Ben Graham’s mother Dorothy died before I was born, so I never had the chance to meet her. I can only get to know my great-grandmother through a scant few family photos, and from Ben Graham’s writings about her in his autobiography, Benjamin Graham: The Memoirs of the Dean of Wall Street. Below, he describes her from the vantage point of himself as a young man:

“My memory is of a stately lady, but actually, she was very small—under five feet—and when she walked the street surrounded by her three grown-up sons, she seemed like something tiny and precious, entrusted to the care of robust guardians.”

As a girl, Dorothy depended on her governesses and parents. As a wife, she relied on her husband. As a widow, she counted on her older brother and her sons, whom she raised to be her “guardians” and providers. Ben adds that she held herself “with dignity and grace,” and that “she retained the delicacy of her features and her fine-china skin up to her sudden death at the age of seventy-six.”

The Most Influential Person in Ben Graham’s Life

Dorothy (nee Gesundheit) Graham (1870-1944) may have been small of stature but she loomed large—as the most influential person in Ben Graham’s life. Ben’s father died when he was eight, leaving Dorothy to bring up Ben and his two older brothers, Leon and Victor. She led the family with a firm hand through the ensuing decade of financial hardship. I want to like and admire her—even love her—as a revered forebear, the mother who helped my grandfather become the Grandpa Ben I knew. But I can’t. Why not? Because on page two of his Memoirs, Ben Graham says she told him that after he was born, her first impulse was to throw him out the window. She already had two sons and wanted her newborn baby to be a daughter. I empathize with her plight—loneliness, exhaustion, her longing for a female ally. But I find myself harshly judging her decision to tell Ben about her excruciating moment of rejection when he was a little boy. I think her words contributed to Ben’s lifelong feeling he wasn’t good enough. That he must be a very good boy who always obeyed her orders, or she might cast him away.

My Quest

The last thing I want to do is disrespect my own great-grandmother, a fellow woman, a Polish Jewish refugee who struggled to raise her family as a single mother in sexist, misogynist, xenophobic New York. I want to hold her in high regard. To feel affection for her, I also want to learn everything I can about Dorothy and Ben’s mother-son relationship.

Perhaps if I consider the challenges and setbacks my great-grandmother faced, my heart will soften toward her. Born in 1870, Dorothy Gesundheit grew up in an affluent Jewish family in Warsaw, Poland, where her father was a well-to-do merchant. I posit that Dorothy was raised not by one, but by two or more governesses who took care of her and her siblings around the clock. It’s probable that Dorothy received little mothering from her own mother.

Dorothy’s grandfather Jacob Gesundheit, Chief Rabbi of Warsaw, circa 1870-1878.

Her mother’s father–Jacob Gesundheit (1815-1878), an esteemed Talmudic scholar and teacher—served for four years in the honored post of chief rabbi of Warsaw, then home to the largest Jewish population in the world. Jacob Gesundheit and his great-grandson Benjamin Graham shared some extraordinary talents; each shone in his own sphere as a writer, teacher and original thinker.

In researching Polish history, I discovered that, in 1881, Dorothy lived through the three days of rioting known as the Warsaw Pogrom. Mobs attacked Jewish businesses and homes and raped Jewish women, shattering the security of the Jewish community. She was eleven years old. What a terrifying experience that must have been. Many families of means left, but Dorothy’s family stayed while she completed high school during the years when Warsaw grew increasingly anti-Semitic.

At eighteen, she emigrated with her parents from Warsaw to England. Dorothy settled in England, met and married Ben’s father Isaac Grossbaum, and bore three sons—only to face a second dislocation at twenty-five, when she and Isaac emigrated from London to New York. There, Isaac’s china shop prospered and the young Grossbaum family enjoyed a few boom years. They owned a private four-story brownstone and employed servants. Then Isaac died suddenly of pancreatic cancer and Dorothy lost everything except her sons. She became a widow at thirty-three, with three children to raise and no means of support. The family lived on handouts from Dorothy’s brother Maurice. She would be short of money for the duration of Ben’s youth.

“Quite a comedown for a lady who not too many years before had been mistress of a large house, with a cook, upstairs maid and French governess.” Ben Graham

All He Had

Eight years old when he lost his father, Ben Graham described his mother as “a lily who needed no gilding.” To gild means to cover with a thin layer of gold. “To gild the lily” means to add adornment to something that is already perfect. She was all he had—his one surviving parent. In psychological terms, she was his primary attachment figure. He depended on her for his physical and emotional survival. She did have many admirable qualities. Foremost, Dorothy stayed by her three sons. After Isaac died and his china shop failed, she lost her house and sold off the family’s belongings. As they slipped into poverty, Dorothy reassured her boys with her steadfast presence.

Dorothy’s being “all he had” also amplified her shortcomings. Ben Graham’s evocation of his mother in the Memoirs is characterized by ambivalence. One minute he praises her for her “toughness, resiliency, and resourcefulness,” and the next minute, he depicts her as selfish and uncaring.

No Cookies For Young Men

“Mother had many virtues, and also a few faults.”

Ben Graham puts “faults” last in the above quote, giving the word more emphasis. One fault emerges when Ben Graham recalls his mother’s love for “dainties,” including “expensive sweet butter.” She made sure the boys were “very careful with the butter.” Yet Dorothy sometimes allotted their entire ration of butter to a batch of home-baked cookies. Ben tells us: “[She] persuaded herself that they were too ethereal for the gross palates of mere boys.” She put the cookies in a tin box that she hid amongst her lingerie in a wardrobe in her bedroom. Ben discovered her cache and would sneak one or two cookies for himself. When his mother caught him in the act, “her reproof was so gentle that I felt all the more ashamed of myself.” Years later, he understood that “Mother’s conscience must have troubled her”—his gentle way of saying she felt guilty for hoarding the cookies for herself. He avoided calling her stingy.

That hidden tin of cookies convinced Ben Graham that his mother, and women overall, were more deserving than boys like him and his brothers. His early experience of his mother’s selfishness may have sparked the mature Ben Graham’s generosity that profoundly touched Warren Buffett.

Reflecting on this passage in the Memoirs, I judge Dorothy for lacking the parental impulse to share treats with her sons. I do have that urge to share with children I hold dear. But sometimes I share her impulse—to save the best for myself. Thankfully I don’t live on the edge of poverty, as she did. I rarely make cookies but I can afford to buy enough organic strawberries and raspberries to have plenty to share with the children I love. Still, I sometimes finish off the most delectable peach, without offering any to my husband, or take the softer slice of bread. Seeing this tendency in myself has tempered my judgements. Rather than deem her self-serving and ungenerous, I see my great-grandmother as stressed by lack of money and agency. I respect that she did a good job staving off hunger and homelessness. How difficult it must have been, to rely year after year on the largess of her volatile brother, Maurice.

I don’t love the picture of Dorothy that emerges from Ben Graham’s Memoirs. But whenever I get the impulse to take the best for myself—and I do!—I feel a pang of connection with her.

The One and Only Time Dorothy Nurtured and Comforted Ben

Toward the end of the Memoirs, in his “Self Portrait at Sixty-Three,” Ben Graham revealed his epiphany that as a boy, he built a “breastwork” around his heart because “those who loved him dearly would so often wound him.” I’m certain that Dorothy was one of those who wounded him. As a little boy, it must have hurt deeply when she told him that she’d wanted to throw him out the window when he was born. What else do the Memoirs reveal about Dorothy’s mothering?

“I received support when I needed it. [This granddaughter disagrees.] Otherwise, I was left to grow strong on my own. For example, on an extremely cold winter’s day I went ice-skating on the Central Park Lake, just below 110th Street. Of course I had walked there and back.

“I recall coming home half-frozen and nearly in tears from the bitter discomfort. Mother helped me off with my wraps, sat me near the fire, chafed my hands to bring back the circulation, and gave me some hot tea to drink. All perfectly normal, you say: what does it prove? But this scene left an indelible impression with me, for it was the only occasion I can remember—except, perhaps, when I was sick in bed—that my mother or anyone else ever showed such solicitude for a minor ailment of mine. In our household, we were supposed to cure our own wounds, unless they were serious, and to complain about practically nothing.”

Ben Graham

My grandfather’s words bruise my heart. How often do I see a beloved child burst into tears and beeline for the nearest parent, seeking a hug and a listening ear? On any given morning, the child might feel upset, get an owie, want a bandaid, recount a nightmare, and need a snack. Each time the parent or grandparent shows caring, the child registers that they are loved. That Dorothy only showed caring for Ben Graham once—once!—when he had a “minor ailment” is just too sad for words. He may have mattered to his mother as a present and future care-taker and wage earner, yet here he admits that he suffered maternal neglect. He lays bare his wounds. He tells us that he felt bereft of love.

Ben Graham Built A Shell

How did this neglectful parenting shape Ben? He tells us that by age twelve:

“I knew how to steel myself against Fortune’s slings and arrows, to earn a little money in a variety of ways, to concentrate hard on whatever I had to do—and, above all, to rely mainly upon myself for understanding, encouragement and pretty near everything else.”

How alone he sounds! He might have done what some kids do to assuage hurt—drink, use drugs, lose hope, quit school, turn bitter, feel shame, choose angry friends. He did none of those things. Instead, he built a protective “breastwork” around his heart. He grew strong and self-sufficient, at the cost of vulnerability and connection.

Hermit crab in shell

On my visit to Omaha, Warren Buffett reminded me that Ben Graham always had a shell around him. Dorothy had her own shell, which helped her to withstand two uprootings, her husband’s death, single motherhood, and a slide from affluence to near-poverty. She compelled her sons to be strong, by withholding comfort and sympathy and expecting them to be self-reliant at an early age. She asked Ben and his brothers to suppress their feelings and needs, to take care of themselves, and to take care of her—by asking nothing, following her orders, and earning money. Her demanding, laissez-faire mothering toughened Ben’s shell.

Ben Graham managed to safeguard his own generous nature within that protective husk, his innate kindness, his friendliness, his determination to accomplish something big and prove his worth. So, too, the sensitive boy who felt not good enough and unworthy, yet who longed to love and be loved, pulsed within that protective shell. He had probably survived by seeing his mother as better than she was, as many children do. Ben saw her as a “lily” and himself as a deficient bud, unworthy of her cookies, her affection, her attention. Not until he was sixty-three did he deem it safe to see his wounds and begin to heal.

Empowered Single Mom

Dorothy raised her sons during the first decade and a half of the 20th century, when women were considered second-class citizens. The 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, would not be ratified until 1920. Unless they could afford to employ servants, most women of her time spent long hours each day cooking, shopping, washing dishes, laundering clothes, cleaning house, and taking care of children. Ben Graham tells us that his mother Dorothy, by contrast, was “averse to work or concentrated effort—unless absolutely necessary.” Ben attests that she “developed quite an art of transferring household chores to her sons.” She was so profoundly shaped by her wealthy upbringing that, even after Isaac’s business failed subsequent to his death, she still thought of herself as an upper-class woman served by other people.

She simply shifted the provider role from her husband and servants to her sons. She went to bed at 1 am and rose at 10 am. Her sons made their own breakfast and got themselves off to school. She never worked outside the home. She likely felt it beneath her to seek employment, say as a sales clerk at Bloomingdales, where she once shopped as a well-to-do wife. She expected her sons to take after-school jobs, and give her their earnings to help make ends meet.

Ben Graham the Grocery Shopper

“We boys didn’t cook dinner, but we dried the dishes, made the beds, pushed the carpet sweeper. I ran most of the errands, which meant that I did most of the shopping.” Ben Graham

Dorothy’s skill at getting Ben to buy the food, and all three boys to do household jobs, impresses me. Have you ever struggled to get your kid to do just one chore—say, taking out the garbage? I have. If Dorothy were living today, she might be a social media star, posting tips for single moms on how to mobilize their kids to clean the house and ready themselves for school. Even if Dorothy simply felt that as an elegant lady, it was not her place to do childcare and chores, I admire the way she defied the sexism of her time. Standing 4’11” tall, she took charge and ruled the house.

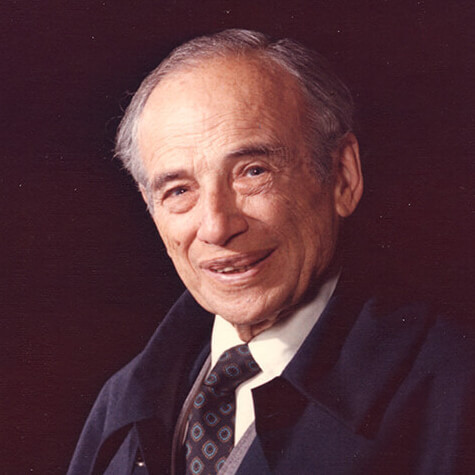

Ben Graham, his mother Dorothy Graham (center), and a friend, 1936

This is the only photograph of my great-grandmother that I find in my mother’s stash. Ben, who holds a small bunch of flowers, leans his head and shoulders toward his mother. Dorothy stands erect, chin set, an imposing presence irrespective of her short stature. Ben Graham the boy shopper grew up to be a man who always brought his mother a bag of groceries when he paid her a visit. Even when he was lonely after his second marriage ended, with no dining partner, and would purchase an extra chop or two, Dorothy never invited him to stay or cooked him a dinner. She cooked only for herself. Still selfish and uncaring, says my judgement. Still remote, and uninterested in spending time with her son. (Three generations later, I’m the opposite.) Once a week Ben would take her out to a restaurant, always paying the bill, just as he paid her rent and gave her a stipend for her living expenses. His job remained to take care of her, never the other way around.

Starting when he could do chores and earn money at age nine, Dorothy let Ben know that she relied on him. She counted on his household help, trusted him to excel as a student, and harbored high hopes for his future earning power. That was her, albeit limited, way of communicating that she saw him as capable and that he mattered to her.

Dorothy’s demand that the boys do most of the housework as well as hold after-school jobs had negative consequences for her sons. Like many kids who work to contribute to the family income, Ben had little time for a social life. In college, he worked such long hours to support himself and his mother that he didn’t make a single friend.

My Debt of Gratitude

In the words of Seymour Chatman, the editor of the Memoirs, “[Doubtless] it was a fortitude like hers that enabled [Ben Graham] to weather both personal and business catastrophes.” Initially, I don’t see many examples of Dorothy’s fortitude. Then I notice that Ben titles Chapter Two of his Memoirs, “Family Tragedies and My Mother’s Perseverance.” Dorothy did persevere in the face of hardship and tragedy, Raised as an upper-class woman, she lost her husband and the grand way of life he provided, lived on handouts from family, and then found herself flat broke after losing her last $5,000 in a bucket shop swindle. After that, she tried and failed at running a boardinghouse. She attempted a second boardinghouse, demonstrating her resilience. When failure struck again, she relied on her own survivor skills. She stayed by her sons and raised my grandfather to be tough of spirit, self-reliant, and resistant to adversity. She taught Ben Graham how to survive.

At last, I appreciate her. I owe my great-grandmother Dorothy a debt of gratitude. I would not have been born if my grandfather hadn’t survived boyhood, or if he’d reached adulthood too broken to marry and have children. Ben, Dorothy, and countless ancestors gave me life. Dorothy taught self-reliance to Ben, and he passed on his determination and fortitude to my mother and me, giving us the capacity to survive and persevere.