Long before protests erupted on the Columbia College campus, pictured above in 1910, the teenaged Benjamin Graham attended Columbia on scholarship and took his first investment risk. Most college students don’t think about investing—they have no cash to spare. That was the case for my grandfather until a chance to make big money fell into his lap. He was taking a heavy load of classes, determined to complete his undergraduate degree in three years. He also worked “a great variety of jobs” to cover his “personal and college expenses.” He recalls those jobs in fascinating detail in his autobiography, Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street. The story of the most exhilarating and lucrative job of them all—so lucrative that Ben saved enough to invest!—begins with the job that came before.

“In my freshman year I worked as cashier in a movie theater in Park Row, near the Bowery and Chinatown from 5 p.m. to 10:30 every weekday, plus a twelve-hour stretch on alternate Sundays. My pay was $6 per week, of which sixty cents went to carfare.”

The commute from Columbia College, located in Upper Manhattan, to the Bowery and Chinatown in Lower Manhattan, likely took Ben an hour by bus or trolley. I presume that’s what he means by “carfare.” He averaged thirty-three and a half hours at the movie theater per week and earned eighteen cents per hour. His wages must have barely covered his expenses. His college scholarship paid for tuition—not books, not room and board. Ben (seventeen) lived at home, sharing an apartment with his mother, Dorothy, and two older brothers, Victor (eighteen) and Leon (nineteen). His brothers had finished high school and joined the workforce, unable to afford college. Their low-paying jobs barely supported them and their mother. Ben strove to do his part and yearned to outearn his brothers.

Opportunity Knocked

“At the end of my first college year, in early June, a friend passed the theater and stopped to chat. He had just started a wonderful job, paying $40 per month for regular day hours, and $50 per month on the night shift. They needed more college men, and he thought he could swing it for me. Of course I was interested. After a brief interview, I signed up for the night shift, running from 4 p.m. to midnight, six days a week. My employer was the U.S. Express Company; my boss was M.A. Fisher, an efficiency expert.”

Now he worked forty-eight hours per week and earned twenty-four cents per hour, a 33.33 percent pay raise. He attended classes and studied by day, then worked every afternoon and night. It’s not surprising that he tells us: “I made no close friends at Columbia.”

Teenaged Benjamin Graham Meets Baby IBM

Ben Graham’s job with U.S. Express offered far more excitement than selling movie tickets. At U.S. Express, Ben joined a project designed to calculate how much new rates for express shipping, set by the Interstate Commerce Commission, would impact revenues. Other express companies, like Wells Fargo, tallied their daily shipping at the old and new rates by hand. Mr. Fisher, Ben’s boss, led U.S. Express to use “a punched-card or Hollerith method for rapidly sorting and tabulating complicated data.”

Hollerith Electric Tabulator, US Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 1908.

Photograph by Waldon Fawcett. Library of Congress, courtesy of officemuseum.com.

“Hollerith machines were leased by a weakly financed and poorly regarded company called Computing-Tabulating-Recording Corporation. Its stock was said to represent nothing but water, and may have been worth, say, $3 million in the market. Little did I suspect that someday I would see the stock of that company, renamed International Business Machines, sell on the New York Stock Exchange for billions of dollars.”

Ben and the rest of the crew of college men punched cards with the old and new shipping rates. They ran the cards through the Hollerith tabulating machines, which produced various totals, including rates for interstate versus intrastate shipments. Ben Graham and his classmate, Lou Bernstein—the boy who introduced Ben to his first love, Alda—became so interested in the work that their boss, Mr. Fisher, invited them “to his home one Sunday afternoon for a long bull session.” The young men’s growing expertise would have “unexpected results.”

Ben Graham’s Brilliance Shines Through

In September of 1912, Ben had begun his sophomore year at Columbia. He was eighteen years old. He attended classes during the day, “carrying about twenty-one hours per week of classes plus homework.” Then he commuted to U.S. Express, where he and Lou Bernstein worked from 4 p.m. until midnight. One evening, they learned that Mr. Fisher had “resigned after an altercation with the general auditor, Mr. Tait.” That same night, Mr. Tait asked to see “Bernstein and Grossbaum” after work. (Ben would change his name from Grossbaum to Graham in 1914.) Mr. Fisher had kept his finger on the pulse of the project, whereas Mr. Tait had not.

“[Mr. Tait] had been informed, he told us, that we two had a very good understanding of what was being done; was that true? Without undue modesty, we said it was…Did we think we could take Fisher’s place and boss the job? Yes. Could we prepare immediately—and have ready by the next evening—a complete outline of every step in the process? Yes. Would I—Benny Grossbaum—arrange to apply for a leave of absence from college, take over the day shift, and assume primary responsibility for the job?”

Thoughts assail me faster than I can write. First, my grandfather was so smart that his boss saw teenaged Benjamin Graham as capable of taking over from an innovative efficiency expert as manager of a complex operation. Second, Ben didn’t consider saying no. Why not? One minute, he was working his way through college, and the next minute, he was giving up college in order to work. Taking this job meant quitting mid-semester for an unknown time period. He was a people pleaser, sure, but chiefly, he said yes because of money.

The Dean Consents

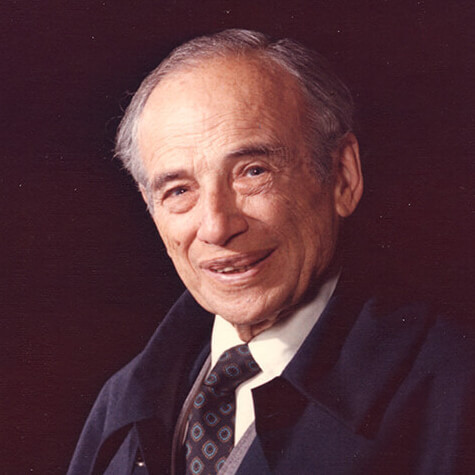

Portrait of Frederick Paul Keppel by Leopold Seyffert, 1929, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute.

The next day, Ben Graham obtained the consent of Frederick Keppel, Dean of Columbia, to take a leave of absence. Dean Keppel, who would later distinguish himself as president of the Carnegie Corporation, saw business experience as educational and offered to give Ben credit if he could pass his semester exams.

Ben and Lou got to work, outlining the steps requested by Mr. Tait on a piece of ruled cardboard. I’m familiar with my grandfather’s handwriting—a sometimes illegible scrawl. See it for yourself on this postcard to Warren Buffet. Luckily, Lou had excellent penmanship.

“At the bottom of the chart, we wrote the following sentence, doubly underlined: ‘ALL STEPS ARE TO BE CHECKED AND DOUBLE-CHECKED FOR ACCURACY.’”

That line, more than the steps that Mr. Tait didn’t fully understand, persuaded Mr. Tait that Ben was ready to assume responsibility for the entire operation. Lou would assist him.

A Mighty Fancy Salary for a Kid

“Then [Mr. Tait] asked me, ‘What salary do you want to take charge of the job?’ I looked him steadily in the eye and said: ‘You’ll have to double my pay, sir.’ ‘Done,’ he said in a flash. I realized that my request for $100 per month had been overly modest—but it was too late to change anything. Bernstein settled for a 50 percent raise, or $75 per month. But he didn’t have to take a leave of absence from college.”

Ben knew that he’d undervalued his worth to the company and asked for too low a salary. Mr. Tait was, in Ben’s words, “overflowing with maudlin gratitude.” He promised to “personally guarantee” that Ben would finish college when he went back. Then Mr. Tait asked—a bit late, in my opinion—how old Ben was.

“I just couldn’t bring myself to confess that I had just turned eighteen. So I lied—rather rare for me, then and since—and said that I was nineteen going on twenty. He shook his head and muttered that I was going to get a mighty fancy salary for a kid

I believe that sweet salary clouded Ben’s view. He’d gone to great effort to win a scholarship to Columbia, thinking the college would open doors to a high-paying career. That mighty fancy salary would dry up soon enough. Perhaps Ben had no fear that he’d lose his place at Columbia. Yet he’d been racing to complete his studies, and now his studies had screeched to a halt. He would lose time, as well as something crucial that we’ll discover when he interviews for his first job.

Ben and Lou supervised the “large staff of employees” for four and a half months. Ben made one key improvement in the operation—“a new arrangement for punching and sorting subblocks for certain shipments which had not been organized in the original card design”—for which he received praise. But he admits that “as managers of a large staff of employees, we undoubtedly lacked maturity and savoir faire.” I smile, imagining my slight, eighteen-year-old grandfather overseeing workers twice his age.

Ben’s Unbelievable Next Step

“Then something crazy happened. In response to Vice-President Platt’s dissatisfaction with our rate of progress, Tait decided that we must run three shifts and I would have to run two of them—not only the one from eight to four but also the graveyard shift from midnight to eight. This would leave me all of eight hours a day for dinner, sleep and recreation. After all, I was young and could take it.”

Ben said yes, without considering how far his quality of life would plummet. Recreation? Maybe in his dreams.

“It was clearly out of the question for me to travel up to the Bronx each day to sleep, so I arranged to spend the night at an old and famous hostelry on Cortland Street known as Smith & McNeill’s.”

Just for fun—a photo of Charlie Chaplin as The Star Boarder and Minta Durfee as the Landlady, in a 1914 silent film called “The Star Boarder.” Not Ben’s boarding house.

A Princely Salary

“After finishing the day shift at 4 p.m., I would eat some kind of meal and crawl into bed around 5:00, leaving word to be awakened at 11:30. Then my workday would start in pitch darkness, running on for sixteen hours, with two forty-minute breaks. The company rules provided for time-and-a-half pay for overtime. My first semi-monthly check came in a the rate of $250 per month—a princely salary for those pre-1914 days.”

For the first time in his life, Ben Graham was earning serious money. Imagine his exhilaration. I’m not surprised that he was willing to sacrifice. He could neither sleep in his own bed nor eat his mother’s cooking. He bought dinner—surely an inexpensive meal—and slept six and a half hours in a rented bed. He must have grabbed breakfast and lunch during those forty-minute breaks; otherwise, he would have gone hungry.

My grandfather hadn’t learned how to say no or set limits when a powerful person asked too much of him. In my humble opinion, a sixteen-hour workday is too much for anyone, especially a teenaged boy. What would you say if your college-aged son called to discuss this sixteen-hours-per-day job offer? You would say, “No, don’t do it!”—unless you were poor and relied on your son for financial support. Ben’s poverty drove his decision. Having labored all summer on a farm for ten dollars a month plus room and board, $250 a month sang an irresistible siren song.

My Grandfather Undervalues Himself

“[My high salary] bothered Tait. He said it would cause dissatisfaction among important employees earning less than I did, and he asked me to accept regular pay [instead of the company-mandated time-and-a-half] for the second shift. I agreed.”

Under pressure from a boss, Ben Graham was willing to underrate his worth and accept lower pay. Fortunately, U.S. Express ended the night shift two weeks later.

“The graveyard shift workers were so inefficient, and probably my own supervision was so imperfect, that much of our labor was offset by mistakes. So the experiment was soon dropped. I went back to my $100 a month and normal way of life. Mother was happy.”

Normal for Benjamin Graham. Not normal for most college kids, who didn’t work nightly, six days a week. While preparing to re-enter Columbia, Ben studied for semester exams in English, French, German, and mathematics. He did neglect one class—the one essential to his future career.

The Budding Economist Drops College Economics

“I had begun elementary economics before leaving college, but the first weeks of exposure to ‘the dismal science’ had failed to arouse my interest, and I decided not to pursue it when I returned. As things turned out, I was to make my lifetime career in that branch of economics called ‘finance’ and to become a professor of the subject in two of our larger universities.”

It tickles me that economics failed to pique my young grandfather’s interest. Benjamin Graham became a self-taught economist who invented a visionary strategy for stabilizing the economy, which he called the Commodity Reserve Currency Plan. The Plan was never adopted but garnered serious consideration “as part of [FDR’s] anti-Depression program.”

“I have learned whatever I know about economics the same way I learned about finance—by reading, meditation, and practical experience.”

The Father-To-Be of Value Investing Loved Literature More than Math

French cabaret singer and actress Yvette Guilbert, who modeled for Toulouse-Lautrec, in 1913. Courtesy of Bain Collection, Library of Congress

Although he was a math major, Benjamin Graham’s college memories gravitated to the humanities. At a meeting of French scholars, he was “deeply moved” to hear Yvette Guilbert—a famous French actress “known by Toulouse-Lautrec and Proust”—perform a poem. He won third prize in a French essay contest. He aced his German literature course “with an unprecedented A+.” His philosophy professor quoted a clever line from Ben’s paper: “What Descartes has put asunder, let no man join together.”

Ben Graham reports with pride that a popular English professor, John Erskine, complimented him on his observation that “no constable or other representative of the law” ever makes an appearance in Wuthering Heights. A second English professor helped him hone his romantic poetry, and a third, Dr. Tassin, became a friend and investor. Ben Graham cites his experience as one of a small group of honor students who met twice monthly for an English-history-philosophy seminar as “the high point of my academic career.” At Columbia, Ben Graham blossomed into a Renaissance man—the polymath who found meaning and delight in culture. On visits during his retirement years, I saw my grandfather take pleasure in devoting himself to translating literary works—classical Latin poetry, a Portuguese novel, Homer’s Iliad—into English.

The Future Intelligent Investor Makes an Unintelligent Investment

Ben Graham resumed his studies at Columbia with a savings of $500 from his stint as a manager at U.S. Express. For a teenager in 1913, this represented a lofty sum—more than he or his family had seen since his mother lost her life savings in a bucket shop scam. I believe my grandfather intended to keep that money as a cash reserve.

In early childhood, Ben and his brothers had watched their father Isaac succeed admirably at starting a New York branch of Grossbaum & Sons—the family china import business in London. Soon after Isaac died of pancreatic cancer, the Manhattan store failed. Ben’s oldest brother, Leon, had taken a job in this familiar line of work.

“Leon had long been anxious to rise above his position as chinaware salesman in Wanamaker’s.”

Ben’s brother no doubt yearned to own his own business, as their father had done.

“Leon was attracted by the possibilities of the fast-growing movie industry. He wanted to buy a small theater in Jamaica, Long Island—then not much more than a village—for $1500. Mother borrowed $1000 from her rich sister in Warsaw, and I turned over all my savings from the U.S. Express job to pay the balance.”

We’re witnessing Benjamin Graham make his first major investment. Having worked as a cashier at two movie theaters in New York, he had some hands-on experience with “the fast-growing movie industry.” Did he consider the prospects for ticket sales in Jamaica, looking at the local population, their income, and spending habits? Did he analyze whether the theater offered good prospects for generating profits? I’m sure he didn’t. He made the decision to invest— everything he had!—based on family loyalty and brotherly competitiveness. The fierce sibling rivalry of his youth heightened his triumph at becoming the family’s top earner and his brother’s benefactor.

Financial Disaster

“As might have been expected from Leon’s youth and total inexperience, the enterprise proved a complete flop, and all the money was lost in a couple of months.”

An inflation calculator reveals that $500 in 1913 was the equivalent of $15,774 in 2024. Ben and his family were penniless again. The loss blindsided them.

“Now I had no funds and no job.”

That work marathon at U.S. Express turned out to be all for naught—and might have cost Ben his career. A year later, just as Ben was graduating from Columbia, Mr. Alfred Newburger, of Newburger, Henderson and Loeb, interviewed Ben for his first job on Wall Street.

“He asked me about my studies in economics, and I had to admit that I had skipped the subject completely—largely because of my job with the U.S. Express Company.”

Fortunately, Ben “knew the difference between a stock and a bond.” Dean Keppel recommended him, and Mr. Newburger hired him. The bad investment Ben Graham made at eighteen—the desolation of failure, the pain of losing everything—galvanized him to minimize risk and maximize gain. Rising from the ashes of this early financial debacle, the future inventor of security analysis set out to find a better, safer, more profitable way to invest.