When Benjamin Graham was born in 1894, he became a member of a family which consisted of his parents, Dorothy and Isaac, and his two older brothers, Leon and Victor. In the first chapter of Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street, Ben hints at the difficulties he faced as the youngest of three boys:

“Victor was born fourteen months after Leon, and I appeared thirteen months after Victor. This closeness of our ages proved most disconcerting to me as the youngest. But, from the practical point of view it had numerous advantages, since it facilitated our being brought up as a unit.”

I can’t help but notice Ben Graham’s evasive syntax. “Disconcerting” strikes me as a euphemism for a stronger word, like distressing. “But” shifts the topic from Ben’s emotional life to a distant “practical” realm. Practical from who’s point of view—his mother’s? When Ben was born, Dorothy had three sons age two and under, all of them likely in diapers. Nothing practical about that. Years later, after the Grossbaums settled in New York and became sufficiently well-off to employ a governess, practical advantages emerged.

I’m interested in why the brothers’ closeness in age “proved most disconcerting” to Ben. Disconcerting how? How did his brothers treat him and how did that affect Ben?

Forgetfulness of Injuries

Right away, I find evidence of problems—and hit a road block:

“Fortunately, I am unable to remember any specific example of injustice or mistreatment at [my brothers’] hands. (This forgetfulness of injuries, or of disturbing events generally, became one of my most characteristic traits, sometimes carried to lengths which amazed others and even surprised myself.)”

This quote strikes me as a smoking gun. The length of Ben Graham’s parenthetical qualification—much longer than his initial assertion—implies that there are numerous “injuries” and “disturbing events” that he has forgotten and left out of his Memoirs. He did write about some of his worst memories of his mother and father, but not a single “worst” memory of his brothers. It sounds like he repressed painful memories, in the Freudian sense of excluding them from his consciousness. It sounds, too, like what happened was more serious than normal sibling fights. He repressed the specifics while retaining the certainty that he suffered injustice and mistreatment at his brothers’ hands.

Why would he repress those specifics? As the youngest boy, he looked up to and relied on his brothers. They were his only allies, when navigating their often absent and, at times, violent father, and their emotionally unavailable mother. Ben couldn’t afford to stay mad at Leon and Victor for long. He needed whatever modicum of companionship and protection they could offer. When they hurt him, he forgot the injury so fast, he amazed “others.”

Sharp Words, Unfair Actions

“But I do recall my general feeling of being ill-used. With some bitterness, I once resolved to inform them of their wrongs. For their birthdays I planned to write a list of their sharp words and unfair actions and to present these to them marked ‘FORGIVEN’ as birthday gifts. But I never did so.”

I find this recollection so touching—my grandfather’s longing to have his hurts acknowledged, to grant his brothers the gift of his forgiveness, and to incline them toward becoming less callous and more caring toward him.

Ben never wrote that list. He never confronted them with the times they hurt him. Their male role model—their father—had used threats and blows to control and punish Leon and Victor. I concede that “thrashing” children who misbehaved was customary in the 1900s, before we had studies that show that striking a child increases their risk of developing anxiety and depression, aggression, alcohol and drug abuse, partner violence, and suicide, later in life. But Ben’s father’s belligerent threats, such as to break every bone in his son’s body, was not customary. When Ben was eight, Victor nine, and Leon ten, Isaac died suddenly, leaving those wounding male behaviors stamped indelibly on their psyches. When angry or stressed, the two older boys likely hit and intimidated their younger brother, following their father’s example.

Ben was a safe target, in part because their laissez-faire mother wasn’t likely to intervene.

Still a Baby

On page fourteen of his Memoirs, Ben Graham remembers an early school experience that distressed him:

“At five, my schooling began—ignominiously. I was sent to a public kindergarten nearby, located on the second floor of some building. I remember sitting in ecstasy before a box containing sand and a large shell, with which I played to my heart’s content. But I was soon to be expelled from Arcadia. I had not yet mastered the difficult art of unbuttoning and buttoning my pants, although all the other pupils had passed that critical point in their education. Thus my visits to the toilet required the assistance of a busy teacher.”

I can’t help but smile when I picture my little grandfather in this predicament. One of my children had the same problem in kindergarten, and I’m grateful his teacher was willing to assist him. We helped by shopping for pants with snaps that didn’t require fingers of steel to close.

For Ben, this was no smiling matter.

“After a few days of that nonsense, I was sent home, never to return. Thus I was compelled to wait until September 1900, when I was almost six and a half, before I could begin again, in first grade. I was very impatient to start, my brothers having taken on insufferable airs because they were in school and I was still a baby.”

“Insufferable airs” tells us that his brothers lorded this over Ben, using it to justify their superiority. Ben Graham conceals his own suffering inside the word “insufferable.” I think he really did suffer. To be held back from kindergarten for developmental reasons, by the standards of his time, must have been mortifying. His expulsion from school made him vulnerable to the shameful epithet: “baby.”

At age five, Ben seems to have resented his brothers’ “insufferable airs” more than losing out on his kindergarten year. I sense that their arrogant disparagement still galled the septuagenarian penning his Memoirs. The taunt “baby” may have summoned up his humiliation at appearing in the portrait of the three brothers wearing girlish “short skirts.” These shame-filled moments ignited Ben’s drive to compete with and surpass his older brothers—a subject I’ll return to in this and future posts.

Problem Child

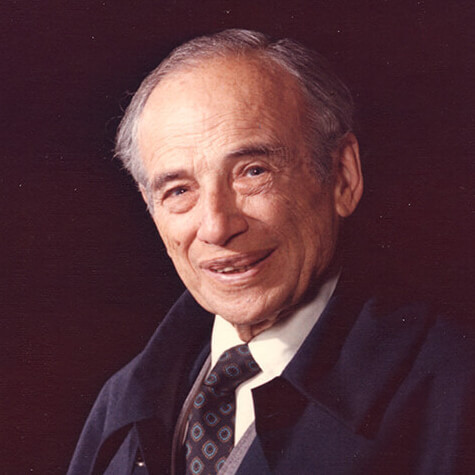

I knew Ben Graham’s brother Victor as my gracious great-uncle, the one with his arm around Ben who smiles from ear to ear into my mother’s camera atop this post. So I’m startled to discover, on page eight of the Memoirs, this unfavorable report about Ben’s middle brother Victor as a boy:

“Victor was by then proving something of a problem child and it was thought best to send him to Dr. Davidson’s well-known summer camp at Coolbaugh, Pennsylvania, for increased discipline.”

Ben Graham’s syntax distances him both from the negative evaluation of Victor and the decision to send Victor to Dr. Davidson’s. “By then” refers to the summer of 1901, when Ben was seven, Victor eight, and their older brother Leon nine. Victor had apparently behaved so badly that their parents, Dorothy and Isaac Grossbaum, decided to leave Victor behind that summer when the family traveled to England to visit their British relatives. Victor missed this once-in-a-lifetime chance to sail the Atlantic, meet his grandparents, and visit London.

His parents’ decision to relegate him to a disciplinary setting, whose purpose was to shape up difficult boys, must have felt harsh. Victor was only eight years old, awfully young to be separated from his family for a long stretch—separated by an ocean that made visits impossible. I ache with sympathy for him.

I’m curious about what kind of misbehavior warranted leaving Victor behind. Poor impulse control, insolence, tantrums? Did Victor become enraged when he thought his father’s beatings were undeserved, and hit back? Was Victor so out of control, that he would have disrupted the visits with their British relatives?

Undisclosed Misdeeds

Ben tells us nothing, relating not a single instance when Victor got into trouble. In the mid-to-late 1960s when Ben began writing his Memoirs, his parents, Dorothy and Isaac, were deceased. Ben’s oldest brother Leon had died of a heart attack in 1962, at the age of seventy-one. Victor was the one family member Ben had left. Understandably, Ben avoided disclosing any bad behavior that might embarrass Victor and jeopardize their relationship.

Victor the Delinquent?

Rather than become less rebellious after the boys’ father died, Victor’s behavior got worse:

“Victor was the enfant terrible of the family. During his teens, he developed into a real problem child—the sort referred to as a ‘delinquent’—but he came out of a period of institutional discipline much changed for the better.”

“Enfant terrible” is a term for a person who makes shocking remarks and engages in outrageous behavior. A “delinquent” often commits minor crimes. Did Victor do those things? Ben doesn’t say. Did the “institutional discipline” consist of summers at Dr. Davidson’s camp? Or did their parents send Victor to a reform school? Another subject Ben doesn’t discuss.

Ben’s evasiveness in this quotation is so extreme, it speaks louder than the sentences he wrote. Ben Graham wanted to skirt around the “delinquent” phase of Victor’s life and leapfrog to the phase when Victor “changed for the better.” Ben displays admirable, sometimes self-effacing honesty in the Memoirs, like when he details his awkwardness as a boy later in this post. Ben Graham’s native honesty didn’t allow him to pretend that Victor’s unruly phase never happened.

The Good Son

“I was very well-behaved, rarely getting into any kind of scrape unless led astray by my brothers.”

Ben Graham saw how his older brothers fared when they got into trouble. He decided to be the least troublesome son—the son who obeyed his mother, did chores, suppressed his needs and feelings (as she silently demanded), and shined at school. Ben Graham’s zeal to prove to his mother that he was better than his brothers fueled a blazing drive for success.

Torture Contraption

While longing for his mother’s approval, Ben also yearned to be one of the boys. Victor showed Ben (and presumably Leon) how to make a device with a screw, a knotted cord, and a red washer used in beer bottles. Notice how Ben’s memory retrieves these details! The boys licked the washer, attached “the torture contraption” to a florist’s greenhouse window, and ran the knotted cord through their fingers, making a sound “a bit like machine-gun fire. The exasperated proprietor would dash out of the store, shouting invectives and threats, but we always managed to escape.”

Would this infraction be serious enough to earn Victor the moniker “delinquent?” No.

Having avoided recounting any of Victor’s serious transgressions, Ben Graham relished recalling how the boys got up to harmless mischief, causing no damage to person or property.

Mischievous Leon

What about Ben’s relationship with his older brother, Leon? I wish I had memories of my great-uncle Leon, but I don’t. Ben describes him in the Memoirs:

“Leon, the eldest, had the best-balanced personality of us three. He was a normal, mischievous, down-to-earth youngster who was often in hot water—but never at scalding temperatures.”

By deeming Leon “best-balanced,” Ben signals he knows that his being the “very well-behaved” son represents an imbalance—an overcompensation. “Never at scalding temperatures” compares Leon with Victor, intimating that Leon never did anything as terrible as Victor.

American Eel, native to the Hudson River, New York

Ben betrays a stifled boyish glee when recounting one of Leon’s shenanigans, which begins with this irresistible sentence: “An enthusiastic fisherman at nine…one day he caught an eel.” Leon proceeded to cut up the eel and hide a segment under each diner’s napkin at a Sabbath dinner, which included esteemed guests. Isaac, the boys’ father, who had grown up with an Orthodox father, presided.

“The result was minor pandemonium. Everyone knew instinctively that he—or mainly she—was gazing at some weird substance strictly forbidden by the Mosaic code. It was touch-and-go whether the expensive service-plates would have to be thrown away….Leon was duly punished for his dereliction.”

Ben uses passive voice to avoid identifying the punisher—no doubt their father Isaac. The Mosaic Code is the ancient code of laws that, according to the Old Testament, God gave to Moses. I can confirm that Book of Leviticus prohibits eating any living thing that has fins, but no scales. Jewish law considered eels to be unclean, and even an abomination.

A Special Fondness

On page thirty-eight of the Memoirs, I encounter Ben’s tale of coming home chilled to the marrow after his blistering cold solo ice-skating foray in Central Park—solo why? Because his brothers excluded him from their plans? How often did that happen? Ben doesn’t say. He does reveal that “we were supposed to cure our own wounds and complain about nothing.” This code of silence helps explain Ben’s taciturnity—his eschewal of lodging any complaint about his brothers’ maltreatment of him.

He goes on to say that contending with his brothers made him stronger:

“Obviously, my relations with my brothers were also bound to toughen me. They were in no sense bullies; indeed, they had a special fondness for me which was destined to endure sixty years and more.”

Ben says his brothers “had a special fondness for me.” It’s telling that he doesn’t say he had a special fondness for them. I posit that his sense of being treated unjustly by them, when he tried so hard to be a good, uncomplaining brother, impeded affection. To get along with them, he learned to control his emotions—to quash his anger with them, his disappointment, his outrage—also quashing his capacity to feel love.

“But they were older, bigger, stronger, and much more practical. As early teenagers, they could scarcely be expected to show much unselfishness or delicacy of feeling towards me.”

Ben recognizes that teenagers can be tough on a younger sibling. Still, if you turn Ben’s assertion around, it says: “My brothers behaved selfishly and without delicacy of feeling toward me.” “Practical” may be a quality Ben associated with mature masculinity, which he lacked. His brothers must have teased him for being small for his age, “incurably absent-minded,” and physically awkward. Ben Graham confesses that he “would drop things, break them, or run into things and damage them and sometimes myself.” Might that be what he thought of as impractical? Reverberating down two generations, the “sharp words” they likely flung at him—“baby, weakling, shrimp, butterfingers, sissy, klutz”—pierce my elseways vulnerable heart.

How Bad Was It?

How often did Ben’s brothers make him cry? Knock him down, accidentally on purpose? Beat him up? Children who were hit often become hitters. They do to others what was done to them. Given that the older boys had been subjected to their father’s bullying, it likely was bad. Ben Graham won’t recall and won’t tell.

He does say:

“[T]hose who loved him dearly would so often wound him, with nonchalance or even with malice.”

“Those who loved him dearly” means his parents and brothers. Ben’s mother depended on her older brother Maurice, who generously gave her money to live on and intermittently housed her family under his roof, but Ben never regarded his “ill-tempered and tyrannical” uncle, his “sweet…ineffectual” aunt, or cousins as loved ones. Ben Graham is talking about his closest family members; Isaac, Dorothy, Leon and Victor.

We know that his mother Dorothy wounded him with nonchalance—nonchalance in the sense that she seemed casually unconcerned, not going to the trouble of giving attention or comfort, disinterested in her sons’ injuries and safety. We know that Ben’s father didn’t hurt Ben directly, but rather by forcing Ben to witness him abusing his brothers. That leaves his brothers, probably reprising their father’s threats and blows, who hurt Ben “with malice.”

Ben wrote in his “Self-Portrait at Sixty-Three,” published in the Memoirs, that “very early in life he set to work, like a beaver, to build a breastwork around his heart.” “Breastwork” means a defensive wall. At age sixty-three, he saw that he had built that wall to protect himself from the wounding inflicted by “those who loved him dearly”—his parents and siblings.

In a flash, I see that forgetfulness was Ben’s “breastwork”. What better way to defend against painful events than by deliberately or subconsciously forgetting them? If you block them out, you don’t suffer hurt.

Or not as much.

Sibling Rivalry or Bullying?

Sibling rivalry—jealousy and competition between siblings—flares up in every family I’ve known. Competition tends to be fiercer among siblings who are close in age, like Ben and his brothers. Fiercer in families with an inaccessible mother like Dorothy, where the children vie for the scant maternal attention and affection they hunger for but rarely receive.

Ben Graham intimates that what he suffered goes beyond sibling rivalry to something closer to bullying. Ben doth protest too much, methinks, when he denies that his brothers were bullies. If I read between the lines of the smoking gun and other quotes from his Memoirs—between the euphemisms, evasions, passive voice, and outright omissions—I feel sure that his older brothers ganged up on Ben, humiliated him for being small and weak and clumsy, excluded him, and hurt him, physically and emotionally. I’m sure that his father and mother wounded him, too.

Why am I sure?

Because his brothers’ humiliations set Ben ablaze with ambition to prove to himself, Dorothy, Leon, and Victor, that the “baby” could be as big a man as his brothers. In his teens and twenties, he could work more jobs to help their mother, excel at academics, land a Wall Street job, and surpass them as the main family breadwinner. He even competed with them for a girl. Did he win her? You’ll find out in a future blog post.

And, because Ben got damaged. He shut down emotionally, erecting a wall of forgetfulness and denial. He grew up to be a man closed off to feelings. Generous and affable, he made no close male friends. He failed at three marriages. “Ben Graham always had a shell around him”, Warren Buffett told me. We’re talking about lasting damage that Ben Graham didn’t recognize until he was sixty-three.

It took my grandfather a lifetime to heal. I’m awash in admiration that he did heal, as much as he could. I undertook this journey of tracing his evolution as a person, because I’m grateful and awed that after suffering childhood traumas, he became the friendly, contented Grandpa Ben I knew and loved. His story offers us a special kind of hope.