Everyone who writes about Benjamin Graham tells the legendary story of how he took on Northern Pipeline—a subsidiary of Standard Oil—and triumphed, like David against Goliath. Ben was the underdog: young, slight, and alone. In stark contrast, Northern Pipeline held all the power, commanding the resources and authority he lacked. Ben discovered that Northern Pipeline was sitting on a fortune in railroad bonds, and he ultimately forced them to distribute $110 per share in stock and cash to their shareholders.

Ben Graham’s “disciple” Irving Kahn tells the story—as do Jason Zweig, Warren Buffett, and Ben himself. But none of them pause to ask the crucial question: How did Ben learn to stand up for himself—and come out on top? Where did the accommodating, amiable Ben find the audacity to challenge the big guys and win?

Cartoonist Frank Beard published this cartoon in Judge magazine in 1884, depicting Standard Oil as a monstrous octopus.

Standard Oil was viewed as “the Monster Monopoly” as far back as 1884, ten years before Ben was born. The company controlled 90% of America’s oil refining, struck secret deals with railroads to get cheaper shipping rates, and aggressively bankrupted rivals.

This cartoon, which published in 1904 in Puck Magazine, attacks Standard Oil as an unlawful monopoly out to destroy Congress and the While House. The Supreme Court agreed, ruling in 1911 to break up the Standard Oil monopoly.

Two decades later, the Standard Oil octopus is depicted as even more menacing. In addition to its ruthless pricing strategies that drove rivals out of business, the company was accused of leveraging its immense wealth to manipulate lawmakers and evade regulation. Critics cautioned that it wielded an alarming degree of control over both the economy and the political system. In 1911, the Supreme Court ruled in a landmark case that Standard Oil had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act. Ben sums up the dismantling of Standard Oil in his autobiography, Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street:

“When the Standard Oil monopoly was broken up in 1911 by order of the U.S. Supreme Court, eight of the thirty-one companies emerging from the giant combine were rather small operators of pipelines, carrying crude oil from various fields to refineries.”

In 1926, a mild-mannered statistician named Ben Graham, whose job entailed poring over financial statements at N.H.&L., the brokerage firm that hired him straight out of college, noticed that the pipeline companies owned a large number of unspecified investments. He took the train to Washington, made his way to the Interstate Commerce Commission, and requested annual reports for all eight pipeline companies.

“I soon found I had treasure in my hands. To my amazement I discovered that all of the companies owned huge amounts of the finest railroad bonds.”

The cover of the Standard Oil Bulletin shows pipeline workers in this January, 1918 issue published in San Francisco, California. Photo by Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images.

Ben set his sights on Northern Pipeline—the company with “the largest amount of bond investment in relation to its market price.” Wasting no time, he purchased 2,000 shares out of a total 40,000, making himself the second-largest shareholder after the Rockefeller Foundation. He made an appointment to see the company president, D.S. Bushnell, at the Standard Oil headquarters on Broadway.

The Standard Oil Building, constructed in 1921-28 atop an original building on 1884-85, at 26 Broadway in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan. Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress

“Ben pointed out how unnecessary it was for Northern Pipeline to carry $3,600,000 in bond investments when its gross revenues were only $300,000. These surplus cash resources of $90 per share should be distributed to the shareholders.” Irving Kahn

Mr. Bushnell and his brother, the company’s general counsel, bombarded Ben with one argument after another. The millions of surplus was their “depreciation reserve.” They might need to replace the pipelines, which Ben knew last “practically forever.” Their final excuse for holding onto their pile of gold was the potential need to extend their pipeline. In his Memoirs, Ben recounts his rejoinder:

“But Mr. Bushnell, you have only a little trunk-line segment, running from the Indiana border across the corner of Pennsylvania to the New York border. You are a small part of the old Standard Oil main line. How could you possibly extend your plant in any logical way?”

The Bushnells couldn’t answer Ben’s question. They fell back on a claim of superiority: We know our business—and you don’t. If you don’t approve of how we run the company, sell your shares. In The Snowball, Warren Buffett asserts that they even employed “some anti-Semitic innuendos” to belittle Ben. An exasperated Ben told the Bushnell brothers he wanted to come to the next annual meeting to express his views to other stockholders. His request took them by surprise, but they said he’d be welcome.

Oil City, Pennsylvania, circa 1926. Seneca Street, Looking North. Image courtesy of HipPostcard.

In January of 1927, Ben Graham made the trip to Oil City, Pennsylvania, riding “a rickety local train on a bitter cold and snowy day.” Attendees at the annual meeting consisted of five employees and Ben, the sole outside stockholder. The officers proceeded to adopt and approve the annual report for 1926—but no report was ready. They made a motion to adjourn the meeting. Ben rose to his feet and reminded them that he had a memorandum to read aloud about “the company’s financial position,” i.e. Ben’s contention that they should distribute a chunk of cash to shareholders. They required Ben to submit his request as a formal motion. Too late, he realized his error in coming alone. No one seconded the motion—not even when he argued that they owed him the basic courtesy of a second.

“In a moment, the meeting was over. With ill-concealed snickers, the Bushnells’ minions filed out. I felt humiliated at being made a fool of, ashamed of my own incompetence, angry at the treatment given me. I was able to control my feelings just enough that I was able to say quietly to the president that I felt he had made a great mistake in not letting me have my say.”

Ben’s single, unwavering voice refused to be silenced. He spent the year preparing for the next annual meeting. Through security analysis, Benjamin Graham recognized that Northern Pipeline was an undervalued stock—one with “large realizable assets held at small profit and withheld from the stockholders.”

Ben Graham, the Reformer

“It was my policy first to acquire a substantial interest in such companies and then to endeavor by one means or another to bring about the appropriate change in the company’s capitalization or operating policies.”

Ben took action not only for himself and his hedge fund investors, but also for all shareholders.

“I have never had any question or qualms about the ethics of my endeavors. What I accomplished benefited not only my own people but all the other shareholders, old and new, who were thereby getting only what they were entitled to as owners of the business.”

Ben acquired more shares and retained an eminent attorney, Alfred Cook, whom he described as “a man of great ability and prominence, but—I must add—of even greater pompousness and vanity.” Cook also served as counsel for The New York Times for over half a century, and the paper hailed him as “a leader in the long fight for an independent and competent judiciary,” free from political influence. Reformers in their respective spheres, Graham and Cook proved a formidable pair.

So Close to Oil Money, Ben Could Smell It

One day, Ben met Alfred Cook at the Recess Club, a luncheon club located in a skyscraper, to prepare for the annual meeting. They planned to obtain proxies from all the major shareholders, with the goal of electing one or two new directors to Northern Pipeline’s Board. The biggest shareholder—the Rockefeller Foundation, which owned 23 percent of the shares—had already declined.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr.. Rockefeller Foundation Chairman, at the Senate Oil Investigating Committee in Washington, February 11, 1928. Harris & Ewing, photographer. Library of Congress.

While Ben and Alfred talked over lunch, Ben noticed that the Foundation’s chairman, John D. Rockefeller Jr., was dining at the next table. Ben’s newfound dauntlessness didn’t go so far as to impel him (or his legal eagle) to interrupt Rockefeller’s meal and pitch his plan to reform Northern Pipeline.

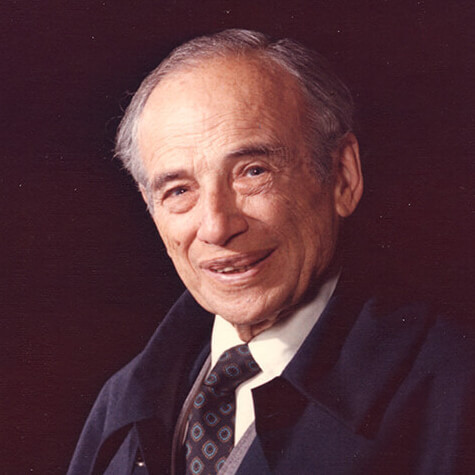

William Schnader, Ben’s Philadelphia lawyer, as seen with his wife in a press photo taken in 1931 when he became Attorney General of Pennsylvania.

Mighty Proud

In January 1928, Ben traveled back to Oil City, Pennsylvania for the annual meeting, accompanied by Alfred Cook and “Henry” William Schnader, the future attorney general of Pennsylvania. Ben had managed to obtain 15,000 proxies from other shareholders, which by law gave his group the right to choose two new directors. Cook nominated Henry Schnader and Benjamin Graham as the new directors. Bushnell tried to get Cook “or almost anybody substituted for [Ben], for whom he evidently didn’t care much.” Cook stood firm. Schnader and Graham were duly elected.

This view of the Standard Oil Company Refining Plant near East Chicago-Indiana Harbor powerfully conveys the immense scale and dominance of Standard Oil. Postcard image courtesy of Postal Treasures.

“I was now the first person not directly affiliated with the Standard Oil system to be elected director of one of its affiliates. Even though Northern Pipeline was tiny compared to most of the others, I was mighty proud of my exploit.”

Bushnell offered Ben a lowball distribution of just $50 in cash per share, but Ben refused to settle. In record time, he spearheaded the effort to distribute Northern Pipeline’s capital surplus and excess railroad bonds to shareholders, ultimately securing a payout of $110 per share—the equivalent of $2,122 today. Why did Bushnell give in without a fight? According to his Memoirs, Ben learned that the majority shareholder, the Rockefeller Foundation, urged management to distribute “as much capital as the business could spare.” He figured they wanted the distributions to add to their pot designated for philanthropic causes, such as the eradication of yellow fever.

“This explanation was most likely true because virtually all the pipelines later followed Northern’s example and made corresponding distributions to their shareholders.”

Ben, who needed to earn a living, took some satisfaction in making a hefty profit for himself and his clients.

Ben Graham, the Original Activist Shareholder

In 2003, the CFA (Chartered Financial Analyst) Institute invited Jason Zweig, then the investing columnist for Money Magazine, to give a talk on the “Lessons and Ideas from Benjamin Graham.” In this talk, Jason Zweig, now the personal investment columnist for The Wall Street Journal and commentator of the 75th Anniversary edition of The Intelligent Investor, noted that Ben Graham pioneered the role of activist shareholder—one who brings about change within companies whose shares they own.

“Graham was the original activist shareholder, long before people like Michael Price or Boone Pickens ever came along. Graham was shaking up companies throughout the 1920s and 1930s. He did it again and again. In the Northern Pipeline case, he even took on the Rockefeller family and prevailed.” Jason Zweig

Zweig compares Ben to two activist shareholders who were familiar to the business community in 2003. Pickens was known as a “takeover operator and corporate raider” in the 1980s. Price, “known for shaking up complacent companies,” was active in 1995-96 with Dial Corporation and Chase Manhattan Bank.

The Lost Ben Graham

In his speech, Jason Zweig reveals that, while writing commentary for the 2003 edition of The Intelligent Investor, he received “a suggestion from a certain resident of Omaha” to take a close look at the 1949 edition. There he found the “lost Ben Graham,” by which Zweig means “a discussion of what Graham called ‘the investor as stockholder.’” Zweig quotes Graham himself, from the 1949 edition of The Intelligent Investor, the same edition that the Omaha resident read at age nineteen:

“Nothing in finance is more fatuous and harmful, in our opinion, than the firmly established attitude of common stock investors and their Wall Street advisers regarding questions of corporate management. That attitude is summed up in the phrase: ‘If you don’t like the management, sell the stock.’”

An idealistic young fund manager, Ben Graham nurtured hopes that shareholders would pay close attention to how managers ran their companies. Zweig goes on to quote a passage from Chapter 19 in the 1949 edition, where Ben urges owners to ask two basic questions:

“1) Is the management reasonably efficient?”

“2) Are the interests of the average outside shareholder receiving proper recognition?”

What if the answers are no? Ben’s response summarizes his victory with Northern Pipeline—including the crucial step of securing shareholder proxies in support of the policy change he championed:

“A few of the more substantial stockholders should become convinced that a change is needed and should be willing to work toward that. Second, the rank and file of the stockholders should be open-minded enough to read the proxy material and to weigh the arguments on both sides.”

Although Ben saw little progress in this direction, he never gave up hope. Benjamin Graham founded the New York Society of Security Analysts in 1937. In his remarks at their 25th anniversary gathering in 1962, he challenged analysts to tackle that very issue:

“My second crusade has been to urge that the Analyst use their judgment and their influence in the area of managerial efficiency—not only towards avoiding the shares of poorly-managed companies (which in Wall Street is often carried too far), but more positively in the support of efforts from stockholders outside the management to improve unsatisfactory results.”

Ben’s talk was published as an article in the Financial Analysts Journal in 1963.

I offer my warm congratulations to the CFA Institute’s Research & Policy Center as they celebrate eighty years of the Financial Analysts Journal! I’m honored that they published a link to Ben Graham’s 1963 article on their 80th anniversary website, as well as a link to an article by Benjamin Graham from their very first issue, published in January 1945.

Financial Analyst: Launching a Profession

I’m proud to share that my grandfather laid the groundwork for the profession of financial analyst. As I mentioned, he was a founder of the New York Society of Security Analysts. In 1947, analyst societies from Boston, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia came together to form a national organization—what is now known as the CFA Institute. In their page about the institute’s history, they credit Benjamin Graham for playing a seminal role:

“Investment analysis became a credentialed profession in 1963, when 284 candidates sat the inaugural CFA® Program exam. From an idea first conceived by famed investor Benjamin Graham, six decades of the CFA Program reflect the evolving dynamics of a complex investment industry.”

What idea of Ben’s do they mean? Essentially, security analysis. Ben Graham scrutinized companies’ financial statements and innovated ways to analyze them that would give investors sound criteria for assessing their investment potential. Jason Zweig edited the book Benjamin Graham: Building a Profession, which traces Ben Graham’s steps toward founding the profession of security analyst. Today, the CFA Institute upholds rigorous professional and ethical standards for financial analysts. It’s truly impressive that more than 200,000 professionals around the world have passed the CFA Exam and earned the prestigious title of Chartered Financial Analyst.

Becoming Ben: From Compliance to Defiance

It’s no surprise that Ben’s mathematical brilliance led him to develop security analysis and create the role of the financial analyst. What’s truly surprising, even awe-inspiring, is that he had the courage to challenge the managers of Northern Pipeline—and prevailed.

Why am I surprised? Because until that moment, he had shown none of the traits you’d expect from someone who challenges power. He wasn’t confrontational—he was acquiescent, inclined to comply and never resist.

What Made Ben Graham So Accommodating?

In my article “Benjamin Graham’s First Worst Memory,” I delve into Ben’s revelation that his mother declared that she had felt the urge to throw him out the window at birth because she wanted a daughter and not a son. To be told that your mother had the impulse to kill you at birth is deeply upsetting and profoundly sad.

Avoiding Criticism and Conflict

How did Ben respond to this hurt, which his mother spoke out loud when he was five years old? He reveals in the Epilogue of his autobiography, Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street, that he possessed an “inordinate sensitivity to criticism.” Writing about himself in the third person, reflecting at age sixty-three on his younger self, he identifies two traits that arose from his oversensitivity:

“The first was his urge to escape any sort of censure by showing exemplary and pleasant conduct. The other was a basic reluctance to criticize others, and this was quickly transformed into an unwillingness to sit judgment upon them… He must be invariably courteous, agreeable, patient; he must avoid conflicts of all kinds, even those of abstract opinions if emotions might be involved.”

Dutiful Son

Ben’s mother’s threat—to throw him out the window—left him perennially afraid to displease her, as if he feared that terrible rejection she threatened. This exceptionally intelligent, spirited, and sensitive boy never allowed himself to contradict, show impatience, or be impolite. Do I know any children who never utter a rude word? I don’t. Clearly, he didn’t believe he was worthy of having his feelings or opinions respected. He grew up as the quintessential good son—excelling in school, juggling multiple jobs to help support his family, and dutifully completing every household chore his mother assigned, including the grocery shopping. He never complained, acted out, slacked off, or questioned her authority.

Ben Graham Didn’t Get the Fair Deal He Deserved

Below, I substitute the word “kids” for “shareholders” in Ben’s second question about evaluating company managers, quoted above:

“Are the interests of the [kids] receiving proper recognition?”

No, not in Ben’s family of origin. Those who wielded power over Ben when he was a boy—his parents and older brothers—didn’t give the smallest, weakest, least esteemed family member a fair shake. Ben witnessed his father beat and verbally threaten his brothers, who in turn, after their father died, bullied Ben. His mother emotionally abandoned him, admonishing him to bear his hurts in silence. My articles about Ben’s relationships with his family members make plain that he felt unseen, uncared for, and unworthy of love and attention.

Dutiful Employee

Ben Graham not only obeyed his mother and forgave his brothers for their hurtful behavior, but also agreed to his boss’s request to take a leave from Columbia College to supervise both day and night shifts at the U.S. Express shipping company. Accepting this job meant taking a leave of absence from the college he had worked so hard to attend—while living in a hostelry, with barely any time to eat or sleep. Even beyond the reach of his family, he was still the good boy, striving to please.

Does this sound like the same Benjamin Graham who challenged Standard Oil? Not in the least. That Ben Graham stood up to the Bushnells. He endured their antisemitic slurs and, undeterred, spoke truth to power. With unwavering resolve, he persevered until he had amassed enough influence to defeat them and secure a director’s seat.

Ben’s Drive to Build a Kinder World

I circle back to my initial question: How did this people-pleaser become a brave and formidable adversary? I believe his courage sprang from a deep emotional drive to right wrongs—to build a kinder world where underdogs, such as he had been as a boy, were treated with fairness and dignity. Ben’s longing to create safety and justice was one of my grandfather’s most endearing qualities. At heart, he felt compelled to ease the suffering of others. He understood what it meant to feel powerless and diminished—both as the youngest son in his family and as a Jewish immigrant in a New York that openly discriminated against Jews.

Fighting for Shareholders’ Rights

Just as his own family had disregarded his rights and needs, Ben saw Northern Pipeline as a company that ignored the rights and interests of its shareholders. He drew on his deep-rooted longing for justice—and found the zeal to confront them

The Moral Force Behind Ben’s Achievements

Ben possessed a fierce drive to right the wrongs of Wall Street, fraught as it was with speculation and corrupt bucket shops. His noble urge to protect others from the pain he had endured fueled his great creative breakthroughs:

- Two decades after his mother invested her life savings and lost everything, Ben Graham not only invented security analysis and value investing, but also taught and wrote books to share his ideas. He equipped his readers, students, and colleagues with the insight and tools necessary to avoid the financial misfortune his mother had suffered.

- After Ben, and nearly everyone on Wall Street and beyond, incurred dire losses in the Crash and Depression, Ben invented an economic approach to prevent a future depression, which he called the Commodity Reserve Currency Plan. As Ben was completing a book on the subject called Storage and Stability: A Modern Ever-Normal Granary, his hopes soared when Herman Baruch offered to present the plan to President Roosevelt in 1937. Roosevelt, however, declined, not wanting to ask the American people to accept another radical economic measure.

Data and Reasoning Gave Him Power and Courage

Ben discloses another factor that emboldened him to become a fierce adversary.

“You are neither right nor wrong because the crowd disagrees with you. You are right because your data and reasoning are right.”

Ben wrote those words in the original 1949 edition of The Intelligent Investor. Jason Zweig, who updated the book for modern readers, describes them as “a wonderful passage on independent thinking.” Despite being young and inexperienced when he faced down Northern Pipeline, Ben had confidence in the soundness of his data and reasoning.

Warren Buffett Carries Forward Ben Graham’s Legacy

Shareholders in overflow rooms watch on a big screen as Berkshire Hathaway Chairman and CEO Warren Buffett, left, and Vice Chairman Charlie Munger preside over the annual Berkshire Hathaway shareholders meeting May 4, 2019, in Omaha, Nebraska. Photo and caption courtesy of Arizona Daily Star.

I’m grateful that Ben’s most prominent student, Warren Buffett, embodies Ben’s ideal of fair and generous treatment of shareholders. Mr. Buffett wrote in his 1996 “An Owner’s Manual” that “Charlie Munger and I think of our shareholders as owner-partners.” Even more telling, attendance at Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting, dubbed “Woodstock for Capitalists,” has grown from a thousand in 1989 to 40,000 in 2025. In The Warren Buffett Shareholder: Stories from Inside the Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting, editors Lawrence Cunningham and Stephanie Cuba offer a cornucopia of views on “why throngs attend year after year.” In his contribution to the book, Jason Zweig writes:

“Buffett has thought a lot about why so many people come to his meetings. ‘First, they come to have a good time,’ he tells me afterward. ‘Second, they come to learn. And they really feel as if they’re partners in the enterprise.’”

Attendees feel they are partners because Buffett and his fellow directors welcome questions, admit mistakes, and exemplify fairness, openness, and kindness to shareholders. Nearly a century after Northern Pipeline, Buffett follows Ben Graham’s luminous example. Mr. Buffett makes business decisions based on his commitment to do right by shareholders. If my grandfather could see Warren Buffett now—devoting his life to making profits for his shareholders and giving his share to charity—Benjamin Graham would flash his wide, heart-warming smile.