When I was a little girl, I knew my Grandpa Ben was rich. He and his family and their awfully nice help person Lucy occupied a gorgeous mansion in Beverly Hills, while my family lived in an ordinary house near New Haven. The summer I turned six, my family was traveling in Europe and we happened to pass through Milan at the same time as Grandpa Ben. The chasm between my family and Grandpa Ben never seemed wider than on the day my mother took me to visit Grandpa at his Milanese palazzo. As we dressed in our nicest clothes, my mother’s ebullient mood lit up our drab hotel room. Ben’s eldest daughter, she adored her father and couldn’t wait to see him.

A taxi dropped us at a gate leading to a leafy garden, where, to my wonderment, real fish swam in a real stream. Trees towered over us, branches swaying, the susurration of leaves filling the air. Peering through this jungle, we could make out a resplendent façade. I cannot recall this palazzo’s name, nor can I find any photos of it, but its fish-stream and other adornments swim lucidly in my memory. I’m certain this place existed in 1957.

I’d never envied my grandfather more than I did at the moment we walked through his palace doors. Liveried pages bowed to welcome us. I stood awed by the splendor of the sweeping staircase and crystal chandeliers, which cast shimmering lights on the black marble floor. My Grandpa Ben lives here? I could hardly believe it. And I’d thought his stately California home, with its white columns and palm tree casting tropical shadows on an azure pool, was the height of extravagance.

Outside the palazzo doors, a Rolls Royce purred to a stop, discharging an elegant couple. They glided into the anteroom, followed by servants carrying a trunk and leather valises. Were these Grandpa’s friends, invited at the same time as us? Ahead I saw a wall of wooden slats much bigger than the ones in my mother’s rolltop desk where she kept bills. (When she paid the bills late, my father yelled at her.) As we approached the wall, I saw that the holes contained not bills but giant brass keys.

Then I understood. Grandpa was staying at an amazingly fancy hotel. I was disappointed he didn’t own the place, but still—what a thrill it was to be invited to see him in this sumptuous palace!

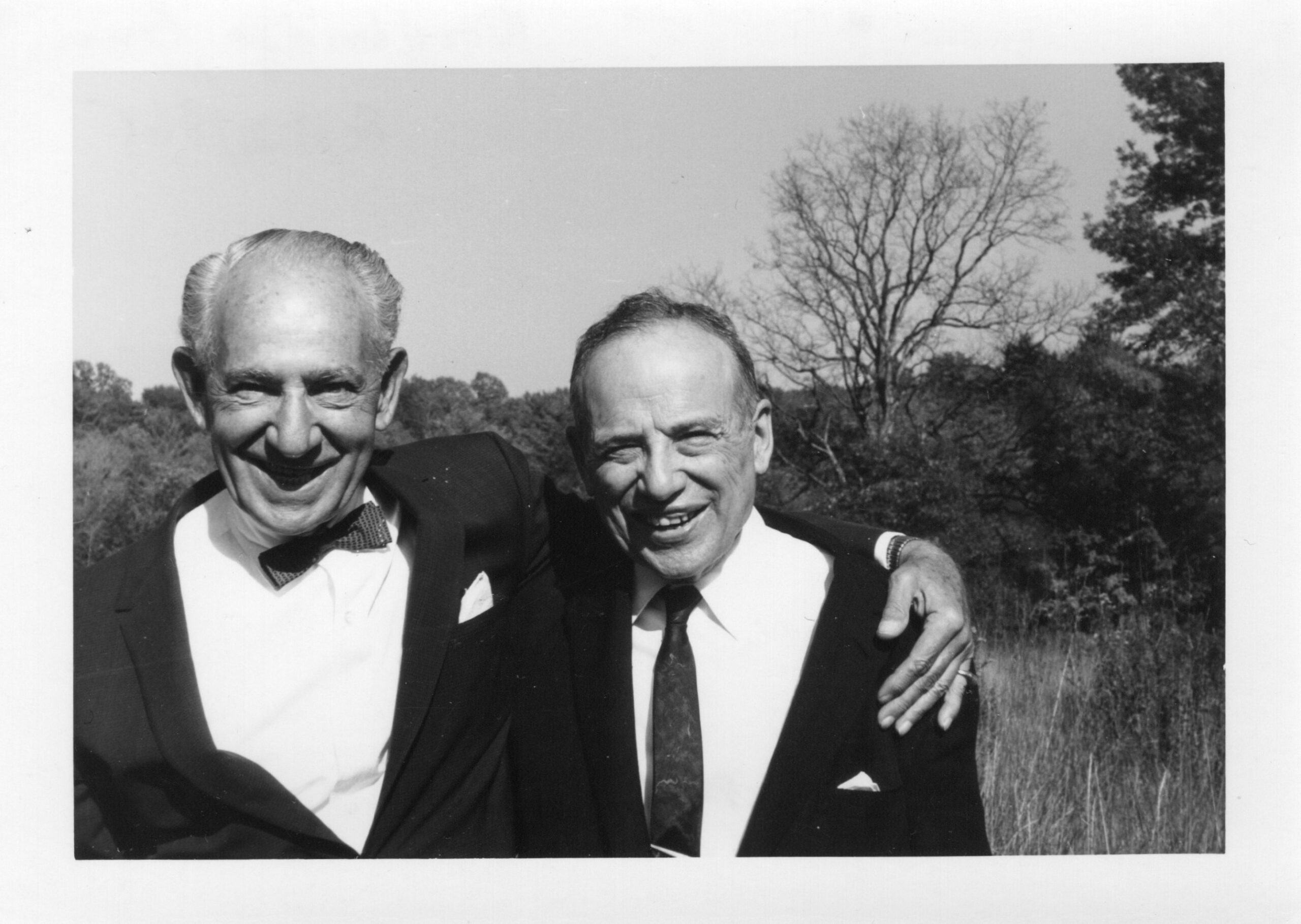

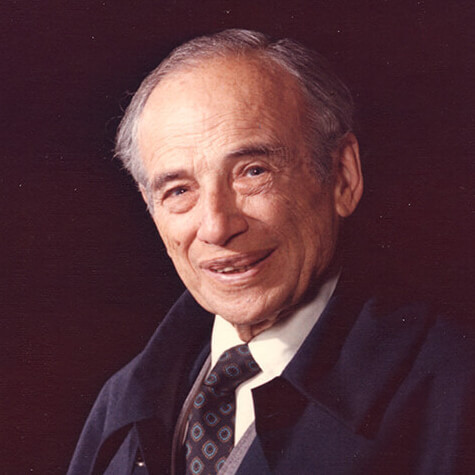

Up on a high floor, Grandpa greeted us with hugs and his broad smile. Grandpa let me slip off my pinching patent leather pumps and lounge on his bed’s silky coverlet. He showed me a button to push, whereupon red damask curtains parted to reveal views of terracotta rooftops and the Duomo’s towering spires. Each time I pressed the magic button, Grandpa and I exchanged a grin.

I remember my childish ideas about him as if it were yesterday. He belonged to a different, charmed species. Rich people were never insecure. They knew they were both loveable and loved. They knew that other people respected and admired them and wanted their company. Having wealth meant you never faced the loneliness of not being able to tell someone you loved your bad feelings and thoughts. It meant your father never yelled at your mom about late bills, because paying late fees wouldn’t faze him in the least. I knew my parents and I would never attain that happy state of harmony and well-being.

I call these beliefs “childish” without reflecting on their universality. Many people work, invest, and aspire to grow their wealth in hopes of obtaining well-being. Of course, anyone who experiences insecurity regarding food, water, shelter, clothing, transportation, and employment, strives to get more money. Those who don’t worry about survival needs, yet struggle at times to meet their expenses, also strive for more money. Those who don’t struggle financially—who can afford expensive homes and cars, services, and travel—still strive to get more money. Don’t we, as a culture, associate wealth with happiness, a greater sense of self-worth, social status, being admired and loved? Isn’t there some truth to the myth that a person with a yacht and a chef, who prepares miso-marinated black cod for guests on a private fishing trip, is less likely to be lonely than someone who fishes from a public pier and fries up her striped bass on a hot plate, in a room that barely fits one chair?

Ten years after my visit to the palazzo, Grandpa told me that Milan was the last place where he stayed at a luxurious hotel. However, while perusing his unpublished memoir, I discovered that he forgot to tell me about one more stay. He reports that, in June of 1961, he and his wife spent “a week at the fabulous Hotel de Paris at Monte Carlo.” At this majestic hotel (pictured above), Prince Rainier III and Princess Grace hosted their wedding breakfast in 1956, treating their guests to lobster, caviar and a six-tier cake that released two healthy turtle doves when Rainier’s sword cut the first slice.

Visiting Grandpa Ben in my teens in Aix-en-Provence and La Jolla was nothing like my awe-inspiring visit in Milan. Gone was the frisson of excitement at being invited to enter hallowed ground where only the rich can tread. His two homes were modest. He didn’t own a fancy car. What he did have was financial freedom. He could write me a check to cover my airfare and not note it on the check register. “Grandpa, did you forget to write it down?” (I was on a tight budget, and kept track of pennies.) He smiled and told me his banker would transfer funds from another account if his balance got low. Obviously, he had sufficient savings and probably investments from his career in finance, which ended in 1956, to ensure that he never had to worry about money. His life was no longer about investing, earning or spending.

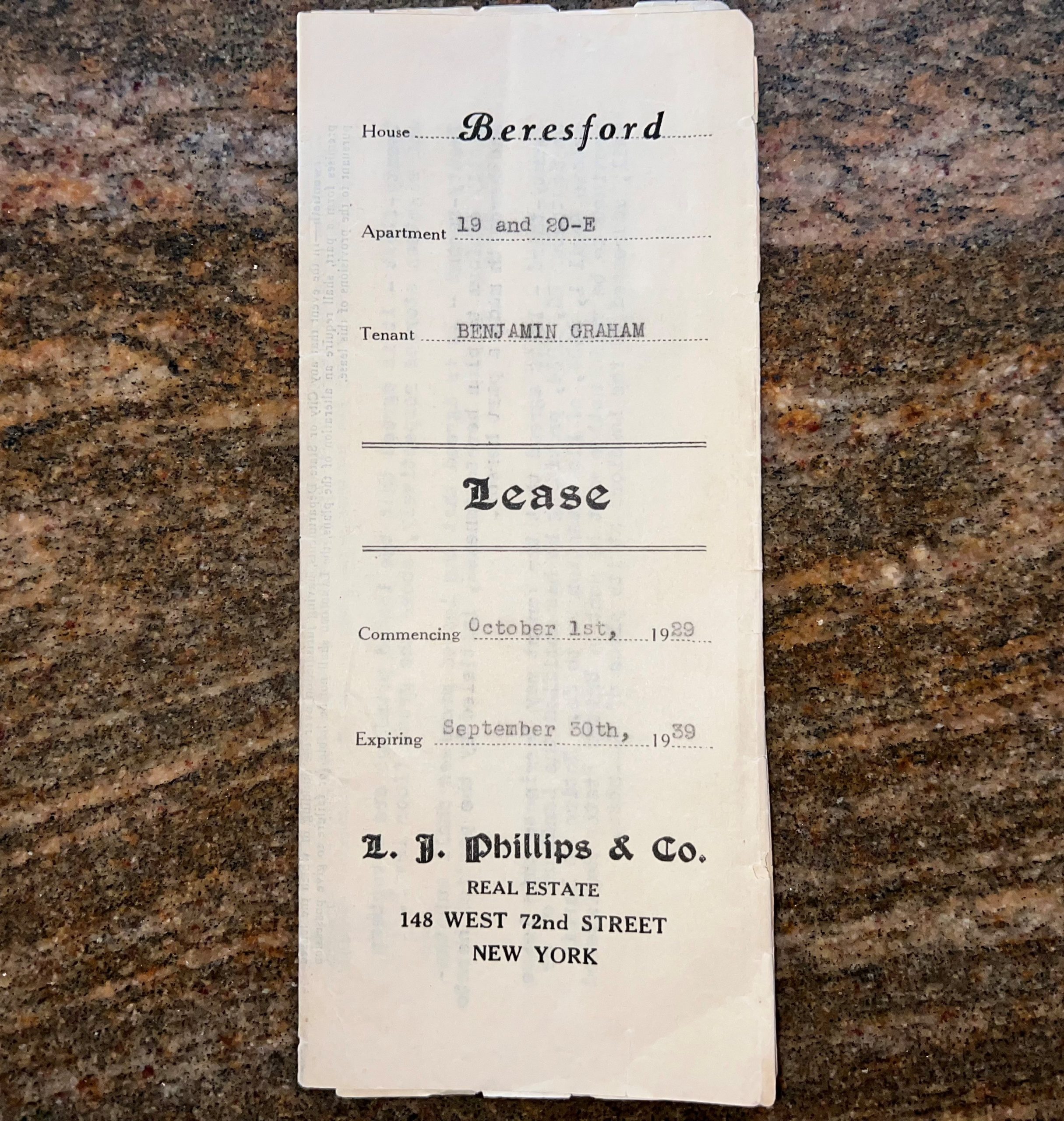

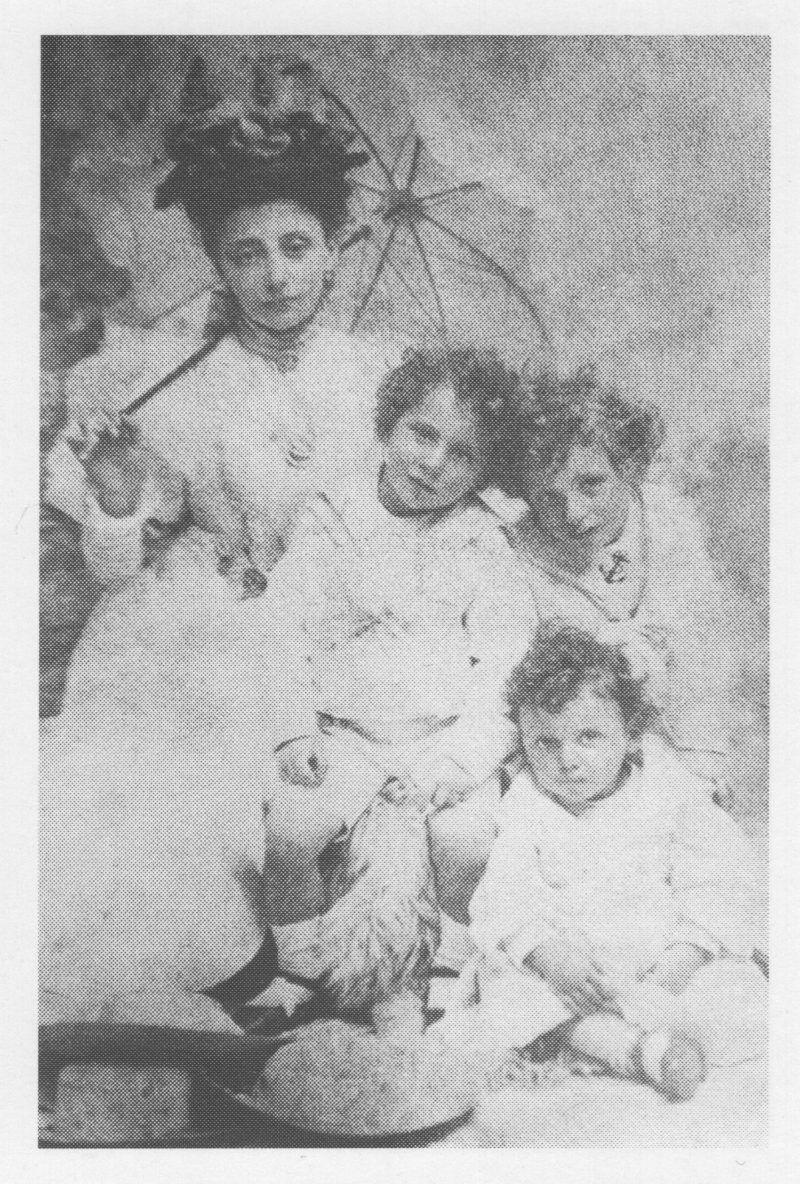

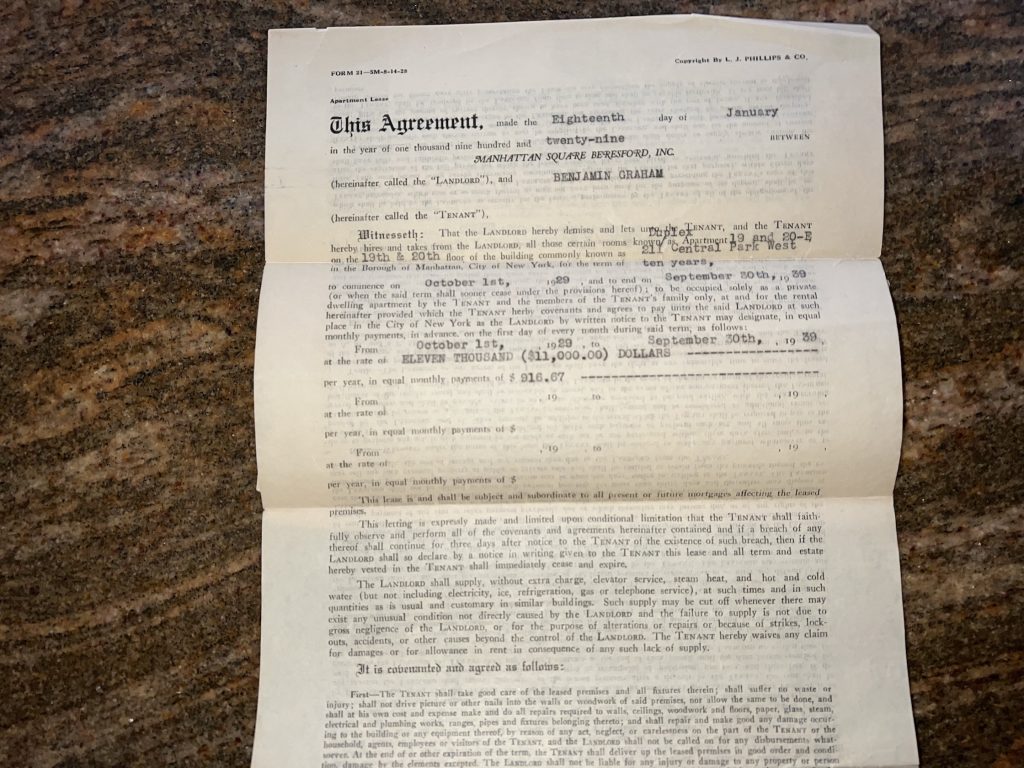

Nor was it about paying large bills, like the rent on the 19th and 20th floors of the brand-new Beresford (pictured above) for $11,000 a year. As he wrote in Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street, he leased these palatial quarters to house his family of five (Hazel would give birth to their third daughter in 1934) and “a troupe of servants.” My mother, Ben Graham’s eldest daughter, remembers playing with her siblings on its expansive terrace, with a view of Central Park and a hutch for their pet rabbit. The next-door neighbors, the Strausses, claimed that the Grahams were keeping guinea pigs and built an unsightly cast-iron wall between their terraces, cutting off the view. Always trouble in paradise, folks.

I found the yellowed contract for the Beresford tucked in a bundle of papers my mother gave me before she died. Shivers still go up my spine when I gingerly unfold the fragile, onion-skin pages Grandpa Ben held in his hand, nearly a century ago.

Savvy readers who notice the start date—October 1st, 1929—know what’s coming. Right after the Graham family moved into the Beresford, the stock market crashed. Grandpa Ben’s income plummeted. The terms of his fund—the Graham-Newman Joint Account—stipulated that he received no management fees, only a percentage of earnings, which dropped to near zero. Ben Graham’s first order of business was to reduce his costs. He arranged to sublet the Beresford apartment to Mrs. Marcus of Neiman-Marcus, and move his family into a “much cheaper” apartment. Regarding his “regal duplex” in the Beresford, he wrote:

“I was never really happy in that palace. I regretted the $11,000 rent and the ten-year contract as soon as they became realities. But in addition, the whole place seemed too large.” Ben Graham

No wonder that, for his last twenty years of life, he lived in two small homes, albeit in locales with cachet. Each summer and fall, he occupied a cottage in Aix-en-Provence, and in winter he migrated to a condominium in La Jolla, a coastal enclave north of San Diego, where his unexceptional rooms sported a distant view of the Pacific.

“It became my firm resolve never again to be maneuvered into ostentation, unnecessary luxury, or expenditures that I could not easily afford.” Benjamin Graham

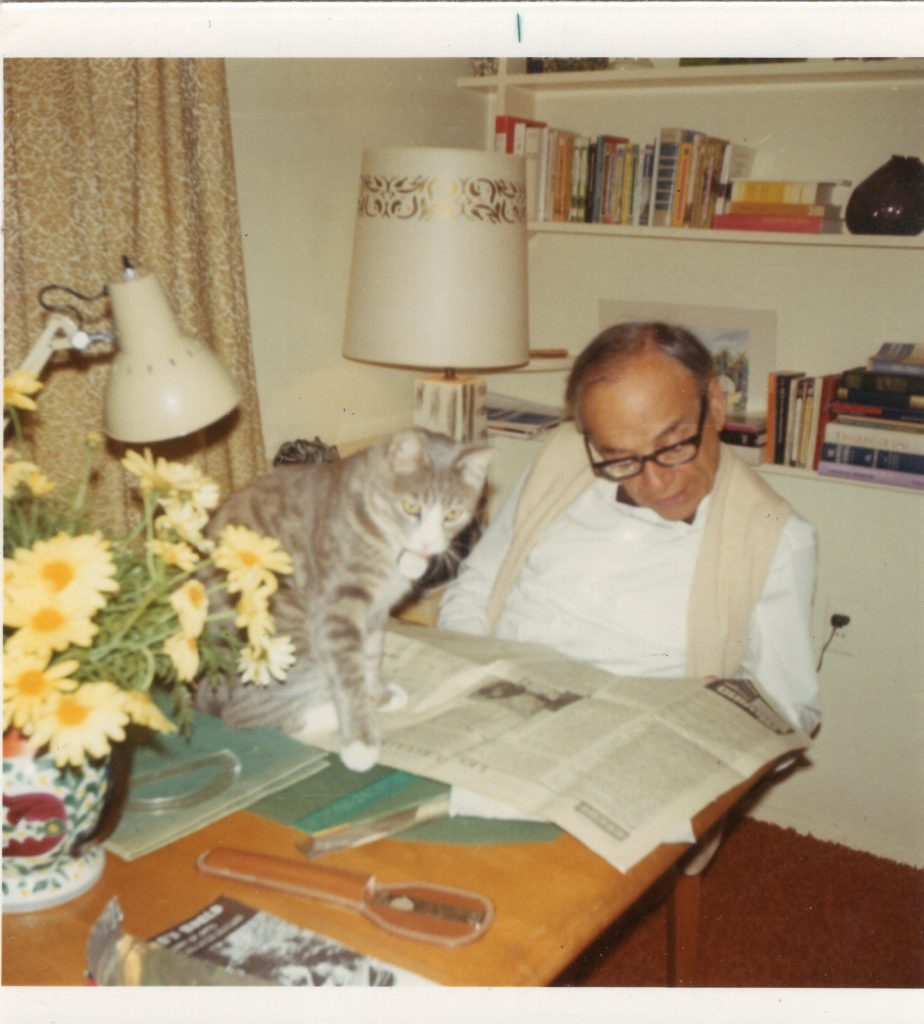

After he gave up palazzos, Grandpa Ben found tranquility in unimpressive quarters, enjoying rich moments with his newspaper and cat.

As a young adult, I gladly traded the thrill of opulence for the peaceful enjoyment of spending time with my late-blooming Grandpa Ben. I remember him working on one of his translations of classical Greek, his gray tabby cat Minet perched on his table. Each time Minet’s paw batted his jotting pen, Grandpa and I exchanged a grin.