When Russia bombed Odessa last year, my sorrow for her people stirred up an old regret: a powerful, long-standing feeling that there, long ago, I disappointed my Grandpa Ben. I was sixteen and my grandfather Benjamin Graham was seventy-three. We were passengers on a cruise ship that sailed from Genoa, Italy, through the Bosphorus Strait into the Black Sea. My grandfather had invited me to join him on the three-week cruise, because the life-partner of his later years—his “beloved Malou”–was off to Uruguay to see her son, and he wanted my company. At the time, though, I was more interested in hanging out with people closer to my own age. On the day our ship docked in Odessa, I slept in and missed the chance have breakfast with Grandpa Ben. Instead, I went ashore with my cruise boyfriend, the bassist in the ship’s rock band, “the Angioletti” (“Little Angels”), leaving my grandfather to visit Odessa alone on the ship’s bus tour.

The Angioletti and me at the Vorontsov Palace, Alupka, 15 kilometers from Yalta

I appear in one photo on my roll of pictures from the cruise. This goofy snapshot of me making lion claws with the Angioletti at the Vorontsov Palace shows that I went ashore without my grandfather at a second Black Sea port: Yalta.

The beach at Yalta, June 1967

I snapped this photo of a lounging stranger and her neighbor at the most crowded beach I’d ever seen in my life, but I never turned my lens on Grandpa. My failure to take a picture of my Grandpa prompts me to ask a deeper question, that can’t be answered with a snapshot. My grandfather and I spent a lot of time together before his death in 1976. Did I ever bring him joy? Last April on a visit to Omaha, Warren Buffett reminded me that “Ben Graham always had a shell around him.” Did I ever break through his shell? Did Grandpa Ben get through my wall of self-absorption? Tender feelings well up, filling my eyes with tears. Under his reserved exterior, did he love me? A child’s longing seizes me, to see his face light up at the sight of me.

Ben Graham, his daughter Marjorie and granddaughter Charlo, near Milford, Connecticut, June 1954

My search for answers leads me to this black and white photo, given to me by my uncle. In the photo, from the summer of 1954, my Grandpa Ben, my mother (Ben’s daughter Marjorie) and me pose at a beach on the Long Island Sound. In this snapshot, Grandpa looks confident and relaxed as he balances me on his upper arm. He does not, however, glow with delight. My mother no doubt conveyed to me that Grandpa was a beloved and trustworthy figure. Still, I look anxious. That’s probably because my own father, uneasy with children, never hoisted me up high. No wonder I clutch Grandpa’s wrist and keep a steadying hand on my mother’s head.

That I might fall from Grandpa Ben’s lofty shoulder wasn’t my only worry. Raised in a family where all of us struggled with issues, each in our own way, I grew up feeling flawed and not good enough. When, twenty years ago, my mother showed me an unpublished poem that Ben Graham wrote at age forty-two, casting himself as a “knight” on a quest “to prove his worth,” I understood that Grandpa Ben had felt deficient, too. What gives me this idea? Well, the knight “bests” his foe and rescues “the maid oppressed,” only to find her (gracious but dismissive) glance has “smote him to the heart.” The maid’s rejection of him proclaims: you’re still not good enough! In his autobiography, Benjamin Graham: Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street, he describes himself in a tone of self-deprecation:

“It early became evident that I was cut out to be a good boy and an excellent scholar, but not much else of consequence.”

Ben Graham’s Memoirs reveal how his drive to prove his worth began in his youth. As a boy, he tried exceedingly hard to be good—a good son, brother, student, and after-school job holder who handed his earnings to his mother. His father, who died when Ben was eight, failed to appreciate him. After the death of the family breadwinner, Ben’s widowed mother helped her sons survive at the edge of poverty, but she fell short on giving them comfort and affection. If only his grandparents could have helped. Alas, Ben’s grandparents lived in England, three thousand miles away. Once when Ben was seven, he and his family sailed from New York to London to visit them, but his grandparents showed little interest in Ben and did nothing to reassure him that he was (to my eyes) adorable.

My search to find out whether I was worthy of love in my Grandpa’s eyes propels me to the moment my grandfather called to invite me on the Black Sea cruise. Aside from my married sister, I was his only grandchild old enough to travel without my parents. Talking on the phone, Grandpa and I shared, not exactly joy, but anticipatory excitement. Neither of us had ever visited our forbidden and scary Cold War adversary—Russia!!

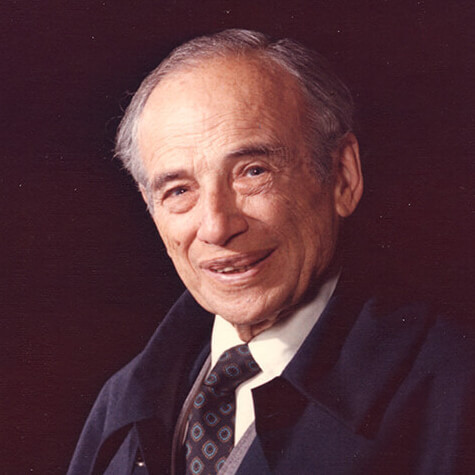

Ben Graham and this granddaughter seated in the cruise ship’s dining room, 1967

My grandfather purchased this poor-quality photo, taken by the ship’s photographer, of the two us dining with our assigned table companions. Our heads are turned away, as if we’re scrutinizing the table’s multiple bottles of San Pellegrino mineral water, con gas, and naturale. Looking back at the cruise, my present-day self feels badly about the choices my younger self made. I slept late, and rarely saw my grandfather until noon. Grandpa didn’t exactly say he missed me at breakfast but he did tell me that my repeated absences fell short of his hopes. We dined together at lunch and dinner, when waiters—liveried like the Duke’s attendants in Rigoletto—brought us plate after plate of delectables. But I’d just become a vegetarian. Disappointment flitted across Grandpa Ben’s face when, once again, I refused one of the chef’s culinary masterpieces. I wasted my grandfather’s money –all that uneaten food!—and I’m still mad at myself for using up all my film on my boyfriend and his fellow band members.

Learn the Morse Code in Ten Minutes, created by Ben Graham for Troop 17 of Beverly Hills, Boy Scouts of America, circa 1960s

I discover that one way to ease feelings of regret is to replace “if only” with “at least.” At least one way I connected with Grandpa was by learning the Morse Code from the sheet that he made for his son’s Boy Scout troop. Grandpa and I joked that if we hit an iceberg, I could radio an SOS.

Instead of reproaching myself over my failings, I’ll describe for you a vivid memory of Grandpa Ben. A slight, trim, balding man with glasses, he would seat himself on a teak steamer chair situated on an upper deck promenade, and open his lined tablet with relish. He told me he was writing “Things I Remember.” Thirty years later, his jottings would be published as Benjamin Graham’s Memoirs. When his pen halted its near-illegible scrawl, he would gaze at the rolling Aegean, his mind ranging back to the last century to conjure a boyhood memory. Rowdy children, raucous laughter, beautiful women—nothing broke his concentration. Yet he would nod if I came near, or reel off a quote from Homer about “Gray-eyed Athena” and “the wine-dark sea.” His love for writing was palpable, and perhaps he imparted that love to me.

Forty-six years after this cruise, Warren Buffett invited me and my husband to Omaha to sort through his nine big Ben Graham file folders, with the goal of selecting papers to donate to an archive of Benjamin Graham papers at Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. An hour into our third day of work at Berkshire Hathaway, my husband touched my arm. His eyes sparkled as he handed me this postcard:

Postcard of Odessa, Rue de Karl Marx, 1960s, or does the photo date from an earlier decade?

Postcard from Ben Graham to Warren & Susie Buffett, sent from Odessa to Omaha, 1967

I turned over the card and saw that Ben Graham had addressed it to “Mr Mrs W S Buffet (sic)” in Omaha, Nebraska. The postmark, in Cyrillic alphabet, displayed “1967”—the year we docked in Odessa!—but I couldn’t read most of what my grandfather wrote. Late that evening, I deciphered his message:

“6/18 Greetings from Russia. I’m on a Black Sea cruise with my granddaughter (just turned 16). She’s the darling of the ship. I’m shining by reflection. Hope you’re all fine. Best from Ben Graham.”

The decades dissolved and I was sixteen again, soaking up Grandpa Ben’s belief that I was the ship’s darling, his granddaughter in whose reflection he shone. Me? The inattentive granddaughter who failed to keep him company on multiple trips ashore? In a flash, I see how harshly I judge my younger self. I remind myself that I grew up feeling unworthy, in part because my father gave me scant attention. It’s understandable that my teenage self needed the affirmation of a boyfriend’s hand-holding. At long last, I’m able to give that sixteen-year-old a break.

The postcard summons up the memory of Grandpa Ben radiating contentment, beaming me his wide smile when I passed him on shipboard. His happy demeanor and his postcard reveal that Ben Graham’s experience of the cruise did not center on my neglect of him. He may have appreciated that I was a self-sufficient girl who made friends and gave him ample time to write.

On his postcard he wrote: “I’m shining by reflection.” He took joy in my presence! His delight in me gives me compassion for my younger self and disperses any lingering “not good enough” cloud cover. I didn’t snap the picture of him I wish I’d taken, but I did create a blog that brings Ben Graham to life. That Ben Graham wrote about me to his thirty-seven-year-old mentee, Warren Buffett, via a postcard from a dark and shadowy Russian seaport—well, I could not be more honored and amazed. It sure seems like Grandpa Ben was boasting about his granddaughter to Warren and his wife Susie.

My grandfather never said he thought I was a “darling.” His postcard from Russia would have stayed in Omaha, if Warren Buffett hadn’t invited me to go through his files. Since Mr. Buffett gave me all his Ben Graham papers to donate to the archive or to do with as I saw fit, I’m free to keep the postcard in my own files. I treasure it as Mr. Buffett’s gift to me.

What can we learn from Ben Graham’s postcard to Warren Buffett? That no one needs to be perfect—that children, parents and, grandparents don’t always have to be attentive in order to be seen as loving and loveable. That expressing delight in a child or grandchild can be a potent force to help them feel good enough. Sheila Kohler, a Psychology Today blogger, posits that the most essential thing a parent can give a child is assurance that their presence gives joy and delight. Describing the message children crave, she writes: “By simply being there in the world, the child is a precious gift. He or she does not have to prove anything, do anything special; does not have to be anything extraordinary, but rather by just being who they are, they bring delight to the parent’s heart.”

My sixteen-year-old self did not hear this message from my grandfather. Perhaps he didn’t show his delight in my presence, or if he did, I couldn’t take it in. Truly, the praiseful message Ben Graham wrote to Mr. and Mrs. Buffett, read posthumously a half century later, means the world to this grandchild. Ben Graham and I, like legions of other children, grew up uncertain about whether we were good enough and worthy of love. With this postcard, the father of value investing teaches us the importance of showing children and grandchildren how much we value them. I only wish that, as a boy, Ben Graham could have gotten what he gave.