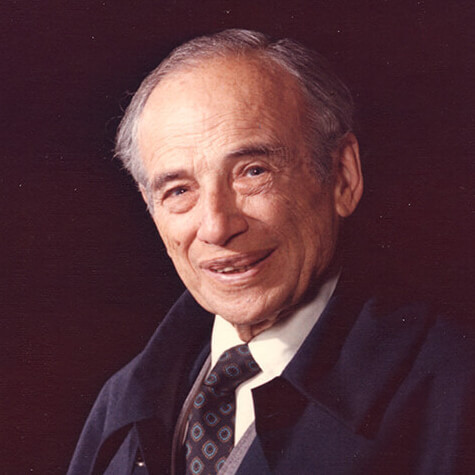

Benjamin Graham was in serious trouble. By mid-1932, the Dow had plummeted eighty-nine percent from its 1929 peak. Graham had lost seventy percent of both his personal wealth and the value of the assets in the Benjamin Graham Joint Account. Yet compared to the fiscal collapse facing thousands of his contemporaries such as the man pictured above, Graham remained relatively fortunate. He still had an apartment, an office, and enough capital to provide for his family.

Crucially, he remained fiercely determined to rebuild his hedge fund and restore it to its pre-Crash stature. Under the terms of his unusual compensation agreement, he wouldn’t earn a penny in fees until he had fully repaid his investors’ losses. How did my grandfather claw his way back from financial ruin to lasting prosperity?

Value Investing Saved the Day

Ben Graham put into practice the enduring principles of value investing he had uncovered. Targeting deeply undervalued stocks—those priced below their liquidation value and often trading for less than their net assets—he focused on companies so overlooked that some were selling for less than the cash they had on hand. Although he didn’t know it at the time, the Dow Jones Industrial Average would go on to triple between 1933 and 1935. That meant that having invested heavily in 1932–33 and, true to his philosophy, held onto these bargains, his returns would be outstanding.

Ben Graham Utilized Human Calculators

How did Ben Graham find these deeply undervalued stocks? Financial journalist Richard Phalon wrote a lively account of how Ben Graham did it in his chapter “Value Avatar: Benjamin Graham,” which appears in his book Forbes Greatest Investing Stories. After the Crash, Ben Graham continued to teach his class in Advanced Security Analysis at Columbia School of Business.

“Now, suddenly, after the Great Crash that had put him in such hot water, value was everywhere and going begging. Ben set a cadre of his students to matching market prices and values for all 600 industrials listed on the New York Stock Exchange. This was foot slogging work in the pre-calculator, pre-computer age, but the results were startling: One out of every three of the 600 could be bought for less than net working capital. More than 50 were selling for less than the cash (and marketable securities) they had in the bank.” Richard Phalon in “Value Avatar”

Richard Phalon discloses his source for this information: “A series of three articles for Forbes summed up what [Ben Graham] had learned from the Great Crash.” The articles also “helped to showcase the extraordinary quality of the training he gave three generations of up-and-coming money managers at the Columbia Business School, including such reigning Grahamites as Warren Buffett and the Sequoia Fund’s Bill Ruane.”

Sure enough, I was able to find that in Ben’s first article “Inflated Treasuries And Deflated Stockholders,” published in Forbes on June 1, 1932, he does indeed reveal how he found those undervalued stocks.

“A study made at the Columbia University School of Business under the writer’s direction, covering some 600 industrial companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange, disclosed that over 200 of them—or fully one out of three—have been selling at less than their net quick assets.”

I read on, only to find that a crucial piece of the article is missing.

“Over fifty of them have sold for less than their cash and marketable securities alone. In the appended table is given a partial list, comprising the more representative companies in the latter category.”

The appended table does not appear. Phalon apparently found it, because he details some of Ben’s and his students’ outstanding finds.

“Montgomery Ward, for example, was trading for less than half of net quick assets. For $6.50 a share, you got $16 in working capital and the whole of this great retailing franchise—catalog business and all—for nothing. With issues like American Car & Foundry and Munsinger, $20 and $11 would bring $50 a share and $17 a share, respectively, in cash alone. The rest of the businesses—bricks, mortar, machinery, customers, and profits—was a free ride.” Richard Phelan in “Value Avatar”

Where can I find that appended table? I ask chatgpt.com, which can’t produce it for me but mentions a source that “did not allow viewing the table.” I recognize that source—a book I recently acquired from Ben’s son Benjamin “Buz” Graham Jr., my Uncle Buz, who passed away last spring. The book, Benjamin Graham: Building a Profession, edited by The Wall Street Journal’s personal finance columnist Jason Zweig, contains a collection of Ben’s early writings, including the 1932 Forbes articles and the missing table.

Table 1: Stocks That are Selling for Less Than Their Cash Assets, in Benjamin Graham: Building a Profession, edited by Jason Zweig, CFI Institute & McGraw-Hill, 2010

Ben Graham Shared His Investments Secrets

Right away, I’m struck by Ben’s generosity. In Blog Post #20, I observe that Benjamin Graham didn’t keep his money-making strategies to himself. On the contrary, “he offered his methods to his bosses, his clients, and his students at Columbia Business School.” Some students, professionals working at rival firms, rushed from class to ride the subway to Wall Street and buy the undervalued stocks Ben had just analyzed in his lecture.

Now I’ve learned that Ben shared his stock discoveries with Forbes readers as well! What bighearted generosity—especially considering that Forbes had an estimated circulation of over 80,000 in 1932. I’m genuinely moved by Ben’s commitment to helping others find financial security—a mission that defined so much of his life’s work. That same impulse fueled his relentless refinement of investment principles and inspired him to share his insights—clearly and accessibly—through books, articles, and nearly three decades of teaching at Columbia Business School from 1928 to 1955.

“Selling America for 50 Cents on the Dollar”

Title page of Ben Graham’s first article in Forbes published in 1932, Benjamin Graham: Building a Profession, edited by Jason Zweig, CFI Institute & McGraw-Hill, 2010.

Ben’s subtitle brings a smile to my face. He injects a light touch of humor into the bleak landscape of the Depression economy.

Lessons of the Great Crash and Depression

Title Page of The Intelligent Investor, First Edition, published by Harper & Brothers in New York, 1949. Benjamin Graham wrote a comment in his own handwriting—changing his title at Columbia from Lecturer to Guest Professor. You can also see the epigraph Ben chose from the Aeneid.

What did Benjamin Graham learn from the 1929 Crash and ensuing Depression? Thrumming with excitement, I open the book that holds the answers, a worn copy of the first edition of The Intelligent Investor, published in 1949. This book, given to me by Benjamin Graham’s youngest son, my late Uncle Buz, also feels like a gift from Grandpa Ben himself. Why is that? Because my grandfather penciled annotations throughout the book, his oft illegible scrawl detailing editorial changes he wanted to make, perhaps for the second revised edition he would publish in 1959.

The margins of Benjamin Graham’s 1949 copy of The Intelligent Investor are filled with his handwritten notes—a book that now resides in the library of his granddaughter who authors this blog.

I turn to the chapter that promises to reveal Ben’s insights into the Crash and its aftermath: Chapter 11, aptly titled “The Investor and Stock Market Fluctuations.” I’m curious to see how he draws us into his view of Wall Street, one in which the true investor endures market ups and downs with calm resilience, while the speculator feels pain each time prices “fall into the abyss.” Let’s take a look at his opening paragraph.

“This chapter will be devoted to an effort to delineate the proper attitude which investors should take in the matter of price fluctuations in common stock. It is becoming increasingly difficult to attain that peculiar combination of alertness and detachment which characterizes the successful investor as distinguished from the speculator. Intelligent investment is more a matter of mental approach than it is of technique. A sound mental approach toward stock fluctuations is the touchstone of all successful investment under present-day conditions.” (page 22)

I love how Ben weaves his own personality into this passage. He published this book in 1949, long after he recovered from excruciating Depression-era losses, yet he sounds so Ben-like: sensible, smart, measured, and emotionally distant. The average reader would have no idea that Ben himself lived through post-Crash hell. The wall Ben erected in his youth to protect himself from emotional hurt had made him a remote husband and father, an amiable man with a ready smile and many friendly acquaintances but no close friends.

Keeping Your Balance When the Market Doesn’t

We see how Ben made his emotional distance a keystone of his investment strategy. Don’t ride the roller coaster, he’s saying. Don’t feel good when prices go up and bad when they go down. He speaks from experience, having once hopped aboard that roller coaster when he was twelve. That’s when his widowed mother invested her last $5,000 in U.S. Steel, unaware she was being duped. Ben would check the financial pages for the stock price daily and crow the price to his mother whenever it rose. Little did he know that his mother would lose every penny in a bucket shop scam, which used the Panic of 1907 to declare her account at zero, pocketing her entire investment for its crooked fraudsters.

In the depths of Chapter 11 of the first edition, Ben Graham lays out the essential qualities of the intelligent investor.

“He must deal in values, not in price movements. He must be relatively immune to optimism or pessimism and impervious to business or stock-market forecasts. In a word, he must be psychologically prepared to be a true investor and not a speculator masquerading as an investor.” (p. 36)

In other words, he’s saying: “Don’t let your self-worth depend on stock fluctuations, because the market’s out of your control.” He gives his readers the gift of equanimity and quiet perseverance to carry them through all of life’s ups and downs. Even the epigraph Ben chose for The Intelligent Investor reflects his deep awareness of life’s unpredictability and inevitable hardships:

“Through chances various, through all vicissitudes, we make our way….” Aeneid [Virgil]

Ben inspires his readers to stay balanced and peaceful in the face of peaks and valleys, whether in their personal lives or investment portfolios. I know he means both, because his line evokes Virgil’s hero, Aeneas, who survived the fall of Troy to undertake a perilous journey, enduring harrowing setbacks while leading his people to found a new homeland: Rome.

Ben Summarizes His Value Approach

Ben never mentions “value investing” but does call his investment strategy the “value approach.” Perusing Chapter 12 in my 1949 edition of The Intelligent Investor, I encounter a “Summary” and crucial takeaway, gleaned from Ben Graham’s experience of weathering the Crash and Great Depression.

“The investor’s primary interest lies in acquiring and holding suitable securities at suitable prices. Market movements are important to him in a practical sense, because they alternatively create low price levels at which he would be wise to buy and high price levels at which he certainly should refrain from buying and probably would be wise to sell.” p. 46 (1949 edition) and p. 109 (1973 edition)

Ben Graham stuck with this exact same conclusion in the Fourth Revised Edition, published in 1973. You can see his witty inscription in the copy of the book he gave to me when I was a young woman here. Since he still embraced these sentences twenty-something years after he wrote them, I’m confident they convey his enduring wisdom on how to apply his value approach during periods of market fluctuation.

Later in his “Summary,” Benjamin Graham delivers some practical, no-nonsense advice.

“On the whole it may be better for the investor to do his stock buying whenever he has money to put in stocks, except when the general market level is higher than can be justified by well-established standards of value. If he wants to be shrewd he can look for the ever present bargain opportunities in individual securities.” p. 46

As detailed in Ben’s 1932 Forbes articles, that final sentence reflects precisely what he did in the early 1930s: Driven by a need to recover the heavy losses in his Joint Account, he set out in search of deeply undervalued bargains in a devastated market.

Personal Struggles Amid Financial Ruin

Let’s recap the challenges Ben Graham faced during this time of economic crisis. America was in the grip of the Great Depression, an unprecedented collapse marked by mass unemployment, soup kitchens, breadlines, and homeless encampments.

Unemployed men wait outside a soup kitchen owned by Al Capone in 1930. It was called “Big Al’s Kitchen for the Needy.” Capone fed thousands in Chicago. Bettman Archive.

Ben Graham himself had lost seventy percent of his personal assets, along with those of the investors who depended on him. Due to a novel compensation arrangement, he wouldn’t earn a cent from managing his hedge fund, the Benjamin Graham Joint Account, until he had fully recouped his investors’ losses. The pressure on him to invest wisely was immense.

How difficult it must have been for my grandfather—already struggling in his personal life—to weather those years. In 1927, Ben Graham lost his beloved firstborn son, Newton, to infection. His marriage to Hazel had been strained even before that tragedy, and things didn’t improve after she gave birth to another son, Newton II, in 1928. Now they had four young children, from a newborn to an eight-year-old. While the nation faced economic collapse, Ben was grappling with a more personal collapse—his marriage.

When My Grandmother Took a Solo Cruise

I saw my Grandma Hazel often and knew her well, but not as Ben’s wife or as a grieving mother in the 1930s. I wasn’t born until two decades later. In an earlier post, I touched on some of the issues in their marriage. But what was really happening between them when Ben was grappling with Depression-era financial woes?

I turn now to a treasured letter Hazel wrote to Ben when she was traveling solo. One of them must have saved it, and then their eldest daughter, my mother Marjorie, held onto it through decades and many moves. Before her death in 2011, she passed it on to me. How rare for a granddaughter to gain an intimate glimpse into the heart and mind of a grandmother, especially one struggling in her marriage nearly a century ago.

On Roma stationary, Hazel writes to Ben: “I hate to return-I hate to think of getting off this boat. It is more friendly than my home. A more natural place for me somehow.” Such a sad reflection on the state of her marriage to my grandfather Benjamin Graham.

Hazel didn’t date the letter, but I deduce that she wrote it in May 1930 while aboard a luxury ocean liner called Roma—or so her stationery suggests. My research shows that the SS Roma sailed transatlantic routes between New York, Genoa, and Naples.

SS Roma of the Navigazione Generale Italiana Line, docked in the Port of Genoa, Italy, 1920s.

Since Hazel mentions Egypt, it’s possible the Roma also operated as a cruise ship in the Mediterranean, like many Italian ocean liners of the time, with a port of call in Alexandria or Port Said. Toward her letter’s end, she tells Ben: “Then there was a Sheik in Cairo who begged me to stay.”

Ben did not accompany her on this voyage, nor did her four children, whom she must have left in Manhattan under the care of their governess, Fraulein. In that era, fathers, often working long hours, were largely absent from child-rearing. My mother, age ten, would have been attending elementary school, while the second-eldest, Elaine, age five, would likely have been attending kindergarten.

A Disarmingly Frank Passage

Buried in the heart of her ten-page letter, Hazel reveals how lonely she felt in her marriage. Her words speak volumes about Ben’s emotional distance, suggesting that she feels more capable of communicating with him from a ship thousands of miles away than face to face.

“I have some real ideas & as you’re rather hard to talk with, I’d rather write you if I must talk at you. First let me congratulate you on such a lovely son and say that I hope he’ll live to grow up and give you great joy and happiness. I feel he will.”

Unlike his brother, this son survived childhood and grew into adulthood, but his life was troubled. My grandparents named him Newton, in memory of the beloved son they had lost to an ear infection that led to meningitis—a name, and perhaps a burden, too heavy to bear.

I remind myself that it was a different time, when it was acceptable for mothers to leave their children in the care of a governess for extended periods. Still, I can’t help but sense a lack of maternal attachment in her decision to travel extensively rather than stay near her “lovely son.” When I witness how deeply my own grandchildren miss their mother when she’s absent for work, a day at a time, my heart aches for Hazel’s children, two-year-old Newton most of all.

“The ideas concern you and subsequently me & the children. If I’m to remain your wife, I must help you in some way to justify my remaining your wife. (I assure you that is from my own point of view entirely.) How can I do that? Not physically nor mentally—only by sacrifice. Since it is the only way, I accept it or rather, I’ll try to accept it.”

What kind of sacrifice is she talking about? Divorce was stigmatized in the 1930s and legally difficult. By sacrifice, does she mean staying together for the sake of appearances and the children, when she and Ben were both unhappy in the marriage?

Tenderness, Revealed

“I’ll try to keep up appearances and not to make a fuss, but you must try in every way possible to regain your health. And I have a few suggestions on that score. In the first place I think one month solid this summer would be good. Secondly, just as soon as you can after that another month with no communications with brokerage affairs etc. A three month vacation next summer 1931. And so on as needed & if you still have any money in 1935 a year of complete rest.”

To my surprise, she’s genuinely worried about Ben’s health. For the first time, I sense how deeply she loves him. It’s moving to realize that despite their marital woes and her profound loneliness—so deep she took an extended trip alone—she doesn’t try to change him or tell him how to be a better husband. Instead, she’s concerned for his well-being. In 1930, at thirty-six, he was a man in his prime.

Searching Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street, I find no reference to illness during those stressful post-Crash years. What I do find is a stark summary of 1930—an entry that makes clear why Ben must have appeared so strained:

“Joint Account’s worse financial year, down 50 percent. Receives no income from the Joint Account for [the next] five years. Lives by teaching, writing, and consulting. Marriage to Hazel is becoming shaky.”

He wrote the Memoirs in his sixties and seventies, when age may have helped him forget—or overlook—the health concerns that once worried Hazel.

Hazel’s Leonine Salutation

In his Memoirs, Ben’s chief complaint about their relationship was that Hazel insisted on being in charge: She told him what to do and brooked no resistance. His description aligns with my own memories of her: issuing orders to husband #2 (my Grandpa Arthur) and husband #3 (my Grandpa Lou) during the years I knew her well. She commanded not only them, but also me, my family, and anyone within earshot. Ben expresses this diplomatically in a quote from the Memoirs, which I reprise from my blog post “Benjamin Graham: In Big Trouble with Money and Love”:

“[Hazel] was sure she could handle anything better than anyone else; she naturally took the lead in all practical arrangements; this led her in turn into the habit of bossing those around her, including her husband. I was not the man to tolerate that treatment. Though I liked to oblige and hated to quarrel about anything, I was strongly independent and inwardly resented all forms of domination.”

His resentment of Hazel’s “bossing” makes her salutation atop the letter to Ben, pictured below, especially evocative.

Ben’s wife Hazel greeted her husband with “Dear Pussy Cat” in her 1930 letter, written on letterhead bearing her former address at the Beresford, an elegant apartment they could no longer afford.

“Pussy Cat” may have been nothing more than a private term of endearment Hazel used for Ben, but I can’t ignore its layered connotations: not just someone gentle and affectionate, but also someone meek, compliant, and easily dominated. Note that she writes on stationary from their Beresford address; either they hadn’t yet moved out or she was being thrifty.

In the letter, Hazel does tell Ben what to do—take time off, get some rest—but she sounds more caring than commanding. Her “ideas” read less like orders and more like a wife’s heartfelt pleas for her husband to take better care of himself. In closing her letter, she allows herself to express a complex mix of feelings toward both Ben and herself.

“…but dearest, we start August 23rd, Yes? …Until then, I’m still Your old, bad, loving, imperious, selfish, heartfelt Nuisance, Hazel.”

We know Ben disregarded her orders or pleas—that he didn’t follow her advice. Instead, he worked relentlessly through the end of 1935, not to restore his own health, but to restore the health of the Joint Account.

Comfort for Times of Financial Insecurity

In 1930, Hazel wrote, “if you still have any money in 1935, a year of complete rest.”

She was married to Benjamin Graham, the man myriads still look to for timeless investment wisdom, yet she didn’t know whether he’d have any money in five years.

We can take solace in her words. Ninety percent of us experience money trouble at some juncture in our lives. If Ben’s wife felt it and Ben himself admitted to feeling defeat and near-despair, then financial insecurity doesn’t mean we’re financially incompetent. It means we’re human. We live in a world fraught with social and economic uncertainty. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fluctuates. We can let go of self-judgment and reproach.

Dow Jones Industrial Average 1897-1947, courtesy of The Keystone Co. and The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham, 1949.

Each time our finances hit a low point, we have the chance to pick ourselves up and rebuild—just like Ben Graham, who, I can tell you, was no pussycat. It took him years to find his footing, both financially and emotionally, and to finally build a secure relationship with a woman. But when I knew him well in his seventies and eighties, he was a man who charted his own course and stood firm in who he was.