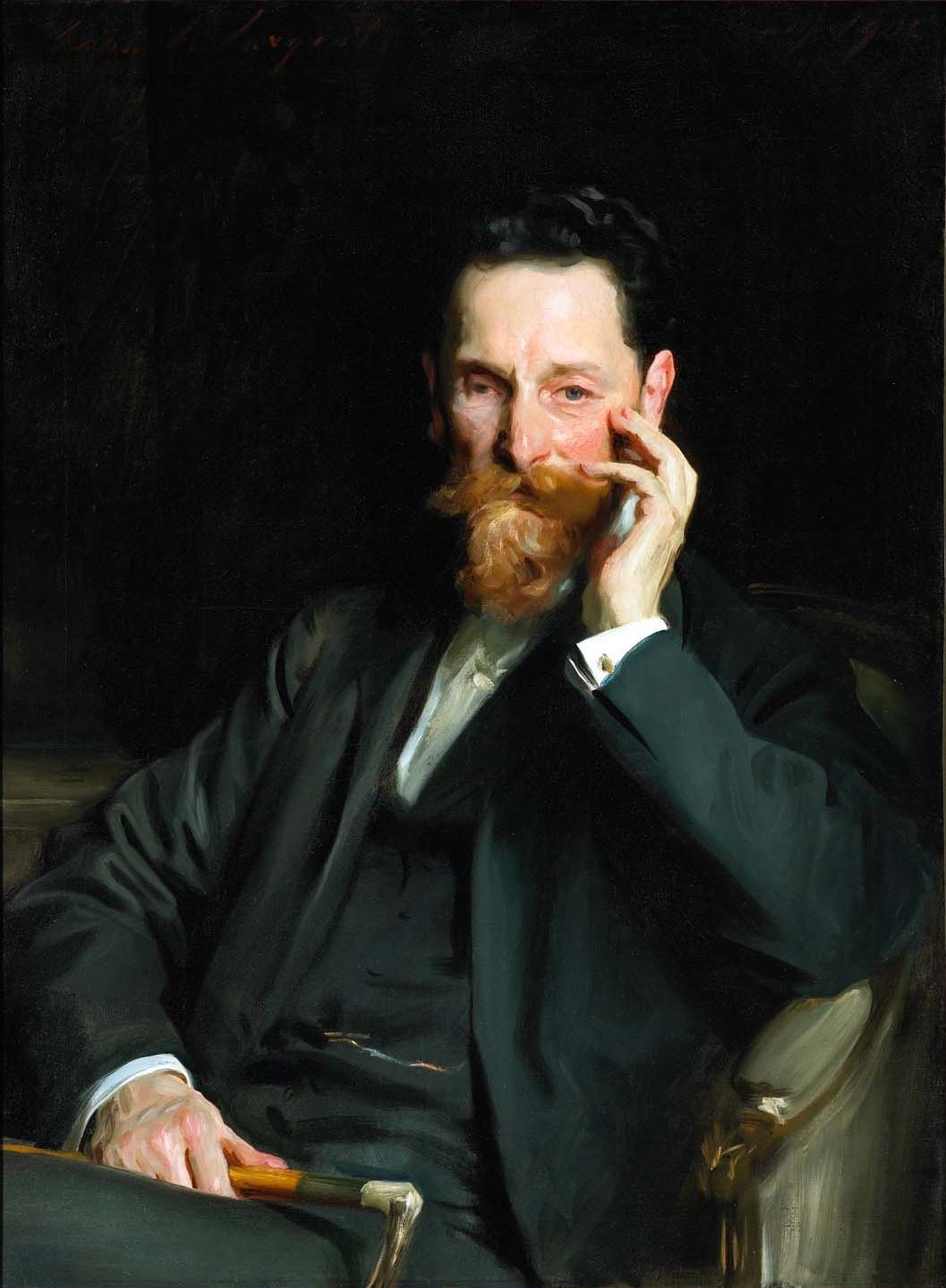

On our last day at Berkshire Hathaway, my husband and I readied the papers we’d chosen for the Benjamin Graham Archive, about two-thirds of Warren’s trove, for shipping. In yet another generous act, Warren had given the papers to me personally to donate to the Archive or not as I saw fit, and it made me happy to be contributing these documents, including a copy of Ben’s 1927 letter to John D. Rockefeller Jr. and some spirited correspondence between Ben and Warren that included a December 30, 1970 “Happy New Year” letter Ben wrote asking Warren questions pertaining to Ben’s revision of The Intelligent Investor, adding this endearing bit of Grandpa Ben gusto: “I’m gleefully considering a whole section on Ling-T.V—.” (Ling-Temco-Vought Inc.) I rejoiced in my role in establishing an archive of Benjamin Graham papers at Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library which the family will likely add to in future.

A smiling executive assistant boxed up the papers. “It’s been so nice to meet you in person,” she enthused. “You know, Warren talks about your grandfather all the time.”

“You mean, because he was expecting my visit?” I asked.

“No,” she answered. “I’ve been here twenty-five years. He talks about Ben Graham all the time.”