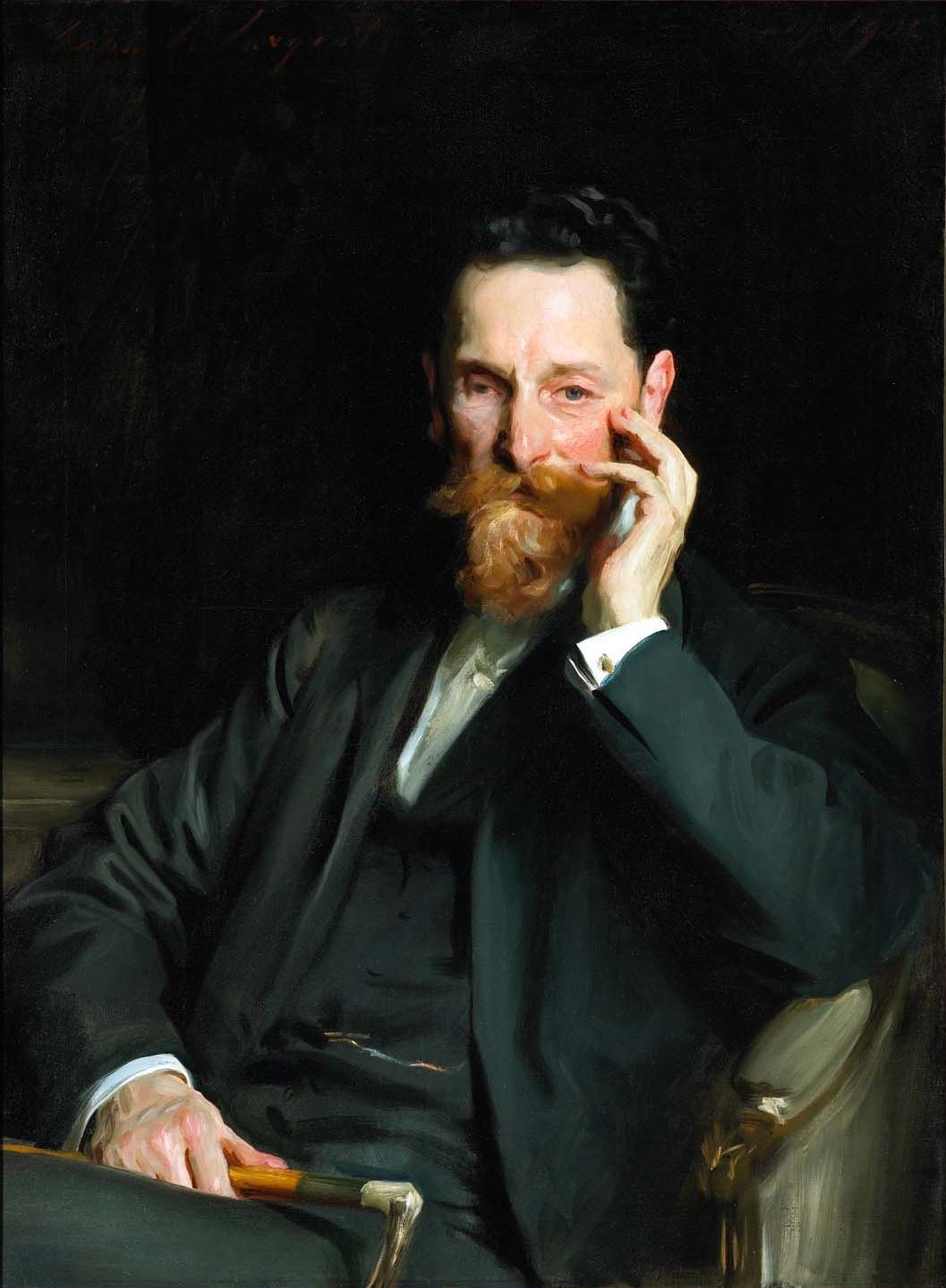

While Benjamin Graham spent the summer of 1910 toiling on a farm, he pinned his hopes on newspaper mogul Joseph Pulitzer as his future benefactor. This portrait of Joseph Pulitzer, painted in 1905 by John Singer Sargent, conveys the power the man held in Ben Graham’s mind. That spring, shortly before Benjamin Graham turned sixteen and graduated third in his high school class, Ben took the exam for prestigious Pulitzer Scholarship. Most graduating seniors make their college plans in advance, but Ben Graham had no money for tuition. All through the long days of arduous farm labor, my grandfather dreamed of winning a Pulitzer Scholarship.

Terrific News

One day that summer, Ben received a thrilling letter from his brother Victor. Victor wrote from New York City to tell him “exciting news”—the news that Ben had scored exceptionally well on the scholarship examination.

“‘Hurrah, Hurrah! You’ve won, you’ve won! You’re seventh on the list!’” –Ben’s brother Victor

In modern-day America, high school seniors—especially outstanding students like Ben—can apply for a wide gamut of scholarships, financial aid, and school loans in order to be able to afford college. In 1910, Ben Graham apparently knew of only one option: the Pulitzer Scholarship. Contestants from every public school in greater New York sat for the exam, and the top scorers won a chance for a scholarship.

Ben reveals fascinating details about this period in his autobiography, Benjamin Graham: Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street, but he avoids disclosing his reaction to Victor’s letter. I can imagine his elation. My grandfather must have envisaged that his life was about to change. Ever since his father, Isaac, died when Ben was eight, he’d aspired to filling his father’s shoes as the prime family earner. He longed to outshine his brothers and prove his worth to his mother. The “fabulous” Pulitzer Scholarship would enable him to attend Columbia College, live at home, and work to help support his mother, Dorothy. He believed that a prestigious college degree would pave the way to a job that offered sizeable earnings—sizeable enough to ensure that Dorothy would never endure financial hardship again.

“I took it for granted that the primary mark of success in life lay in large earning and large spending.”

Doubts assailed him. Ben regretted that he hadn’t placed higher than seventh on the exam.

“I would have felt really thrilled if I had ranked first, second or even third.”

Victor Roots for Ben

I’m pleased that Victor, the brother whom Ben described as “misbehaving” and “delinquent”, wrote Ben this celebratory letter—in verse! Poetry was Ben’s forte, and here was Victor, crowing about Ben’s success in iambic pentameter. Ben Graham had attested that he felt “ill-used” by his older brothers and suffered from their sharp words, but that seems behind them now. Victor took pride in Ben. He was rooting for Ben to go to college. This strikes me as big-hearted, because Victor and their elder brother Leon had had no such opportunity. Having earned high school diplomas, they worked at low-paying jobs. Because their uncle Maurice didn’t offer to help the boys go to college, and their unemployed mother required her sons’ financial support, Ben’s chance of attending Columbia rested on winning the scholarship.

Pulitzer Scholars

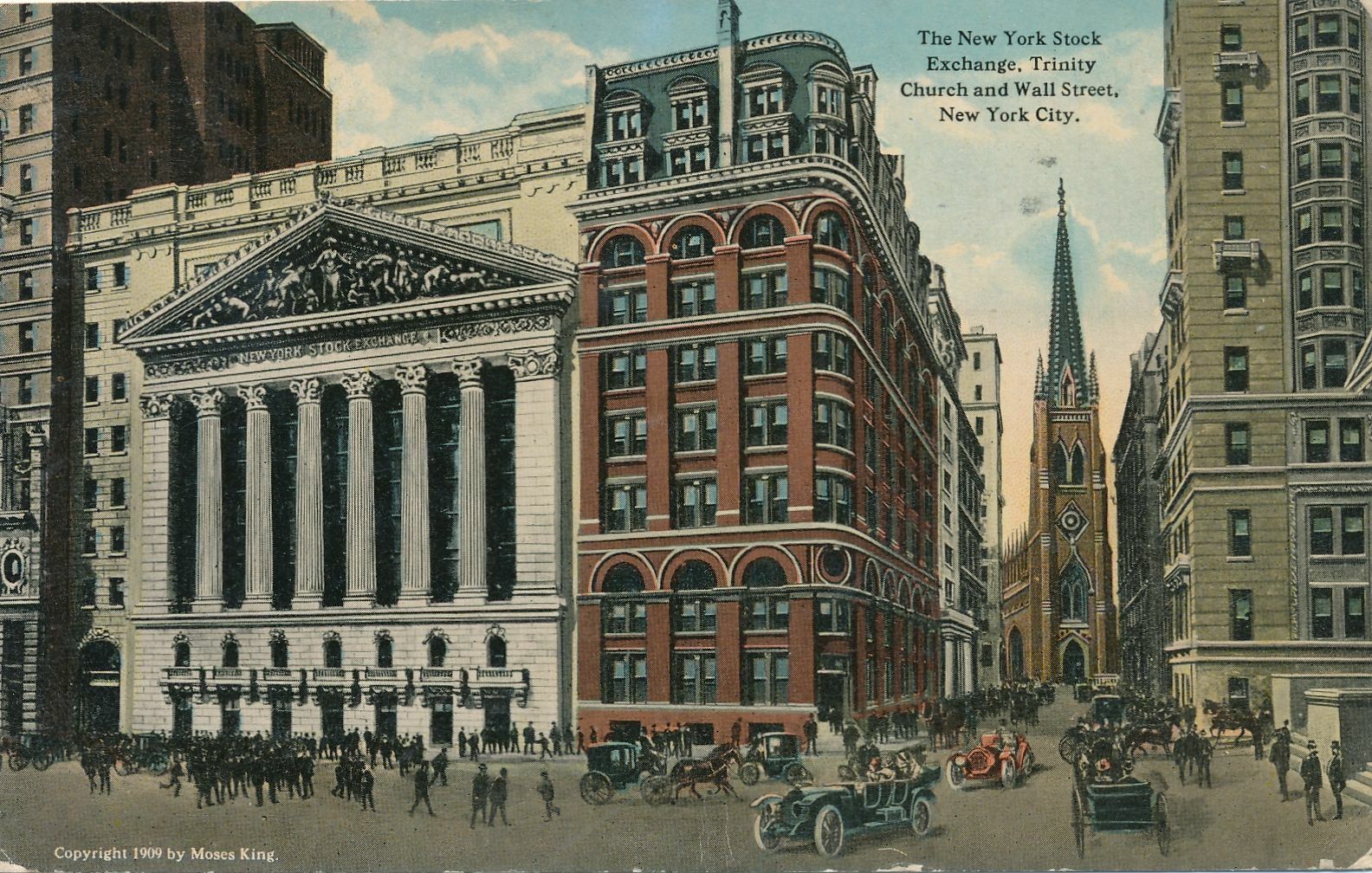

Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World and creator of the Pulitzer Prizes, established a scholarship fund for poor boys in 1889. Mr. Pulitzer’s 1911 obituary recounts that he “rose from poverty to wealth and power.” Time reports that “ten or twelve penniless New York City boys, mostly sons of immigrants” were chosen to be Pulitzer Scholars each year. (Girls had no such opportunity.) The Scholars received $250 a year for four years. If they went to Columbia College, tuition was free.

While completing his summer job at the New Milford farm, Ben reassured himself that he had a good chance of winning the scholarship.

“My position seemed eminently comfortable…I was in. The Pulitzer people duly visited my home and Mother had a pleasant interview with them.”

Learning of the official visit on his return to New York, Ben must have felt buoyed. Dorothy had made the most of her social graces when she visited him on the farm. No doubt she outdid herself with the Pulitzer committee. The visit served to confirm that the scholarship candidate was poor. Ben and Dorothy felt confident that the small Grossbaum apartment—located atop three flights of stairs and arrayed with threadbare furniture—proved that they lived in reduced circumstances.

A Big Moment, Misremembered?

The World Building—officially called the Pulitzer Building—on Park Row, New York, circa 1905. It was once the tallest office building in the world. Library of Congress, Courtesy of The Skyscraper Museum.

Ben Graham had one more hurdle to jump: an interview at the New York World Building in Park Place. How awed he must have felt when he approached the towering edifice—dubbed the Pulitzer Building—with its “elaborate façade of red sandstone and terra cotta” and gilded dome whose lantern served as “a beacon for ships at sea.”

“My examiner was no less than the editor-in-chief of the Pulitzer dailies, Mr. Alfred Harmsworth, who was also chairman of the Scholarship Committee under the will of the great newspaperman [Joseph Pulitzer]. Though I was nervous, Mr. H. soon put me at ease, and I found myself talking with some animation about my interests and ambitions.”

My grandfather—known for his exceptional memory—apparently forgot that Joseph Pulitzer was alive in 1910, so “the will of the great newspaperman” was not yet in effect. Mr. Pulitzer had disappeared from public view, likely because he suffered from blindness and acute noise sensitivity. Joseph Pulitzer died a year later on his yacht. I’m curious whether my grandfather knew that he and Mr. Pulitzer had a lot in common. Joseph Pulitzer was a Jewish immigrant—like Ben—whose father had also died when he was young, leaving his family penniless.

I think my grandfather also misremembered his examiner’s name. Mr. Alfred Harmsworth edited only a single issue of Pulitzer’s New York Daily News, in 1901. In 1910, Alfred Harmsworth was far too busy in England to be working for Joseph Pulitzer in New York—busy purchasing The Times, taking the title of Lord Northcliffe, and reigning over his news empire like an early-twentieth-century Rupert Murdoch.

Ben Graham’s interviewer could have been Frank Irving Cobb, an editor who had a tumultuous relationship with his boss. Cobb worked as an editor for Pulitzer in 1910. This lively article divulges that Pulitzer fired Cobb multiple times, and it attests that Cobb assumed the position of editor in chief after Pulitzer’s death.

Decline and Fall

Setting aside what he forgot, Ben Graham remembers a great deal.

“When [my interviewer] asked me what was my favorite book, I replied with enthusiasm, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire which I had read from beginning to end. Mr. H. seemed greatly impressed, remarking that I was the first boy he had met who had performed that literary feat. The interview went off very well, I thought, and I found it hard not to appear cocksure of the result when I reported to my family.”

Broken Dream

Ben telephoned his interviewer’s secretary a week later, as he’d been instructed, to ask about his status. Ben Graham recalls the moment in his Memoirs: “’I’m sorry,’ came the businesslike answer, ‘but you were not chosen.’” Ben reeled from the shock, then asked whether a friend had gotten a scholarship. The friend had. Ben didn’t ask why he had not. Like at the train station where he blundered the previous summer, Ben was too bashful to ask a question on his own behalf.

“This was worse than a disappointment; it came as a devastating blow. All splendor and hope suddenly went out of my life…My mother and brothers seemed just as dejected as I by my misfortune and a great deal more indignant. How could their Benny—number 7 on the list—have been passed over, while others far below his standing…were chosen?”

Louis XVI Settee circa 1890, with heavily weathered upholstery. Not the Grossbaums’ couch. Photo courtesy of gigimarieinteriors.com.

Ben’s mother blamed the furniture. Their badly worn Louis XVI couch and chairs, mementos of prosperous days when the boys’ father was alive, “still exuded at least a slight aura of luxury.” Dorothy thought that these once-elegant pieces gave the investigator the impression that Ben could afford to pay his own college tuition.

Ben Graham had his own wacky yet poignant idea. He believed that his interviewer detected a “secret deformity of my soul, and awarded the scholarship to someone purer and better than myself.” What was this “deformity” or flaw? “Something the French call mauvaises habitudes,” or bad habits. That’s the closest Ben could bring himself, penning his Memoirs at age seventy, to naming the healthy practice that most people engage in to relieve sexual tension—masturbation. He explains that “a combination of innate puritanism on my part and the hair-raising health tracts prevalent in those days had raised [this habit] to a moral and physical issue of enormous proportions.” Using indirect language, he reveals that at the time, he thought masturbation made him morally unfit to win a scholarship.

“This explanation was even more fanciful than Mother’s furniture theory.”

The mature Ben Graham realized that his youthful explanation was farfetched. In reviewing the history of masturbation, I find that the widely respected physician Dr. John Kellogg stigmatized it as leading to “loathsome crimes” in 1881, Freud associated it with addiction in 1905, and a Boy Scout handbook warned against its dangers in 1914. The shaming messages of his era rendered Ben so compunctious that he made a resolution to give up the habit.

Humiliation

What came next for sixteen-year-old Ben Graham? His mother persuaded him to enroll at the tuition-free City College of New York, or CCNY.

“I duly enrolled at City College but with a heavy heart. Why? Out of pure, unadulterated snobbishness. City College did not have as many brilliant professors as Harvard, Yale and Columbia… To go there, instead of to Columbia, meant the acceptance of inferiority, the admission of defeat.”

Ben didn’t want to attend college with students like himself: students who struggled to make ends meet, many of them immigrants with “low social standing” and “predominantly Jewish.” He judges himself, in his Memoirs, for his snobbery and then admits there was “some practical justification for this invidious conclusion.”

“A CCNY boy would be at some disadvantage in his professional and social career compared to a graduate of a first-rate college. This attitude reflected the general snobbishness of America in 1911; my own acceptance of these same distorted values intensified my feeling of humiliation.”

After Ben carelessly left his locker open and a thief stole two costly books, Ben Graham made an impulsive decision. He quit college and looked for a job. I quell my urge to criticize him. Millions of students get fine educations at public colleges. Not my grandfather. This was one of Benjamin Graham’s big moments on his way to big earnings. He had set his sights on Columbia because he viewed Columbia as a gateway to a high-paying job. A locked gate. But if Columbia was not to be, a substitute would not do.

Benjamin Graham, Teenaged Doorbell-Assembler

Ben Graham took a job that consisted of “assembling push buttons for electric doorbells.” To repeat the same manual operation from 7:00 a.m. until 5:30 p.m., day after day, became so tedious that he sat apart from the other five boys, reciting poetry. I’d call that creative but also antisocial and smugly superior. He calls it “communing with great poets.”

“I had a large repertory, including Gray’s ‘Elegy,’ all of the Rubaiyat, and even the first four hundred lines of the Aeneid. After a short time—perhaps two weeks—I was fed up with the monotony of those push buttons and looked again through the “Boy Wanted” section of the Sunday Times.”

Benjamin Graham, Teenaged Machine Shop Mechanic

Ben found a job at the Loeffler Telephone Company, which manufactured switchboards, telephones, and all the wiring required by new apartment buildings under construction on streets such as Park and Fifth Avenues. To “cut, drill, grind, shape and assemble” the parts, Ben learned to operate “hand tools and power-driven machinery,” including lathes and buffing machines. He worked from 7:30 a.m. until 6:00 p.m. and his long subway ride meant he barely made it home for dinner at 7:00.

My grandfather became interested in the inner workings of the telephone systems he was building. I smile to think how his life—and maybe our radios, TVs, and calculators—might have turned out differently if he’d stuck with his interest in electrical inventions.

“Soon I was studying the elaborate blueprints that were used in the installations. My great day came when an electrical contractor called up, during Loeffler’s absence, hurriedly asking to have some intricate difficulty in the wiring system cleared up—and I was able to explain it to him by looking at our copy of the blueprints.”

Dean Keppel Enters Benjamin Graham’s Life

In April of 1911, Ben Graham wrote to Columbia stating his wish to reapply for the Pulitzer Scholarship for the following academic year. Frederick P. Keppel, dean of Columbia College, replied with a mysterious note.

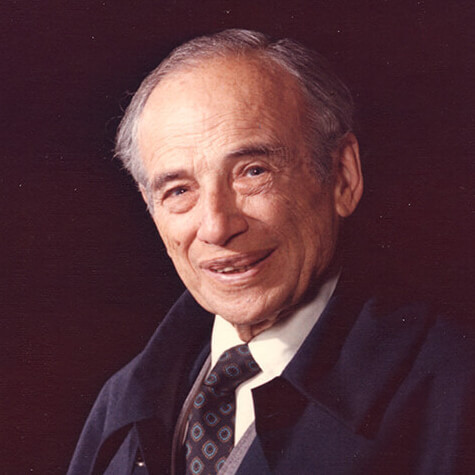

Frederick Paul Keppel, Dean of Columbia College from 1910 until 1918. Courtesy of Century Association Biographical Archive.

“He had a matter he would like to discuss with me at some convenient time. Would I make an appointment with his secretary?”

Ben described his work schedule to Dean Keppel’s secretary over the telephone and offered to leave work an hour early. The dean invited him to his home “the next day, a little before six o’clock.” Ben was intrigued and baffled.

“I cleaned my grimy hands as well as I could with grease solvent, took the West Side subway from Fulton Street to 116th Street, and walked over to the dean’s residence… With a thumping heart I rang the bell.”

The dean’s wife escorted him upstairs to a study with a crackling fire. Mr. Keppel strode in, “a tall, handsome, well-tailored man who combined a businesslike manner with a charming smile.” Benjamin Graham and Frederick Keppel drank tea. Then Mr. Keppel admitted that he and his staff were “frightfully embarrassed.”

“‘The fact is, Grossbaum,’ [the dean] continued, ‘you won a scholarship here last year but we didn’t give it to you.’”

The registrar’s office had mixed up Ben with his cousin, Louis Grossbaum, who had the same last name. (Ben’s family would change their name from Grossbaum to Graham in 1914.) Louis was already attending Columbia College on a Pulitzer Scholarship. The registrar’s office “couldn’t give the scholarship to a boy who already had one, so they gave [Ben’s] to the next fellow in line.”

A Life-Changing Moment

Dean Keppel proceeded to make Ben an offer that changed his life. He told Ben he had won a “prize”—the Columbia Alumni Scholarship. Ben had scored the highest grade on the College Entrance Board Examinations of all the boys who didn’t receive Pulitzer Scholarships.

“If I still wanted to come to Columbia College, they could arrange to award me the Alumni Scholarship beginning next fall.”

At this big moment, a door opened. Dean Keppel gave Ben the chance to fulfill his dream of attending Columbia. Today, we recognize that the benefits of a top-tier college include education and networking. This relationship with Mr. Keppel would prove to be life-changing. Dean Keppel didn’t forget the mistake he and his college had made. He didn’t forget Ben. Three years later, when Ben was about to graduate Phi Beta Kappa and second in his class at Columbia, he needed a job that had the potential for high earnings. Dean Keppel made up for his mistake by recommending Ben for that job. Stay tuned to my blog and I’ll tell you all about it.

Ben rushed home “in great excitement.” His brothers and mother joined him in “boundless rejoicing.” They saw this triumph the way Ben did—as his ticket to big earnings. They were counting on Ben to lift them out of poverty. When he was younger, he’d experienced their treatment of him as deeply wounding. Now that Ben was almost seventeen and college-bound, they’d become appreciative and supportive of him. That his family’s approval rested on Ben’s earning potential saddens me. He’d worked after-school jobs since he was nine, always giving his wages to his mother. They knew he’d be generous with them in future.

Dorothy’s longing for her sons to deliver her from financial need had profoundly affected Ben. Her longing sparked Ben’s competitive drive, to surpass his older brothers and become the family breadwinner. He even wanted to surpass his own father, an extraordinarily generous breadwinner who had once brought home big earnings—big enough to support his family of five in New York and “a veritable army of parents, uncles, aunts, and cousins in England.”

No matter how self-interested his family might have been, Ben delighted in sharing this jubilant moment with them. He recalls that his mother wept with joy. My grandfather ends his chapter with her loving quote:

“I’ll never be able to forgive them for causing so much heartache to my Benny.” –Dorothy Grossbaum.