Warren Buffett’s Thanksgiving message—announcing that he’s stepping down from the helm of Berkshire Hathaway and “going quiet”—casts new light on the depth of his bond with Benjamin Graham. It reminds us that Buffett not only mastered Graham’s principles of value investing, becoming the world’s most celebrated investor, but also absorbed the values and wisdom Graham imparted. Both men lived out those ideals, each in his own distinct way.

Above, Mr. Buffett is pictured receiving the Medal of Freedom from President Obama in 2011—for bringing integrity to his work and, in the president’s words, “devoting the vast majority of his wealth to those around the world who are suffering, or sick, or in need of help.” Five years before, Mr. Buffett made the commitment through The Giving Pledge to give all but 1% of his net worth to charitable causes. Since then his net worth has soared to over $150 billion, enough to make a difference in alleviating human hardship around the world.

Friendliness Personified

In his Thanksgiving message, Mr. Buffett addresses his remarks “to my fellow shareholders,” then proceeds to charm them with his characteristic wit and all-embracing friendliness—friendliness that seems to welcome every reader with warm handshake. Indeed, he uses the word “friend” or “friendly” a dozen times in the letter. He also utilizes the word “wonderful” to describe certain people, including my grandfather:

“In 1954 I took what I thought would be a permanent job in Manhattan. There I was treated wonderfully by Ben Graham and Jerry Newman and made many life-long friends.”

When describing himself at 95, Buffett likewise employs “wonderful” to characterize the people he works with at Berkshire Hathaway.

“To my surprise, I generally feel good. Though I move slowly and read with increasing difficulty, I am at the office five days a week where I work with wonderful people.”

I had the pleasure of meeting some of those “wonderful people” during my three days working in his office, back in 2022. Mr. Buffett had invited me to Omaha to go through his nine large files of papers pertaining to my grandfather, in order to compile the Benjamin Graham papers, now housed in the Archival Collections of Columbia University’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library in New York City. Every one of Mr. Buffett’s employees I spoke with, in the hall or modest break room where we ate our bag lunches, smiled when they talked about their jobs. They spoke fondly of their twenty-five plus years working at Berkshire-Hathaway—a company with no HR department, they told me, because no one quits or gets hired. I could see that they enjoyed working with their fellow employees, including their famous boss.

Besides “wonderful,” I found more words in Mr. Buffett’s letter that highlight the goodness he sees in those around him: “kind,” “generous,” and “grateful.” He calls people “heroes” and “the best.” What strikes me is that the very qualities he admired in my grandfather during my visit with him—kindness and generosity—are the same values Warren Buffett himself embodies at age 95.

Everyone Deserves Our Respect and Compassion

Warren Buffett seems to have integrated these values into his inner being to an extraordinary degree. Here, along with a remarkable humility that entails admitting his mistakes and learning “how to behave better,” he expresses appreciation for others along with compassion for those less fortunate:

“I write this as one who has been thoughtless countless times and made many mistakes but also became very lucky in learning from some wonderful friends how to behave better (still a long way from perfect, however). Keep in mind that the cleaning lady is as much a human being as the Chairman.”

I love that he acknowledges his own fallibility and efforts to grow. His humility carries me to his last sentence, which I find to be profound. In his folksy style, he conveys to us—his admirers and shareholders—his view that all humans have dignity and worth. All people deserve happiness. Regardless of their financial or social status, they merit our empathy and respect. You may think I’m taking this too far, but I feel, at the heart of his all-encompassing benevolence, an abiding love for his fellow human beings.

Don’t Worry, You’re in Good Hands

Warren Buffett chose Greg Abel to be his successor as CEO of Berkshire-Hathaway. The two men continue to work closely together in the final days before Mr. Buffett’s retirement. Photo courtesy of Omaha World-Herald.

Warren Buffett’s benevolence extends to the person who will succeed him as CEO of his trillion-dollar company. His praise begins with a trio of short quips:

“Greg Abel will become the boss at year end. He is a great manager, a tireless worker and an honest communicator.”

But Mr. Buffett has more to say about Mr. Abel—while offering another helping of his signature humility:

“Greg Abel has more than met the high expectations I had for him when I first thought he should be Berkshire’s next CEO. He understands many of our businesses and personnel far better than I now do, and he is a very fast learner about matters many CEOs don’t even consider. I can’t think of a CEO, a management consultant, an academic, a member of government—you name it—that I would select over Greg to handle your savings and mine.”

I sense Mr. Buffett giving his shareholders the assurance they need that they’re in good hands—that their investment in Berkshire will continue to remain stable and grow in value. I smile to remember my uncle Buz (Benjamin Graham’s youngest son) telling me what Ben told Buz’s mother Estelle and their close friends and cousins the Sarnats regarding who should succeed him as their investment advisor. Ben was stepping down from running his hedge fund—in fact, he had retired entirely from investing at the age of 65. He told his closest family members to “invest with Warren.”

Unluckily for me, my mother—Ben’s oldest daughter—didn’t follow his advice. Buz’s mother Estelle Graham, on the other hand, did. Estey bought shares of Berkshire-Hathaway because Warren Buffett and his wife Suzie were her good friends. In this regard, I discovered two letters from Estey to Warren in Mr. Buffett’s files—letters he graciously indicated I was free to take home as keepsakes.

In this second note, Estey writes to Warren about “making an additional investment,” revealing not only her warm relationship with the Buffetts but also her recent visit with David Dodd, Ben Graham’s co-author on Security Analysis and his longtime teaching partner at Columbia Business School.

I can’t help but smile at the image this letter evokes—my Grandma Estey investing with Mr. Buffett in a way that feels so personal and human. It’s amazing that this Warren she trusted with her investment was twenty-nine years old, soon to turn thirty on August 30, 1960. The “Ben Graham” circled atop the letter resembles the handwriting in this thank you note and was likely written by Mr. Buffett himself to indicate where to file it. Though I’m not privy to the inner workings of Mr. Buffett’s company, I sense is that both Ben and Warren were wise in their choice of successors.

Champions of Shareholders Rights

While expressing his confidence that Berkshire will continue to thrive after he gives up the reins, Mr. Buffett adds a note of caution against amassing money for money’s sake.

“Berkshire has less chance of a devastating disaster than any business I know. And, Berkshire has a more shareholder-conscious management and board than almost any company with which I am familiar (and I’ve seen a lot). Finally, Berkshire will always be managed in a manner that will make its existence an asset to the United…Over time, our managers should grow quite wealthy—they have important responsibilities—but do not have the desire for dynastic or look-at-me wealth.”

Two points stand out. First, Mr. Buffett’s policy of “shareholder-conscious management” shines throughout the letter. No one can doubt that he cares deeply about the well-being of his shareholders. His mentor—my grandfather, Ben Graham—pioneered the principle that a company’s managers and board members owe their shareholders both appreciation and a fair share of the pie.

As a young man, my grandfather took on Standard Oil in the Northern Pipeline Contest and, after setbacks that might have stopped a less determined soul, ultimately triumphed over a corporate Goliath. He won a seat on Northern Pipeline’s board and succeeded in pushing the company to return its excess cash to shareholders. An early champion of shareholder rights, he helped set a precedent that, a century later, Mr. Buffett has elevated to a new level.

Long ago, Mr. Buffett reached a point where he neither wanted nor needed more money. He had enough—and pledged to give 99% of it to charity. What kept him applying his extraordinary mind to acquiring new companies and shaping Berkshire into the enterprise it is today was simple: his shareholders.

Mr. Buffett Regards his Shareholders as Partners

In The Warren Buffett Shareholder: Stories from Inside the Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting, editors Lawrence Cunningham and Stephanie Cuba tell us that Buffett’s annual shareholder meeting has grown from a thousand in 1989 to 40,000 in 2025. In their book, the editors quote Jason Zweig, commentator of Ben Graham’s The Intelligent Investor:

“Buffett has thought a lot about why so many people come to his meetings. ‘First, they come to have a good time,’ he tells me afterward. ‘Second, they come to learn. And they really feel as if they’re partners in the enterprise.’” Jason Zweig

At his annual meetings, Warren Buffett fostered a warm, caring atmosphere by addressing thousands of shareholders in the same folksy, humorous style that characterizes his Thanksgiving letters. Radiating good will, he brought them up to date on his thinking and decisions, treating them as he sees them: valued partners in his enterprise.

Graham and Buffett Chose to Live Simply

In his recent letter, Mr. Buffett goes beyond reporting on Berkshire’s financial condition. He holds his shareholders in such regard that he shares with them a set of life lessons—some of which he learned from my grandfather, Ben Graham. For example, Mr. Buffett cautions against accumulating “dynastic” wealth, having concluded that “look-at-me” riches do not bring happiness. Like my grandfather before him, Mr. Buffett chooses to live simply.

Benjamin Graham rose out of poverty believing that “large earning and large spending” would signal success. He did, for a time, rent luxurious quarters at the Beresford in Manhattan, but he gave them up after the Crash. Once he closed his Wall Street office in 1954, he gravitated toward a simpler life. He moved to California and eventually left his Beverly Hills home behind, opting instead for two small dwellings, each set in a beautiful place: a cottage in Aix-en-Provence, where I stayed with him in 1971, and a modest two-bedroom apartment in La Jolla, California, where I often visited and talked with him on his honey-yellow striped couch. His sofas were nothing fancy, and I was surprised to realize, decades later, that I had unknowingly bought furniture upholstered in those same fabrics pictured here for my own home.

Warren Buffett follows Ben Graham’s example of living simply. He still resides in the Omaha home he purchased for $31,500 sixty-seven years ago.

Warren Buffett purchased this brick-and-stucco home for $31,500 in 1957, at age 28. Eight years later, in 1965, he took control of Berkshire Hathaway. He has lived in this same house for nearly seven decades. Photo courtesy of Omaha Heritage Preservation.

“In 1958, I bought my first and only home. Of course, it was in Omaha. located about two miles from where I grew up…and a 6-7-minute drive from the office building where I have worked for 64 years.”

He drives a 2014 Cadillac XTS that he bought at a discount after it sustained cosmetic damage in a hail storm. Though the legendary investor allows himself the luxury of traveling by private jet, he owns only a fraction of the aircraft. Berkshire owns the company, NetJets, making the arrangement financially sensible for both him and his shareholders.

Beyond Money: Lessons from the Oracle of Omaha

I find myself marveling at how Warren Buffett uses his annual shareholder letter—one of the most widely read business documents in the world—as a platform not just for discussing investments, but for offering guidance on how to live a good life. His writing drifts toward wisdom that transcends finance. You expect economic forecasts; you end up with moral clarity.

Buffett has long reminded readers that the things we typically chase—wealth, fame, power—rarely bring real fulfillment. As he once put it, “Success is having people love you who you want to have love you.” That’s a definition of wealth that cannot be measured in dollars.

Mr. Buffett frames greatness in simple, human terms: You don’t need vast resources to make a meaningful difference. A quiet act of generosity, a moment of patience, the simple decision to treat someone well—these are accessible to anyone yet invaluable to everyone. Kindness, he suggests, costs nothing and changes everything.

“Greatness does not come about through accumulating great amounts of money, great amounts of publicity or great power in government. When you help someone in any of thousands of ways, you help the world. Kindness is costless but also priceless. Whether you are religious or not, it’s hard to beat The Golden Rule as a guide to behavior.”

Kindness and Generosity: From Ben to Warren

Mr. Buffett’s words move me deeply, because he told me in person that my grandfather was kind and generous toward him when he was a young man—kind and generous in ways that stuck with him all his life. So affected was Mr. Buffett that he embraces kindness and “do unto others” as precepts that guide him toward happiness and a sense of fulfillment.

In 1954, my grandfather offered Warren Buffett, age 24, a position in his Wall Street firm. Mr. Buffett left Omaha behind, traveling to New York with his pregnant wife Suzie and young daughter Susan in order to realize his dream—to work alongside his former Columbia professor, Benjamin Graham. “Ben treated me kindly,” Mr. Buffett told me, emotion visible on his face. “Same as he treated everyone in the office.”

After Ben died, Warren Buffett wrote these words about his mentor in The Financial Analysts Journal in 1976:

“Generosity was where [Benjamin Graham] succeeded beyond all others. I knew Ben as my teacher, my employer and my friend. In each relationship—just as with all his students, employees and friends—there was an absolutely open-ended, no-scores-kept generosity of ideas, time and spirit.”

Contemplating this transmission of kindness and generosity from teacher to student, employer to employee, mentor to mentee, fills my heart with gratitude. How amazed my grandfather would be to see his student Warren Buffett, now a revered figure, embodying those stellar qualities—and telling his granddaughter (me!) that Ben himself inspired those values. Not only does Mr. Buffett exemplify generosity and kindness, but he transmits them to everyone who reads his Thanksgiving message and emulates him around the world.

Kindness and generosity need not take the form of authoring groundbreaking investment guides that help protect the financial wellbeing of future generations, as Benjamin Graham did, nor of giving away billions to charity, as Warren Buffett has done. Each of us can find our own ways to be friendly and kind, starting with trying to help people and expressing thanks to those who help us. We can look for and appreciate the good in people—a child, parent, partner, stranger, or friend. We can volunteer at a school, library, or food bank. We can try to get along with people. We can help birds, butterflies, dogs, kittens, pigs, children, elders, whomever opens our heart. Recently, the driver of a hauling truck did me a kindness; he volunteered to lift heavy slabs of rose fieldstone for me at a landscape supply yard, enabling me to choose stepping stones for my garden. Another act of generosity I recently witnessed: a friend collected donations for a struggling school in Tanzania.

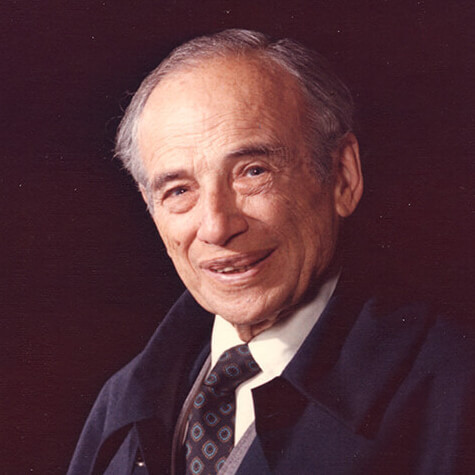

Warren Buffett at 95. He established the Buffett Partnership Ltd in 1965 with $105,000 in capital. On the verge of retiring from his job as CEO of Berkshire-Hathaway, he’s now the world’s most generous philanthropist. Photo courtesy of Bloomberg / Getty.

Wealth is for Giving to Others

Mr. Buffett stands as a towering figure in our greed-ridden world: a rich man who doesn’t need or want more money for himself, just for others. He directs his efforts toward enlarging his shareholders’ nest eggs and donating to charities that improve the lives of people suffering hardship. He expresses confidence that that “very special group”—his shareholders—will, in turn, practice altruism toward others.

“Berkshire’s individual shareholders are a very special group who are unusually generous in sharing their gains with others less fortunate.”

In a sector of America that might have been a bastion of greediness and materialism—qualities that foster discontent and often harm the individuals and their families who get caught up in them—he models serving others, living simply, and giving to those in need—the very qualities that bring inner strength, happiness, and meaning. In 2025, Mr. Buffett donated $6 billion in Berkshire Hathaway stock to five foundations, the largest single charitable gift of his life. His lifetime donations now exceed $60 billion.

Reflecting on the last hundred years of value investing, I see my grandfather Benjamin Graham rising from boyhood poverty, intent on making “large earnings” to support his widowed mother and growing family. Ben used his brilliant mind to invent security analysis and value investing, and rather than keeping his innovative investment strategies to himself, he set out to share them—with his public via articles and his iconic books, and with his students at Columbia School of Business. His star student, Warren Buffett, learned these analytic methods from the “father of value investing” while absorbing Ben’s qualities of kindness, generosity, and friendliness—qualities that bring peace of mind and well-being.

Now Warren Buffet, a giant of modern finance at 95, not only embodies those qualities but shows us how to lead a life rich with giving while living simply and treating others with decency, calm, and good will. Regarding his commitment to donating 99% of his wealth, Mr. Buffett gives his children, now in their late sixties and early seventies, each managing a charitable foundation, a resounding ovation to help “dispose of what will essentially be my entire estate”:

“All three children now have the maturity, brains, energy and instincts to disburse a large fortune…All three like working long hours to help others, each in their own way.”

Who could have imagined that my grandfather—an immigrant boy who once hauled barrels of cinders from a coal furnace and pushed a cart laden with glass bottles of milk—would one day mentor and inspire the titan of American business who has become the largest charitable donor in history?