In 1932, Benjamin Graham faced a devastating financial reckoning. The aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash had wiped out seventy percent of both his personal fortune and the assets held in the Benjamin Graham Joint Account. The loss wasn’t just his own—it carried a far deeper weight. He felt responsible not only for his wife, children, and widowed mother, but also for everyone who had entrusted him with their money. These weren’t wealthy investors who could afford to take a hit; they relied on him to protect their life savings. His own failure stung, but the heavier burden was knowing how badly he had failed those who trusted him.

In his autobiography, Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street, he recalls becoming a “near-millionaire” during the “great bull market of the 1920s.” He achieved this by developing innovative strategies for selecting stocks and bonds—pioneering approaches such as arbitrage and value investing.

“The Benjamin Graham Joint Account started with $400,000. Three years later, our capital was around 2 ½ million, most of the addition from profits; a good deal of it belonged to me as the reinvestment of my ample compensation plus the earnings on my growing capital.”

Hubris Before the Fall

These sums were impressive enough to quiet the cutting remarks of Ben’s brothers—and to inspire his mother, once disappointed he hadn’t been the daughter she desired, to regard him with new admiration. He even finally admitted some pride in his own accomplishments.

“At thirty-one I was convinced that I knew it all—or at least I knew all I needed to know about making money in stocks and bonds—that I had Wall Street by the tail, that my future was as unlimited as my ambitions, that I was destined to enjoy great wealth and all the material pleasures that wealth could buy. I thought of owning a large yacht, a villa at Newport, racehorses…I was too young to realize that I had caught a bad case of hubris.”

His drive for wealth and success was fueled, at least in part, by a deep yearning to be loved—to feel worthy. But by 1932, he had lost a staggering sum. If financial success had once been the measure of his self-worth, now he felt diminished. Like so many on Wall Street, he hadn’t foreseen the Crash, and the consequences of his misjudgments were disastrous. It’s no surprise that, in his Memoirs, he would later recall feeling “near-despair.”

Ben’s Novel Compensation Arrangement

Ben’s despondency wasn’t just an emotional response to failure—it was rooted in stark financial reality.

In 1926, Ben launched the Benjamin Graham Joint Account under an unusual compensation model: He would take no salary, but instead earn up to fifty percent of the profits on a sliding scale. During the booming 1920s, this arrangement worked beautifully in his favor. Thanks to his remarkable investment performance—and a steady stream of capital from “new friends” eager to ride the wave of his success—the fund soared to $2.5 million. In the Memoirs, Ben pinpoints the problem as follows:

“His agreement with his investors stipulated that “any losses be made up in full before we receive any compensation.”

Ben was responsible for supporting his wife, three children, and his mother, yet he couldn’t draw a cent from managing the Joint Account until he had repaid his investors’ losses.

Can You Believe This?

I shake my head in amazement. Does that mean that had I been alive in 1926, I could have invested in my grandfather’s Joint Account and been assured that not only would I make a nice profit in good times, but that after the Crash when the value of my investment sank to a dire low, my fund manager—the legendary Benjamin Graham himself—would make up my losses? Apparently, it did mean that.

What Does Warren Buffett Say?

I found this so astonishing that I looked to Mr. Buffett for elucidation. In his biography, The Snowball, Mr. Buffett writes:

“In 1932, [Graham’s Joint Account] was down from $2.5 million to $375,000. Graham felt responsible for recouping his partners’ losses.”

That states the bald fact, but makes it sound as if Ben wanted to recoup his investors’ losses solely out of the goodness of his heart.

I asked Mr. Buffett about this when I visited him in Omaha in 2022. He clarified that my grandfather didn’t repay those losses by writing checks to each investor. Instead, he worked tirelessly—and with remarkable skill—to rebuild the fund to its pre-Crash peak. As a result, those who kept their money with him ultimately recovered everything they had lost. I’m deeply moved by the fact that my grandfather managed the fund for five years without taking a cent in compensation, all to make his clients whole. The “Chronology” at the back of the Memoirs captures it best with a brief but powerful entry at the close of 1935:

“All Depression Losses are made good.”

All Work and No Pay

I can’t fathom how Ben earned a living for those five years of no pay, though his Memoirs do reveal his “many activities” from 1930–1932: writing articles for Forbes magazine, teaching at Columbia School of Business, writing Security Analysis with David Dodd (to be published in 1934), and giving testimony as an expert witness on cases of valuation.

Adopting a Modest Standard of Living

Ben’s traumatic experience of acute financial loss had a life-changing effect on him. He gave up the materialistic values of his young manhood—the idea that “large earning and large spending” were “the primary mark of success.”

“I quickly convinced myself that the true key to material happiness lay in a modest standard of living which could be achieved with little difficulty under almost all economic conditions….It became my firm resolve never again to be maneuvered into ostentation, unnecessary luxury, or expenditures that I could not easily afford.”

Ben goes on to admit that he took his drive to economize “much too far.” He confesses to riding the subway instead of taking a taxi—even when he was running late—and routinely ordering the least expensive entrée on the menu. For his weekly dinners with his mother, he often chose Chinese restaurants, presumably the least expensive eating establishments. He emphasizes that he mostly denied himself costly items, while making a conscious effort not to stint on others or appear “miserly” in his treatment of them.

Benjamin Graham, his third wife Estelle Graham, and their son Benjamin “Buz” Graham, Beverly Hills, California, circa 1956.

Rock Star of the Financial World

If Ben Graham was so committed to avoiding “unnecessary luxury,” why did he purchase two costly homes—one in Scarsdale in the early 1950s, and later, after selling that house, another in Beverly Hills in 1956? First, I’m certain that his third wife—my grandmother Estelle—strongly influenced the decision. They were raising a child together, my uncle Buz, and a spacious, beautiful home would have been important to her. Second, by that point, Ben had experienced an extraordinary run as a fund manager from 1936 to 1956. Forbes would later call him a “rock star of the financial world” and rank him among the top five mutual fund managers of all time, citing an impressive twenty-one-percent annual return over two decades. Those earnings gave Ben more than enough means to purchase expensive homes with no difficulty whatsoever. True to his principles, Ben avoided expenditures he couldn’t easily afford.

Entrance canopy of The Beresford, at 211 Central Park West. Benjamin Graham and his family moved into the Beresford in October 1929. Photo courtesy of CityRealty.

Bye Bye Beresford

But in 1929, he couldn’t afford the Beresford. In my last post, we saw how Benjamin Graham tightened his belt and wasted no time in moving his family into a less expensive apartment, shedding the burden of the Beresford’s extravagant lease. Still, my curiosity endured. On a visit to New York, I stepped out of the Museum of Natural History and found myself facing the entrance of my grandfather’s grandest former abode. I felt an irresistible urge to see the Beresford’s nineteenth and twentieth floors, where Ben witnessed the Crash at age thirty-five, and my mother—just nine years old at the time—played with the rabbit that cost her parents a small fortune in legal fees. A fiercer battle broke out at the Beresford in 1963, when violinist Isaac Stern clashed with his upstairs neighbor over renovations that caused “unbearably loud noises.”

In 1929, my grandfather was renting two apartments for what was then a whopping $11,000 per year, and in 1998, Jerry Seinfeld bought Stern’s apartment for $4.35 million. Wowza. Since my granddad’s time, the price of admission and the star power of the residents have certainly skyrocketed.

Lobby of the Beresford. Photo courtesy of CityRealty.

Having failed to charm the stern-faced doorman into letting me step into the lobby, much less Ben’s apartments, I ease my disappointment by uncovering more alluring Beresford facts. Actress/writer Phyllis Newman and her husband hosted glittering parties in apartment 19E—a mere fraction of my grandparents’ palatial duplex—where the likes of Lauren Bacall, Glenn Close, Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, and Groucho Marx once hobnobbed. I even came across these 2019 photographs of the interior of Newman’s apartment—the very rooms where my family members once walked.

A room in the Newman-Green apartment. Photo by Denis Vlasov, The New York Times, November 22, 2019. Courtesy of Daytonian in Manhattan

Another room in the Newman-Green apartment. Photo by Denis Vlasov, The New York Times, November 22, 2019. Courtesy of Daytonian in Manhattan.

The Hardest Pain of All

Swept up in the glamour of the Beresford, I’m blindsided by the suppressed truth that suddenly surfaces. Ben’s seventy percent loss of his fortune in the 1929 Crash was devastating enough. But Benjamin Graham had suffered a more profound blow—one no amount of recovery or future success could mend.

“In early March of [1927] we returned from a vacation in Florida to find that [our eldest son] Newton was suffering from ear trouble. We called in Dr. Friesner, the great ear specialist of Mt. Sinai Hospital. He diagnosed our child with mastoiditis, which required an operation. After the operation, spinal meningitis set in and Newton died on April 20, 1927.”

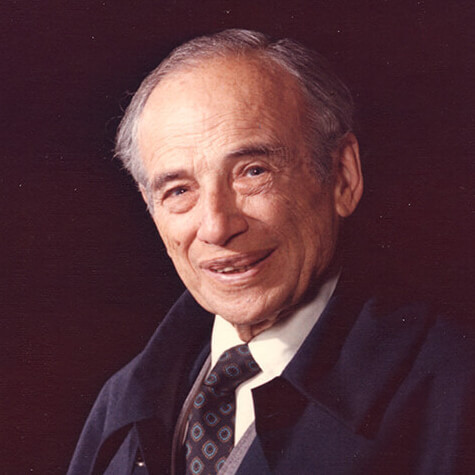

Ben’s beloved firstborn son, Newton, pictured atop this post, was eight years old. My uncle Newton would have turned nine on May 12. His full name was Isaac Newton Graham, named after Ben’s father Isaac who died when Ben was a boy.

Portrait of Isaac Newton Graham. My mother saved this portrait of her dear brother all her life. She gave the photograph to me, and I gave it to her youngest brother, Buz. (Buz was born in 1945, eighteen years too late to have met his brother Newton.) Buz passed in March of this year and Newton’s portrait still hangs a place of honor in Buz’s study.

To my mother, Marjorie—two years younger than Newton—this “great tragedy” remained a vivid and sorrowful memory, even as she recalled it to me at the age of ninety. Her enduring love for her lost brother was palpable.

“Newton looked out for me. I was a kid who misbehaved. I made too much noise, stayed awake when I was supposed to go to bed, woke up too early, moved too fast, wanted to do things my way, and didn’t obey Fraulein [the children’s governess] like the other kids did. Newton looked out for me. If I got into difficulty or trouble, he’d try and mostly could fix it—with other kids and with our parents.” Marjorie Graham Janis, Newton’s sister, August 17, 2010.

I was overcome with the magnitude of her loss at such a tender age. My little rebellious mother lost her closest companion and protector. “What was he like?” I asked.

“Newton was a quieter person, while I was loud and active. We did things together all the time, I can’t remember what. We had a closeness I always wanted again. He was very bright and highly intelligent, thoughtful and loving. Our parents recognized him as a kind and caring boy, who took responsibility for his younger siblings [Marjorie, age six, and Elaine, age one]. His example taught me to change my behavior and become the eldest who took care of the younger ones. The year after Newton died, antibiotics came out. He would have had the chance to survive his ear infection, sinusitis, and meningitis.” Marjorie Graham Janis, 2010

My mother was correct that Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928, but antibiotics didn’t become widely available until the 1940s.

He Was Her Shield, Then He Was Gone

I’m struck by a passage in the Memoirs where Ben describes visiting Newton at Mt. Sinai Hospital during his final weeks and telling Newton that his sister Marjorie had received “the blue ribbon for the best work in her class.” I believe my mother was in first grade.

“Newton’s face lit up, and then he said seriously: ‘You don’t appreciate Margie properly. She really is very smart.’”

Sadness crashes over me when I contemplate the generosity of this eight-year-old boy, lying in a hospital bed, too ill to attend school, enduring post-surgical pain, mustering his strength to exhort his parents to give his younger sister—my mother—more appreciation. He was insightful enough to know that her intelligence, not her character, might be the thing to persuade them to see her in a more favorable light.

Newton’s death broke the Grahams’ hearts. Of Newton’s funeral, Ben writes:

“We weeping parents…threw the last handfuls of earth over his little grave.”

That might be the last time Ben let himself weep for Newton.

Private Pain Fueled a Public Fight

It hits me that in January of 1928, when Benjamin Graham confronted Standard Oil and Northern Pipeline—and won!—he had suffered the loss of his son just eight months before. I reflect on the tenacity, power, and courage he displayed to right a wrong. Could it be that he channeled his buried emotions—anger, outrage at the injustice, the deep shame and sorrow of being powerless to save Newton—into that battle?

Ben’s Boyhood Loss Shaped Him

Readers of this blog know that Ben suffered a tragic loss when he was eight years old—the death of his father Isaac to pancreatic cancer. That sudden death—shocking for a young boy—had a profound effect, not the least on his way of coping with future losses. He came to believe that expressing one’s grief can be fatal.

Bernard Grossbaum resided in London, England. Bernard was the father of Isaac Grossbaum and grandfather of Benjamin Graham. Photo courtesy of Debbie Goodrich.

Here’s what happened. Ben had met his paternal grandfather, Bernard Grossbaum, a “bearded patriarch” who resided in London, on a trip to England the summer he was seven. Some months later, a telegram announcing his death arrived from London.

“I remember my father reading [the cablegram] and straightway bursting into loud lament.”

Ben’s father Isaac engaged in demonstrative grieving. On the heels of his lamentations, Isaac fell into rapid decline.

“When my grandfather died, Father’s health was already sadly impaired…”

But in Ben’s young mind, Isaac’s grief killed him. Ben wasn’t entirely wrong. Bernard’s death deepened the financial strain Isaac was already under, burdened as he was with supporting his New York family and his very large family in London.

In stark contrast, Ben’s mother neither openly mourned her husband nor helped her sons navigate their own grief after his sudden death. She spoke of their father rarely—if ever. As Ben observed:

“She made no parade of wifely devotion and fidelity to the memory of her Isaac.”

Portraits of Benjamin Graham’s parents: Dorothy Grossbaum and Isaac Grossbaum. Photos Courtesy of Laura Steele.

Ben’s father Isaac grieved deeply and was soon stricken with a fatal cancer. His mother Dorothy, by contrast, did not grieve—and survived to raise her three sons. The unspoken lesson: To mourn is to die. No wonder Ben grew up to be a man who avoided grief altogether, adopting his mother’s style of stoic endurance and soldiering on.

“The loss of my first-born son in 1927 was a bitter blow, the more staggering perhaps it came so suddenly in the midst of dazzling prosperity. There were also strains developing in my marriage…I was too ready to accept materialistic success as the aim and goal of life and to forget about idealistic achievements.”

Not only did Ben abandon dreams of idealistic achievement, but—after weeping at Newton’s grave—he fortified the defenses he would carry into his sixties. His heart retreated behind its “breastwork” or wall, and his brilliant mind turned toward conquering the near-poverty of his fatherless youth, soon to be compounded by the ruinous losses he endured after the Crash.

How Did Newton’s Death Affect Ben?

Many of us find solace by praising the admirable qualities of our deceased loved ones, but Ben crossed the line into extreme idealization. In his Memoirs, he recalls the epitaph he and Hazel chose for Newton’s grave.

“The little footstone bears the words: ‘SWEETEST, BRAVEST, MOST BELOVED CHILD.’”

In all honesty, those words make me queasy. No child should be burdened with being always sweet or endlessly brave, with no room for anger, fear, or imperfection. And no sibling should have to live in the shadow of a perfect, favored child—especially one lost too soon.

My grandparents couldn’t have known the harm such comparisons might cause, but sadly, the consequences were wounding and real. I’ll explore those in a future post.

My heart aches with compassion for them—and for their surviving children. The loss of a child can shatter even the strongest marriage. Ben, in his words above, admitted that his relationship with Hazel was already strained. They spoke of beginning “a new and better life together” but were unable to repair the many sources of unhappiness between them. Divorce in 1930s New York was rare, socially stigmatized, and legally difficult, but it’s not surprising that nine years later, their marriage would end. Ben Graham writes:

“A great grief and the best of intentions are not enough, alas! to correct deep-seated conflicts between a husband and wife.”

I sense that Ben’s decision to rent the luxurious lodgings at the Beresford embodied his dream that the trappings of wealth—sumptuous surroundings, the commotion of a “troupe of servants,” and the task of furnishing room after opulent room—might save them. Or if not save, at least distract Hazel, if not himself, from the grief.

Ironically, the Crash and ensuing Depression served to distract Ben from his emotional pain. His hands were full coping with financial pain—his own and that of the investors in his hedge fund.

What Good is Money, Anyway?

Wealth protects people from the harsh consequences of untreated injury or illness, from hunger, cold, and exposure to the elements. It provides spacious homes, abundant privacy, and the freedom to live on one’s own terms. But for Ben, in that time and place, these promises of wealth didn’t hold true. Surrounded by a host of servants—including a governess and a personal valet—and his wife and three children, Ben found himself with no privacy. The neighbors who took offense to his children’s pet built an unsightly wall that robbed him of the pleasure of enjoying the view from his own terrace.

Can Money Mend a Broken Heart?

No, I don’t believe it can. In fact, greed—the relentless drive to accumulate wealth beyond what’s needed for a comfortable life—does the opposite. Choosing long work hours over time with loved ones, chasing instant gratification and status through consumerism, and prioritizing profit over presence don’t protect us from pain; instead, these choices deepen our isolation. They cut us off from connection with others, leave us lonely when we need support, and distance us from love, our deepest values, and the very things that help our hearts heal and flourish.

I’ve come to see that extraordinary intelligence—like the kind my grandfather possessed—can lead to groundbreaking innovations in a chosen field, but doesn’t equip a person for transformative mourning. That deeper form of grieving allows bereaved parents to truly feel their loss, accept support, adapt to a changed life, and somehow find a way to go on without their child.

I wish, with all my heart, that my grandfather had been able to use his resources—before the Crash left him in financial ruin—to seek out whatever professional help existed in 1927 when Newton died. I wish Ben had been able to open up emotionally, both to himself and to those around him: to bring his family close to cry in each other’s arms; to support his children, including my mother, as they processed their own grief; to comfort his wife, my grandmother Hazel; and to bond tenderly with the new son born in April 1928, just a year after Newton’s death.

But he received no help. And tragically, none of that was possible for him.

All of Us Need Help in Times of Loss

It takes courage and grit to develop the kind of emotional intelligence needed for true healing. I’m grateful that today, bereaved family members have access to therapists and counselors, bereavement groups, countless books and memoirs, Anderson Cooper’s “Love is What Survives” podcasts, and even movies and TV shows—from the Oscar-winning Ordinary People to the seriocomedy Stick—all offering some consolation and reminding them they’re not alone in their grief.

Later in Life, Ben Abandoned Wealth to Embrace What Truly Matters

No matter how much wealth Benjamin Graham amassed through his inspired investing strategies in the 1920s, he couldn’t save his son. He couldn’t shield himself or his family from the saddest of sorrows—the death of a child.

Ben first began to understand this lesson when he gave up the expensive Beresford, but it wasn’t until he suffered another terrible family tragedy in his sixties that he looked inward and asked himself what mattered most. That turning point, briefly mentioned in About Ben Graham and to be explored in detail a future blog post, prompted him to make profound life changes: abandoning investing and the pursuit of wealth in favor of a simple life as a Classics scholar with a heart open to love.

Thankfully, a century after my uncle Newton’s passing, immunizations and antibiotics now protect countless children whose lives might have been lost in the 1920s. To the parents who still suffer the heartbreaking loss of a child today—and to the siblings who lose a dearly loved brother or sister—I send my deepest compassion. May you receive all the support you need, from caring family members and professionals alike. May you find solace, strength, and love as you carry your loss.