I was sixteen the summer my Grandpa Ben invited me to join him on a cruise from Genoa, Italy to Istanbul and the Black Sea. On shipboard, he taught me his “pick-a-card-any-card” trick. After prompting a volunteer to pick a card and keep it out of sight, you had to go through the deck, simultaneously adding the card’s face value and suit. Grandpa had a way of rapidly moving his foot up and down to keep count. In sixty seconds or less, he would coolly name the missing card. Twice, the ship’s captain joined his admiring audience. I took many arduous minutes to do the same math that Grandpa Ben accomplished effortlessly.

Otherwise, Grandpa Ben kept his brilliant mathematical mind and his investment savvy under wraps, all through three weeks of spirited dining room conversations. If he still heard the siren call of the stock market, he might have scribbled calculations on a napkin or explained to me why Mr. Market was moody. Instead, Grandpa Ben waxed eloquent about Odysseus, who once sailed the same waters as our cruise ship, facing such dangers as the seductive nymph Calypso and the monster Scylla. No mythical creatures assailed us, just a missed opportunity for me. I passed up the chance to get to know my Grandpa Ben better during the cruise, spending most of my time with the bass guitarist in the ship’s rock band. Grandpa Ben didn’t seem to mind. He spent his days on a teak steamer chair, scrawling his memoirs in longhand on a sheaf of typewriter paper. He called his work in progress “Things I Remember.”

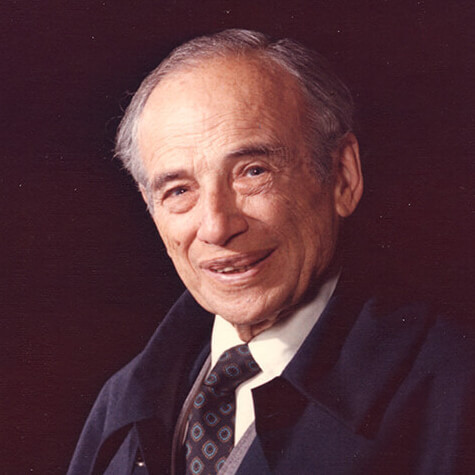

Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street was published in 1996 by Harcourt Brace, twenty-two years after Ben’s death and nearly thirty years after I’d been his companion on the cruise while he penned the manuscript. He had wanted “Things I Remember” to be published, and it took his adult children a long time to make that happen. When my mother handed me a newly minted copy, I felt a pang of loss. There was my Grandpa Ben, smiling at me from the cover. Suddenly I missed him terribly. I was excited to see what he had written on the cruise, when I could have asked him anything and asked him nothing.

I opened the book to the photographs, and found the adorable portrait of Ben (the youngest, age two) and his brothers Leon and Victor, shown at the top of this post. I was struck by the boys’ charming heads of curly dark hair, their white socks and girlish Mary Janes; my grandfather’s sweet vulnerable face appealed to me from a century ago. Grandpa Ben had a different response to the portrait, which had hung on a wall in his family’s home. He was embarrassed to be shown wearing “skirts,” a customary convenience for boys in diapers in 1896:

“But woe and indignity to me! Instead of the masculine short pants worn by my older brothers, I am captured for posterity in short skirts.” Benjamin Graham

Next I turned to Chapter One and enjoyed Grandpa Ben’s recollection of waking up, at age five and a half, to the news that he and his brothers were witnessing the turn of the 20th century. From this festive New York moment, Ben moves back in time to his birth in London, and forward again to the words his mother spoke to her littlest boy, circa 1900, that stuck with him all his life, ready to spill out—sharp as arrows—the moment he sat down to write “Things I Remember”:

“My mother was quite explicit on one point: I had grievously disappointed her by being a boy. After one still-born son and two other male offspring, her heart was set on a daughter. She had no hesitation in telling me that her first impulse was to ‘throw me out the window.’” Benjamin Graham

Grandpa Ben’s mother told him she had had the impulse to kill him at birth! That verbal blow must have struck Ben hard. A hundred years later, my great-grandmother Dorothy’s revelation gives me an emotional wallop. Her words call up my own childhood memories of feeling unworthy and unwanted. Ben Graham felt that, too; I’m sure of it.

Ben Graham’s “woe” at being “captured for posterity in short skirts” may have a deeper source than his embarrassment at being dressed in less masculine clothes than his brothers. The photo likely reminded him that his mother had had her heart “set on a daughter” and didn’t want him when she saw he was a boy.

He doesn’t report his reaction to his mother’s words, but, later in his Memoirs, he does report his “inordinate sensitivity to criticism” as a child and his “urge to escape any sort of censure by showing exemplary and pleasant conduct.” Describing himself in the third person, he writes:

“He must be invariably courteous, agreeable, patient; he must avoid conflicts of all kinds…”

That this extremely smart and sensitive boy would never allow himself to, say, show impatience or disagree with his mother or one of his brothers, signifies to me that he didn’t feel worthy of having others respect his feelings and opinions. Grandpa Ben’s sense of not being good enough, my mother’s, and my own, were likely linked—one generation passing this sense of inadequacy down to the next.

A retired RN/FNP, I forced myself to do a bit of research. Apparently, infanticidal impulses are not rare: the greater the mother’s lack of social and marital support, the more likely the thought of ending her baby’s life might flash through her head. Grandpa Ben’s mother Dorothy undoubtedly lacked support. Weary from caring for two toddlers during pregnancy, depleted from labor and delivery, Dorothy found herself with a mewling newborn, along with one- and two-year-old boys tugging at her. Who knows whether any of the in-laws with whom she lived in London were willing to lend a hand, while her husband Isaac was away all day at work. She must have felt very alone, exhausted, and overwhelmed. If her third child had been a girl, Dorothy would have taken solace from having another female in the family and a future helpmate.

What prompts a mother to tell her son about her preference for a girl, a preference so strong that she wants—for a dreadful second—to hurl her tiny son to his death? Whether intentionally or not, she gave my Grandpa Ben the message that she held all the power, and he’d better watch his step and meet all her demands.

After “throw me out the window,” Ben Graham adds:

“But to spare my feelings, she always added that she was happy she hadn’t done so.”

Always. She always added. Ergo, she told him this story more than once. No amount of reassurance would have convinced him he was safe and loved for who he was. Each time she repeated this story, she gave him the message that he wasn’t wanted by the person he depended on the most.

Ben Graham’s self-assured tone as he recounts his boyhood gives this reader the impression that he also felt that he mattered, or could matter to his mother, if he tried hard enough. If he was obedient and good. If he did household chores without complaint. If he eased his mother’s financial hardship—due to Ben’s father’s death—by taking after-school jobs. If he grew up and prospered, which in the early 20th century, only a son could do.

“[Mother] was ambitious for her sons, and in her darkest hours she was buoyed up by the confidence that in due time we would restore the family fortunes.” Benjamin Graham

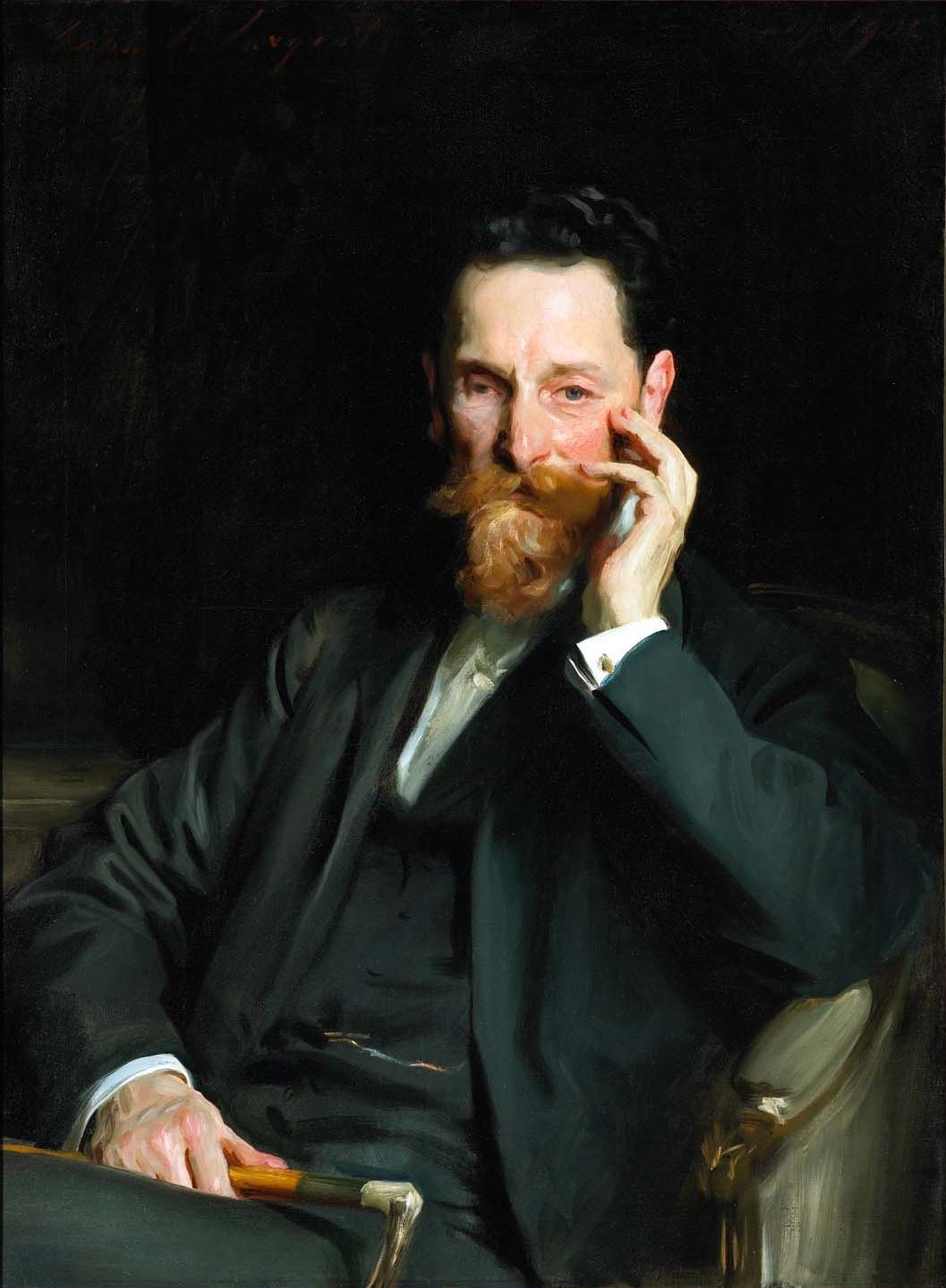

His mother not only freely expressed her demand that Ben and his brothers fill their late father’s shoes as breadwinner, and but also her “throw him out the window” impulse, which conveyed her view of Ben as worthless. Ben Graham put his mother’s conflicted expectations of him to work, letting them fuel his indomitable drive to prove his worth. We can see this drive in his rise on Wall Street, from board boy to inventor of value investing to millionaire. Then came the Crash of 1929 and its aftermath, when his Joint Account suffered a 70% cumulative loss. We see this drive in his six-year climb back to solvency. By 1936, Benjamin Graham was poised to start his fabled run as a fund manager—a run so legendary that Investopedia names him on their Top 5 All-Time Best Mutual Fund Managers.

He weathered the Crash. He weathered worse setbacks in his personal life. After each misstep and loss, Ben Graham forged ahead. The memory of his mother’s rejection of him—her desire to toss him away at birth—hurt him deeply. At the same time, this childhood wound taught him that he could move through hurt and keep going. He transformed that painful experience into iron resolve. He would show his family—and the world—that he had more to offer than anyone imagined. Unwanted and undaunted, he never stopped trying to prove to his mother that, by resisting “her first impulse,” she made the right choice.

Next: Benjamin Graham’s origin story, and the losses that shaped the man.