How did a nerdy math major like Benjamin Graham meet girls? My grandfather was a nineteen-year-old scholarship student at Columbia when he met a girl named Alda Miller. In the 1910s, Columbia was a men’s college. Barnard educated women at a separate location. Ben’s fellow students, and his fellow workers at his jobs, were all male.

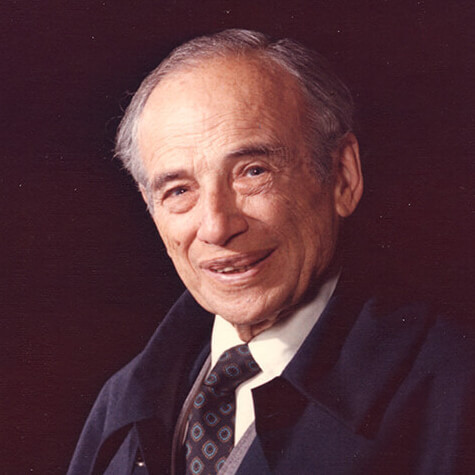

The Genius

According to Ben, writing in his posthumously published autobiography, Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street, my grandfather was “bashful with girls.” He had no sisters. Three girl cousins—Ethel, Helen, and Elsie, all Grossbaums—get a bare mention in the Memoirs, while Ben’s cousin Louis Grossbaum gets a major role. From first through twelfth grade, Ben never had girls in his class. I find it captivating to read his answer to my question—how did he meet girls?—writing in his early seventies, looking back fifty-plus years:

“My older brother Leon…had quite a way with the young ladies. He was self-assured and a good talker, given to quoting romantic poetry. From time to time he had more girls than he could handle, so naturally he turned some over to me. Indeed, I became part of Leon’s conversational stock in trade with his girlfriends. If he was to be believed, I was not only a genius—I was the genius.”

I always wondered how Leon and Ben impressed girls with Ben’s lightning-quick proficiency in math. Warren Buffett, in his 1976 tribute to his mentor Benjamin Graham, said, “I have never met anyone with a mind of similar scope.” Mr. Buffett goes on to laud Ben Graham’s “virtually total recall.” My grandfather understood that reciting the first four hundred lines of Virgil’s Aeneid in Latin wasn’t the way to a woman’s heart.

Mike Ross and his friend Trevor impress Nikki and Jenny with Mike’s math prowess, from Suits, Season 2, Episode 8.

How might Ben’s stature as a genius have played out? After seeing a similar scenario enacted in the engaging TV show, Suits (Season 2, Episode 8), I wrote this imagined scene with Ben, his older brother Leon, and a girl Leon wants to impress:

Girl, to Leon: “Ben’s your real brother? I thought you made him up.”

Ben (smiling, with gravitas): “Cognito, ergo sum.”

Leon: “Give us a break.”

Ben: “I think, therefore I am.”

Leon: “He thinks, therefore he spouts Latin, but he’s also, well, we can’t let this to go to his head—”

Ben: “Leon, stop.”

Girl: “Don’t stop.”

Leon: “My brother’s a genius.”

Girl: “You said that before. What kind of ‘genius’?”

Ben: “Tell her the joke, the one about—.”

Leon (interrupting): “Give him a math problem. A hard one.”

Girl: “Like what?”

Leon: “Like whatever pops into your head.”

Girl: “Say, 345 times 78 minus 23.”

Ben: “Twenty-six thousand, eight hundred and eighty-seven.”

Leon: “Voila.”

Girl: “Is he right?”

Leon: “Always.”

That’s likely how Ben met Leon’s girlfriend, who sold phonograph records at Abraham & Strauss in Brooklyn and let them listen to opera in the record booth. And that’s likely how Ben met Leon’s girlfriend, Sylvia Mazur—the sister of my future grandmother, Hazel Mazur. In later posts, you’ll get to know my inimitable grandmother.

Unlike the fictional hero of Suits, Ben Graham was lacking in social skills. He really had no experience talking with women. As for men, Ben tells us: “I made no close friends at Columbia. Was it because I was too busy studying and working?” Or, he asks, “had something happened to my emotional life that precluded male chums or cronies?” He thinks it had, and I agree. He distances himself from the very idea of close friends by calling them “chums or cronies.” He suffered emotional hurt in his relationship with his scary father, and his older brothers may have bullied him. These early traumas left him too guarded and reticent to develop close friendships, while his natural friendliness inclined him to make genial acquaintances all his life.

Romance Blooms

Ben never showed off his math talent for Alda Miller. He met her through a coworker, a boy named Lou Bernstein. Ben took a heavy course load at Columbia and worked when he wasn’t in class. Alda worked as a secretary in a law office that dealt with patents, where “the constant stream of technical material passing her desk served to widen her horizons.” She probably would have liked to widen her horizons further but in 1912, very few women went to college.

The Ninth Avenue El near 14th Street, circa 1914. Photo courtesy of the Bain Collection, Library of Congress.

“Our romance budded very quickly. Soon I was meeting her every day at the El station on our return from work.”

In her parents’ backyard, Ben and Alma would sit together on a tree swing.

Old vintage garden swing hanging from a tree. Photo by dreamstime.com.

First Kiss

“I remember one lilac-scented evening when I sat next to her in the swing and talked some nonsense—I think about Kant’s philosophy. I felt her hand against my cheek, and then it seemed to be turning my face more and more imperiously toward hers. It took me much too long to fathom that she wanted me to kiss her, but even the dullest wits catch on at last.”

I smile at this picture of my grandfather swinging with Alda, talking about Immanuel Kant. I would bet that Alda wasn’t much interested. Some rank Kant as the most difficult philosopher to read. I’m glad to be able to glean a scintilla of meaning from one Kant quote: “We see the world and things not as they are but as we are.”

Forbidden Desire

Benjamin Graham goes on to confess the conflicted feelings that kiss elicited.

“We were definitely in love. It was a delicious and disturbing period. Every time we met, Nature urged our bodies to unite; but they never did, because that wouldn’t have been respectable, and we were both highly respectable. There were, however, some experiences in the Miller hammock whose details the reader must imagine, though we remained virgins. But I, at least, felt ashamed. In some irrational way, I resented Alda’s physical power over me.”

I’m struck by how authentic my grandfather’s voice sounds in this passage. By “delicious,” I think he means the kissing and amorous touching “whose details the reader must imagine.” By “disturbing,” I think he means his moral scruples and guilt over feeling desire. He came of age at a time when many young adults felt ashamed of their healthy sexual urges, because their era’s moral code dictated no sex before marriage. Writing in his seventies, he assures us that they “remained virgins.” In tandem with the “disturbing” aspects of sexual tension, he must have been subject to the vulnerable emotions that first love engenders.

His “Laura” Inspired Ben to Write Love Sonnets

At one point in his college career, Ben took a half-time job as a “checker of waybills” that he found “terribly monotonous.” He began “writing sonnets” as an “antidote against boredom.”

“I tried to write a different [sonnet] each day, completing the first draft in the morning and polishing it throughout the afternoon. Most were love sonnets inspired by my particular Laura of the period—whose name was Alda.”

What does he mean by “his particular Laura of the period?” He’s referring to Laura, the beloved of the fourteenth-century Italian poet Petrarch. Petrarch wrote 300 sonnets expressing his love for her over the course of twenty years. Scholars believe she was Laura de Noves, a married woman with children. Petrarch’s unrequited passion for Laura, immortalized in his sonnets, became so famous that numerous artists painted her portrait, including nineteenth-century German painter Anselm Feuerbach (whose depiction appears atop this post) and this luminous work of art painted by Leonardo da Vinci or one of his followers.

Petrarch’s Laura by Leonardo Da Vinci, or a 17th century copy of a lost original by a follower of Da Vinci. Laura holds a carnation and an apple, interpreted as “nuptial attributes.” Photo courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum.

In the Glow of Romantic Passion

Imagine my excitement when I found one of Ben’s sonnets among Warren Buffett’s papers. You may have read the story of my visit with Warren Buffett. Last spring, Mr. Buffett invited me to Omaha to go through his Ben Graham files and select documents of historical value to be donated to an archive of Benjamin Graham papers at Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. That’s how I come to hold in my hand this note from Estelle Graham—Ben Graham’s third wife and my Grandma Estey—to Warren Buffett.

Estelle Graham, Ben’s third wife and the Buffetts’ friend, wrote this note to Warren Buffett and attached it to the “Character Study” Ben wrote about himself in 1957.

Estelle addressed the note “Dear Warren” and signed it “Much love to you and Susie.” Estelle had an enduring friendship with Warren and his wife, Susie. Last April, Warren Buffett told me: “I admired Estey enormously.” I found Estelle’s note stapled to three pages, titled “A Character Study” and dated “May 1957.” That’s one year after my grandfather closed his Wall Street office, retired as a fund manager, and moved to California. On them, Ben had typed what Estelle calls “Ben’s own evaluation of himself,” written in the third person. On page three, Ben Graham writes:

“A poem came back to his mind that he had written as a college sophomore, in the glow of first romantic passion.”

Inspiration

As a brook slumbers, hushed its tinkling song,

By March’s icy cloak held prisoner,

My soul has music, too, that cannot stir,

Frozen to silence by a witless tongue.

But lo! the bar melts in the breath of Spring,

The water wakes into melody;

So by the warmth this new love sheds on me,

The bonds of speech are burst, and I may sing!

I’m moved to be able to read a sonnet sparked by Ben’s feelings for Alda. His poem’s two quatrains follow an ABBA CDDC rhyme scheme—neither the Petrarchan nor the Shakespearean sonnet form. The poem strikes me as flowery yet impersonal. Ben is a brook, slumbering in winter. He’s too frozen to flow or let loose the music in his soul. That’s a pretty accurate description of his remote and walled-off emotional state. Enter Alda, “the breath of Spring” who melts his ice and frees him to sing.

Not until I had regained a bit of equanimity after the thrill of meeting Warren Buffett did I realize I’d read the sonnet before. I found it in the Memoirs Epilogue, in “Benjamin Graham’s Self-Portrait at Sixty-Three.” Now that my detective work has revealed that he wrote it long before, when he was enamored with Alda, the poem shines brighter.

“Ben, Don’t You Love Me?”

I return now to Ben’s account of his romance.

“One Sunday afternoon amid a gathering of young people at the Millers’, Alda sat on my lap—an act which I adored in private but which made me feel ridiculous before all those friends. She asked, and not in a whisper: ‘Ben, don’t you love me?’”

That she sat on his lap in front of other people “made [him] feel ridiculous.” Ben the poet writes that, due to Alda’s warmth, “the bonds of speech are burst, and I may sing.” Had he ever “sung” or told her “I love you”? Had she asked for this reassurance from him before? He doesn’t say.

“‘Of course I do, dear,’ I whispered.

‘But tell me that you love me more than anyone else in the world. Tell everybody’, she insisted, her voice almost strident.

‘Yes, yes, Alda, I love you more than anyone else.’”

Ben grew up in a family where no one said, “I love you.” Benjamin and his mother, Dorothy, did not express fond feelings for each other, neither with words nor hugs and kisses. If you scroll down to the end of “Benjamin Graham: Big Moments on the Way to Big Earnings (#13),” you’ll find a loving sentence uttered by Dorothy. It’s a far cry from “I love you.” We saw how Dorothy kept the precious cookies she baked all for herself, hiding them among her lingerie to keep her sons away. For Ben, “I love you” may have been taboo.

Sharp Desires, Sudden Breakup

Ben’s response to his unstated but acute discomfort was to write Alda a “long sensible letter.” He explained that he was still a college student and likely would spend three more years in law school. (He applied to law school, received a scholarship, and turned it down, mostly because of his next girlfriend—my grandmother.)

“How could we think seriously of love, if marriage had to be deferred until I could support her in a proper fashion?”

He goes on to say that he and Alda were becoming “more and more involved with each other.”

“Desires were sharpening that we had no hope of satisfying… She was so much in my thoughts and blood that I could not do justice to my college work.”

I think he’s exaggerating. He did exceptionally well in his courses despite long work hours and a distracting relationship. He completed four years of college in three years, graduating third in his class. The one bad grade he reports—a C- in History of Western Europe—occurred in his freshman year, before he met Alda.

The mores that frowned on premarital sex simplified and complicated relationships between young people. With no birth control available, this stricture protected Ben and Alda from an unwanted pregnancy—a pregnancy that would have propelled them into marriage.

Understandably, Ben and his contemporaries found it terribly difficult to handle their feelings of attraction.

“After much argument and excuse, I announced my sad decision: we must end our romance immediately by a complete break. It was best for both of us not to meet again.”

Romantic Love in the Classics

What Ben knew about romantic love, he learned from reading the classics. He certainly knew about Paris and Helen of Troy, as well as Odysseus and Penelope, from Homer. In Memoirs, he says that while in college he compared Goethe with Euripides, so he knew about Faust’s Margaret. He tells Dean Keppel that he could read Horace and Catullus in Latin at home and didn’t need to study Latin at Columbia. He mentions Wuthering Heights, which means he was familiar with the love of Heathcliff and Catherine and their passionate longing to become whole by giving each other their all.

The only works he refers to when contemplating Alda are Petrarch’s sonnets, written for the unattainable “Laura.” Petrarch’s sonnets didn’t teach Ben how to navigate the troubles that follow on the heels of romantic passion. Modern-day young people get the chance to develop relationship skills—how to listen empathetically, repair hurt, set boundaries, work things out—from emotionally intelligent parents and peers, as well as from exposure to insightful books, television shows, films, and social media. Ben had no chance to learn these skills.

Having built a protective wall around his heart, Ben lived in a detached place where it was near impossible for him to connect with himself—his wants, feelings, needs, state of mind. Good relationships depend on us enlarging our capacity to do that very thing: to be connected with ourselves and our loved one at the same time. To see that loved one as a separate person who is different than we are. To see oneself as worthy, lovable, a good person who sometimes has a hard time, particularly with managing difficult emotions, and to regard our partner with that same friendliness and acceptance.

The Courage to Dive into Love’s Abyss

I marvel at the courage it took for Ben to dive into love’s abyss. He couldn’t see bottom, and he couldn’t steer to safety. A careful reading of the Memoirs reveals that he never mentions observing his parents show affection, speak endearments, argue, or make up. Whatever he saw, he saw through the eyes of a young child. His father died when he was eight. Since that life-changing event, he’d shared a home with only one couple—his Uncle Maurice and Aunt Eva. While Ben did his homework at the dining room table, his uncle “would berate my aunt for some foolish play” at cards. Ben had an inborn kindness and aversion to hurting other people that infused his spirit. He described his uncle “as ill-tempered and tyrannical as he was intellectually brilliant.” Ben had no wish to follow his uncle’s example of how to be a domineering male.

Ben’s brother Leon, whom he describes as “self-assured and a good talker,” became Ben’s role model for how to flirt. No one role-modeled how to stand up for yourself, how to honor your own needs as well as your partner’s, or how to be authentic and speak your truth. That’s why I think Ben Graham couldn’t imagine working things out with Alda. I’ll take a stab at trying on his behalf. “I’m a private person, Alda. You’re very special to me, but please don’t ask me to express my affection for you except in private moments.” I doubt he was able to acknowledge to himself, much less articulate, this need.

Ben’s mother Dorothy had told him she wanted to throw him out the window when he was born, because he was a boy and she wanted a girl. This threat shaped him. Benjamin Graham became the dutiful son who never stopped striving to show his mother he was worth keeping. He always obeyed his mother, abandoning his own needs in order to please her. He couldn’t say no to her, and he couldn’t say no to his girlfriend. Not knowing how to set boundaries, he felt his only recourse was to break up with Alda.

I’m grateful Benjamin Graham didn’t work things out with Alda. If he had, he wouldn’t have endeavored to win my grandmother against fierce competition. My mother and I and many other dear ones would never have been born. I admire my grandfather’s lifelong determination to learn how to love and be loved. How in the world would this brainy math whiz ever find a way to disassemble his wall and open his heart?