My readers know I like to toot my grandfather’s horn, so it may surprise you to learn that I’m curious about this skeptical view expressed by the late, great Charlie Munger: “A lot of Ben Graham’s rise in life was during a period when there was plenty of low-hanging fruit among mediocre businesses that were way too cheap. He was relatively rare in doing his hunting in that garden, and so he made a pretty good living.” “Mediocre and cheap”? I find myself spoiling for a fight. Yoohoo, Mr. Munger, my Grandpa Ben made “a pretty good living” because he devised an ingenious new strategy for figuring out how to pick financially rewarding “fruit.”

Charles Munger and Warren Buffett at Chinese electric automaker BYD’s press event in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, China, September 27, 2010. Photo by Nelson Ching/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

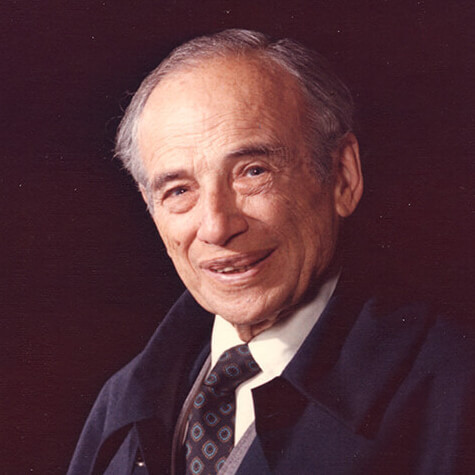

The legendary Mr. Munger spoke the words quoted above in February 2023 at the Daily Journal Corporation Annual Shareholders Meeting in Los Angeles. On reflection, I take it as a compliment. Here, this ninety-nine-year-old investment titan, partner to Warren Buffett, spent precious moments at a major public forum—where eager shareholders hung on his every word—criticizing my grandfather. Yes, speaking about my grandfather as if he were a larger-than-life challenger for Wall Steet domination. Yes, passing judgement on Benjamin Graham—who’d died forty-seven years previously and wasn’t around to defend himself. In point of fact, my grandfather was pretty old-timey and retro, considering he started picking that low-hanging fruit over a hundred years ago.

Low-Hanging Fruit

What did Mr. Munger mean by “low-hanging fruit”? In business contexts, we’re talking about easy ways to make money, like reaching out to bring in old customers or offering a promotion to attract new ones. But that’s not what Mr. Munger had in mind. He’s talking about buying shares of “mediocre businesses” whose stock is selling at “cheap” prices. He’s talking disparagingly about the inferior quality of the businesses Ben chose compared to companies like Coca-Cola and Apple and Bank of America, whose shares Warren Buffett currently owns. Still, buying bargain stocks is one of the central tenets of value investing:

Buy stocks whose intrinsic value far exceeds their price.

I agree with Mr. Munger that Ben Graham was “relatively rare in doing his hunting in that garden.” However, I want to register my gripe about the mixed metaphor. Hunters hunt; they don’t pick fruit in gardens. Secondly, let’s consider why Ben was one of a few—or even the first—harvester in that garden. In his position as statistician at Newburger, Henderson & Loeb, he discovered those trees with the low-hanging fruit. He saw that their imperfect fruit would be tasty. He pored over financial statements and calculated which investment vehicles—bonds or stocks—were selling at prices well below their value. Few others were buying; Ben Graham invented security analysis and utilized his analytical calculations to ferret out stock market bargains.

“Bargain Hunting Not Thrilling But—Immensely Profitable”

Ben Graham was twenty-three years old when he began publishing articles in The Magazine of Wall Street. Benjamin Graham on Investing: Enduring Lessons from the Father of Value Investing by Rodney G. Klein offers the reader a cornucopia of these colorful articles. Right from the start, in September 1917, Ben had the generous urge to share what he learned from his work as a statistician, the original name for financial analyst.

His article titles and subheadings convey his early thinking about security analysis, value investing, and shopping for bargains. In January 1919, he published “Bargain Hunting Through the Bond List,” with the subheadings “Gilt Edged Railroad Issues at Attractive Prices” and “Some Cheap Industrial Bonds.” A year later, he wrote “A Neglected Chain Store Issue” with subheadings “The Inconspicuous Merits of McCrory,” “Its Present Low Price Makes It Attractive,” and “Comparison with Its More Pretentious Rivals.” He wrote “Eight Stock Bargains Off the Beaten Track” in the early 1920s and gave his readers “BARGAIN HUNTING NOT THRILLING BUT—IMMENSLY PROFITABLE” around 1925.

One of his first writings, titled “Curiosities of the Bond List,” recommends that investors consider buying Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Bonds. As quoted in Benjamin Graham on Investing: Enduring Lessons from the Father of Value Investing, Ben Graham wrote in September of 1917:

“The Baltimore and Ohio new two-year notes, secured by 120 percent in these Refunding 5s and Reading stocks, yield 5.73 percent, against 5.17 percent for the longer maturity. Their security is at least as good as that of the 1995 issue [a very long duration, taken from Ben’s text], and in the present unsettled bond market they can be relied on to display greater price stability because of their early redemption at par.” (page 15)

Whether he was picking “low-hanging fruit” or simply making good choices, Ben Graham carefully analyzed various options and advised readers to buy the best available bargains.

Hoping to learn more about how Ben Graham applied his skills to the bond market, I open his autobiography, Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street. Rather than bonds, I find him taking an interest in stocks.

Meyer Guggenheim with his seven sons, circa 1895. The Guggenheims made a fortune in the mining and smelting industries.

“My initial success with the Guggenheim Exploration dissolution had given me a strong interest in…arbitrages and hedges—and also in the wider field of undervalued securities, which I staked out as my own particular domain in Wall Street.” (p. 150, circa 1917, age 23)

Securities is another name for stocks. Here, Ben called the stocks he bought “undervalued.” Mr. Munger called Ben’s choice of companies “mediocre.” From his magazine article titles, Ben gives us more unflattering descriptors: “cheap,” “neglected,” “inconspicuous,” and “off the beaten track.”

Dawn of Value Investing

Undervalued stocks were not only Ben’s “own particular domain in Wall Street” but also a crucial component of value investing. A stock must be undervalued—that is, valued below its intrinsic value as a small piece of a business—in order to warrant making an investment in that stock.

“I concluded that money could be made both conservatively and plentifully by buying common stock which analysis showed to be selling too low and selling against the other common stocks which a similar analysis indicated to be overpriced.” (p. 150, circa 1917, age 23)

With these last two quotes, I’m excited to have discovered Ben Graham’s first descriptions of value investing in the Memoirs.

How Does a Value Investor Make Money?

A value investor analyzes companies to find stocks that are undervalued—that is, priced well below their intrinsic value. The investor purchases these stocks and bonds and then holds onto them for the long term, waiting until the sale price rises to reflect their worth. The investor does not give in to herd mentality that dictates they sell when the market goes down, but rather holds onto the shares until the stock price rises and they can sell the stock for a good profit. These profits finance the purchase of more undervalued stocks and bonds, and so the value investor steadily builds equity. Cash on hand from such sales becomes particularly useful during market downturns when stock prices drop, giving investors the opportunity to buy undervalued stocks with a greater margin of safety. I will discuss margin of safety, one of Ben Graham’s key value investing concepts, in a future blog post.

How Warren Buffett Described his Work with Benjamin Graham

If the stocks Ben chose to buy were as mediocre as Mr. Munger suggests, I would think that Ben would have modified his investment strategy as he gained experience. A reliable witness tells us otherwise. After completing his business degree at Columbia under Ben Graham’s tutelage, Warren Buffett was so eager to work with Ben that he offered to work for him for free. Ben refused, stating he needed to save his open positions for Jews, who faced discrimination on Wall Street. However, in 1954, Ben offered Mr. Buffett a job.

Without hesitation, an eager Mr. Buffett uprooted his young family from Omaha and moved to New York. In The Snowball, Mr. Buffett describes to his biographer the work he and his fellow employees did at Graham-Newman. Six financial analysts, including Benjamin Graham, Ben’s business partner Jerome Newman, Walter Schloss, and Warren himself, donned “thin, gray, laboratory-style jackets” and went through “Standard & Poor’s or Moody’s Manual” to look for “companies selling below working capital.” In all fairness to Charles Munger, Ben and Warren talked about their stock picks every bit as disparagingly as Charlie:

“These companies were what Graham called ‘cigar butts’: cheap and unloved stocks that had been cast aside like the sticky, mashed stub of a stogie one might find on the sidewalk. Graham specialized in spotting these unappetizing remnants that everyone else overlooked. He coaxed them alight and sucked out one last free puff.” Warren Buffett, as told to Alice Schroeder, The Snowball, p. 165.

Three of the world’s greatest financial minds described Benjamin Graham’s stock picks in deprecatory terms—“mediocre, cigar butts, cheap, unloved, cast aside, unappetizing, overlooked.” These terms sure don’t inspire confidence.

Was Ben Himself an Undervalued Boy?

Contemplating Ben’s stock choices, I’m hit by the realization that all through his boyhood, Ben felt that people judged him as mediocre. Mediocre or worse—unwanted, worthless, less than. He was consistently undervalued, underrated, and unappreciated by almost everyone in his life. What evidence do I have? Ben had been sorely unappreciated by his mother, Dorothy, who became his sole bulwark against orphanhood after his father’s death when Ben was eight. The saddest, most extreme manifestation of Dorothy’s diminishment of Ben came when he was five years old, when his mother told him she wanted to throw him out the window at birth because he wasn’t a girl. He strove to show her that she made the right choice to keep him. He showed her beyond doubt that he could help her—not only by earning money to bolster her tight budget at after-school jobs like a man, but also the way a girl might have helped, by doing the household chores she asked him to do, including shopping for food.

I get the strong sense that he identified with those undervalued and unsung stocks, the ones no one thought would come to anything. He was sure that—like Ben himself—they would exceed expectations, be a good investment, deliver steady long-term gains, and prove their worth, if you gave them a chance and stuck with them over the long haul.

Ben Saw Himself as “an Underaged, Undersized Youngster”

In February of 1903, shortly before his father suddenly fell ill and died, Ben’s keen intelligence got him skipped into a class of “older and bigger…grammar-department boys.” He was eight years old. His teacher, “blonde and beautiful” Miss Churchill, inspired competition among the boys, “who seemed pleased to be kept after class for extra work, or to help with various chores.”

“All this took place in another universe, far removed from the dreams of an underaged, undersized youngster. But I did love Miss Churchill, because she seemed as sweet as she was beautiful.”

“Underaged, undersized youngster” doesn’t sound so terrible. Yet it was very hard for Ben. At age eight, Ben must have known he was smart—smart enough to skip a grade mid-year—yet he saw himself as too young, small, and inconsequential to compete with more mature classmates for his teacher’s attention and approval. No doubt he saw himself as inferior to his all-male classmates who were bigger, stronger, more socially adept, comfortable with each other and with conducting a heady yet well-mannered flirtation with their attractive teacher. Ben certainly felt undervalued, not only unable to get his teacher’s attention but also unworthy of her high opinion, compared to these fully fledged, dominant males.

This school situation mirrored Ben’s experience in his own family, where he was the underaged, undersized youngest of three brothers. After taking a deep dive into his Memoirs, I concluded in my tenth blog post that “Ben’s older brothers humiliated him for being small and weak and clumsy, excluded him, and hurt him, physically and emotionally.” Ben refrained from saying so directly in his autobiography to safeguard the friendlier connection he’d made with them as adults.

The Hazards of Skipping Grades

Ben’s situation of being one down soon intensified.

“Since this was the fourth time I had skipped, I was barely ten years old when…I was brought up to my new class by the assistant principal. The forty-odd pupils, all boys, took one look at me and burst into raucous laughter.”

Skipping grades—done sparingly in modern times—was both reward and punishment for Ben’s brilliance as a student. According to a recent Time for Kids article, “Skipping a grade lets students take on more challenging schoolwork… but it may be hard for them to make friends. Grade-skippers risk getting bullied for their age or academic skills.” I agree. Visiting an elementary school recently, I saw kids chatting easefully with classmates a head shorter or taller—but these were height differences between same-age students. School friendships practically never span big age differences.

Boys (not Ben Graham) wearing sailor suits, posed with their sisters, circa 1910. Photo courtesy of Davenport Library.

“Instead of the Norfolk suit, de rigueur among these twelve-year-olds, I was still wearing the sailor blouse and pants combination that marked the little boy. They regarded me as some kind of freak, and I began to regard myself with a desperate loathing.”

Boys wearing Norfolk suits and knickers, a popular style in the 1910s. Photo courtesy of Historical Boys” Clothing.

All through the boyhood chapters of his Memoirs, Ben endures one calamity after another. His father dies, his family loses everything, his older brothers mistreat him, and though he works to support his mother, she offers him neither praise nor comfort when he’s hurt. Never does he admit that any of these blows made him suffer—until now.

Self-Loathing

Ben’s poignant confession of youthful misery—“I began to regard myself with desperate loathing”—hurts my heart. Loathing is a strong word—strong enough to convey the painful feelings that must have assailed him: I’m unlovable, unworthy, repellent.

Even if we don’t call his classmates’ behavior bullying, ten-year-old Ben absorbed their ridicule. He saw himself as undeserving of their acceptance and respect. (He also likely endured antisemitic taunts, and on page 15 of the Memoirs, admits he “suffered from general awkwardness” and angered others with his tendency to “run into things and damage them” and sometimes himself, due to poor coordination and absentmindedness.) Unable to see his own goodness, he wound up hating himself. I find this so sad. He was bright enough to skip four grades, yet his exceptional intelligence left him forsaken by his peers.

This was not a passing setback. No one in his life gave Ben unconditional positive regard, the kind of love children need to thrive and grow up to be loving, emotionally connected adults. He didn’t get conditional positive regard either—not from his mother nor his brothers—for his devotion as a family member, his industriousness as a student and wage earner, or his willingness to help his mother whenever she needed chores performed. After his father’s death when Ben was eight, his Uncle Maurice gave Ben’s mother and the three boys a roof over their heads, but he never took a kindly, avuncular interest in his fatherless nephew.

No Friends

Most children—even awkward, brainy, small of stature kids—find friends who like and accept them. Ben lost the neighborhood friends with whom he’d played stoopball and street hockey and “cat” in the relocations following his father’s death. From then on, he had none. Not only was he much younger than his classmates, but the pressure to earn money at after-school jobs left him no time to socialize. In his autobiography, he often tells us that he had many congenial acquaintances but no “chums” or close friends. His reticence and distance, despite his affable nature, were likely due to the “breastwork” or wall he built to protect his heart at an early age. I find it remarkable that, at age sixty-three, he saw that wall and set about dismantling it. He strove to open his heart to a new woman and to family members, including this granddaughter.

For a man with no close friends, Benjamin Graham inspired remarkable devotion in his mentee Warren Buffett. Nearly half a century after Ben’s death, Mr. Buffett spoke of his mentor with tender affection when I visited him in Omaha. Not only did Ben “change his thinking” about investing; he also exemplified the “kindness and generosity” that to this day touches Warren deeply.

Ben Was Determined to Succeed Despite All Obstacles

To show everyone he wasn’t just a small and mediocre boy, Benjamin Graham set out to prove his worth. He would get a good education, complete high school and college at breakneck speed, work nights while attending Columbia and still graduate salutatorian of his class. Earning his diplomas at a much younger age than his fellow graduates did little to convince Ben he was bright and capable, admirable and hard-working—not when his classmates mocked him, his brothers belittled him, and his mother withheld her affection. Having landed a job on Wall Street, he began to buy stocks and bonds that were selling for less than they were worth, just as Ben himself was deemed less than he was worth.

Buffett Hits the Jackpot With a Graham “Cigar Butt” Pick

I find it fascinating to leapfrog thirty years ahead to the 1950s, when Ben Graham and Warren Buffett worked near each other in Ben’s office, hunting for the next “cigar butt” company. In Brett Gardner’s new book, Buffett’s Early Investments: A new investigation into the decades when Warren Buffett earned his best returns, Gardner analyzes ten companies that Warren Buffett chose to invest in in his twenties, using only information that was available to Buffett at the time. I smile to picture those two lions, Graham and Buffett, coaxing a tidy payoff for Warren from a mouse of a company.

Warren Buffett in 1962 and Benjamin Graham in 1947. Imagine these kings of the jungle with lion manes! Photo courtesy of Business Insider /AP Photo

“Warren was not proud; he also felt honored to borrow ideas from Graham…One day he followed up on an idea of Graham’s, the Union Street Railway. This was a bus company in New Bedford, Massachusetts, selling at a big discount to its net assets…[Warren Buffett] made about $20,000 profit on this one stock in just a few weeks. No one in the history of the Buffett family had ever made $20,000 [$236,408 in 2025 dollars] on one idea. In 1955, that was several times more than the average person earned for a whole year’s work.” Warren Buffett/ Alice Schroeder in The Snowball, p. 174

Union Street Railway electric streetcar, pictured in Fall River, Massachusetts, 1950s. Courtesy of Umpteen Postcards.

The Triumph of the Undervalued Boy

“He could not understand how others, including those who loved him dearly, would so often wound him, with nonchalance or even with malice.”

Ben Graham wrote those words in his “Self-Portrait at Sixty-Three,” included as an Epilogue in the Memoirs. He reveals that his boyhood wounding caused him to build a wall around his heart. People who doubt their own worth—who don’t see the goodness inside themselves because their parents and other family members don’t treat them as worthy of love—often struggle in their lives. My grandfather certainly struggled with love and marriage. Yet he was able to hitch his fierce drive to his superb mind, his courage to his fear, his suffering to his strength—in order to create a new way of investing that, according to distinguished Wall Street Journalwriter Jason Zweig, “still bedazzles readers more than 70 years later.”

Valuing Himself

Ben Graham sought out the lesser-known stocks that others overlooked. The ones no one thought would amount to anything were the ones he bought for his clients and highlighted in his articles for investors. The unappreciated and undervalued math whiz became the security analyst who championed unappreciated, undervalued stocks—stocks that, like him, would surprise everyone by ending up a worthwhile investment if given a chance to shine.

By the time Benjamin Graham claimed “undervalued securities” as his personal domain, he was well on his way to creating value investing, and he was making a start on valuing himself. Benjamin Graham taught Warren Buffet to see the beauty and goodness in undervalued stocks. Ben would need more time to see the beauty and goodness in himself.